To the untutored ear, the Beijing dialect can sound like someone talking with a mouthful of marbles, inspiring numerous parodies and viral videos. Its colorful vocabulary and distinctive pronunciation have inspired traditional performance arts such as cross-talk, a form of comic dialogue, and kuaibanr, storytelling accompanied by bamboo clappers.

But the Beijing dialect is disappearing, a victim of language standardization in schools and offices, urban redevelopment and migration. In 2013, officials and academics in the Chinese capital began a project to record the dialect’s remaining speakers before it fades away completely. The material is to be released to the public as an online museum and interactive database by year’s end.

“You almost never hear the old Beijing dialect on the city streets nowadays,” said Gao Guosen, 68, who has been identified by the city government as a “pure” speaker. “I don’t even speak it anymore with my family members or childhood friends.”

Photo: Reuters/Thomas Peter

The dialect’s most marked characteristic is its habit of adding an “r” to the end of syllables. This, coupled with the frequent “swallowing” of consonants, can give the Beijing vernacular a punchy, jocular feel. For example, buzhidao (不知道), standard Chinese for “I don’t know,” becomes burdao in the Beijing dialect. Laoshi (老師), or teacher, can come out sounding laoer.

In the 1930s, China’s Republican government began defining and promoting a common language for the country, referred to in English as Mandarin, that drew heavily, but far from completely, on the Beijing dialect. The Communist government’s introduction of an official Romanization system in the 1950s reinforced standardized pronunciation for Chinese characters. These measures enhanced communication among Chinese from different regions, but they also diminished the relevance of dialects. A 2010 study by Beijing Union University found that 49 percent of local Beijing residents born after 1980 would rather speak Mandarin than the Beijing dialect, while 85 percent of migrants to Beijing preferred that their children learn Mandarin.

The remaking of the city has also played a role in diluting the language. Into the mid-20th century, much of Beijing’s population lived clustered in the hutongs, or alleyways, that crisscrossed the neighborhoods surrounding the Forbidden City. Today, only a small fraction of an estimated 3,700 hutongs remain, their residents often scattered to apartment complexes on the city’s outskirts. And the city has become a magnet for migrants from other parts of China. According to China’s last national census, an average of about 450,000 people moved to Beijing each year between 2000 and 2010, making about one-third of Beijing’s residents nonlocals.

Gao, a diminutive man with a booming voice, remembers how different it used to be.

“Until this project, I didn’t even know that what I was speaking was a dialect, because everyone around me used to speak like that,” Gao said in his new apartment, not far from the hutong where he lived for more than 60 years.

According to the UN, nearly 100 Chinese dialects, many of them spoken by China’s 55 recognized ethnic minorities, are in danger of dying out. Efforts are also underway in Shanghai, as well as in Jiangsu and five other provinces, to create databases as part of a project under the Ministry of Education to research dialects and cultural practices nationwide.

Yet the potential loss of the Beijing dialect is especially alarming because of the cultural heft it carries.

“As China’s ancient and modern capital, Beijing and thus its linguistic culture as well are representative of our entire nation’s civilization,” said Zhang Shifang, a professor at the Beijing Language and Culture University who oversaw the effort to record native speakers. “For Beijing people themselves, the Beijing dialect is an important symbol of identity.”

The dialect is a testament to the city’s tumultuous history of invasion and foreign rule. The Mongol Empire ruled China in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Manchus, an ethnic group from northeast Asia, ruled from the mid-17th century into the 20th. As a result, the Beijing dialect contains words derived from both Mongolian and Manchurian. The intervening Ming dynasty, which maintained its first capital in Nanjing for several decades before moving to Beijing, introduced southern speech elements.

The dialect varied within the city itself. The historically wealthier neighborhoods north of the Forbidden City spoke with an accent considered more refined than that found in the poorer neighborhoods to the south, home to craftsmen and performers.

For Gao, the vanishing dialect of his youth is nothing to be mourned, although he is happy that more people are paying attention.

“Society needs a unified language and culture to develop,” he said. “If we restored the old things, then the road ahead wouldn’t exist.”

“But I love to listen to the Beijing dialect,” he said. “It is something innate. When I speak the Beijing dialect, it comes naturally from my heart.”

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

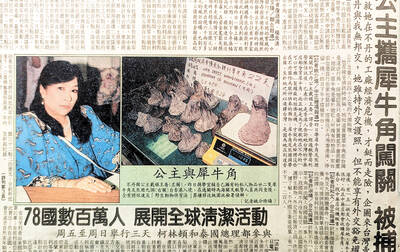

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the