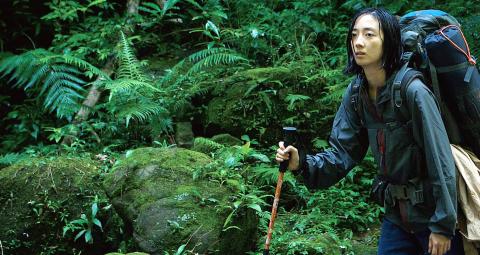

At face value, Foret Debussy is a stunningly shot Taiwanese version of Survivor, featuring mother-and-daughter duo Lu Yi-ching (陸弈靜) and Gwei Lun-mei (桂綸鎂), who are hiding deep in the forest due to a terrible tragedy that tortures them constantly.

Despite the backstory and despair-filled atmosphere, most of the actual sequences focus on them trying to survive and the hardships they face — from trying to fashion a canopy to shelter from the rain to fishing with hand-made rods to ingesting poison berries.

This is the first full-length feature by director Kuo Cheng-chui (郭承衢), who also cast Lu and Gwei as a mother and daughter eight years ago in his short film Family Viewing (闔家觀賞). Kuo calls Foret Debussy a “phytoncide film,” and green is indeed all you will see throughout. The title alludes to how composer Claude Debussy was deeply inspired by nature, and as you can image, his music features prominently in the film.

Photo courtesy of Warner Bros

Gwei plays the wan, silent and tortured persona perfectly, languishing in the past as her mother tries to keep them alive despite her own grief, which does erupt in bursts. The dialogue is sparse, but every sentence counts — we basically find out what happened through aural flashbacks and the few sentences exchanged between the two.

Here’s an example: “Did you ever think about the consequences?” Lu asks Gwei while she tries to unsuccessfully light a fire. After a very long pause, Gwei replies calmly, “You would have done the same.” Then they carry on with their tasks in silence, and finally Lu walks away.

This is a testament to the acting skills of the two protagonists as their sorrow, their complicated feelings toward each other and the suffocating tension surrounding them remain clear and powerful even though nothing significant is actually happening in the film. The otherworldly environment and surrealness of the whole situation also adds to the intrigue.

There also seems to be an environmental protection theme behind the film, but is only directly alluded to in two sequences. Perhaps showing the fact that there are still such pristine and untouched landscapes in Taiwan is enough.

Unfortunately, the story stops halfway through the film. There are no more flashbacks, or any dialogue at all for that matter, as it becomes sort of a vehicle for Gwei to show off her acting chops (which will probably win her some acting awards) and the production team to flaunt their brilliant visuals. It meanders on and on, and all the tension and intrigue that made the first half interesting turns into pure anguish and desperation, and one starts to wonder what is the point of the film and where it is going.

At first, the camera sequences work beautifully with the lush scenery, using a mix of static shots, wide pans and hand-held camera closeups while playing with depth of field to create compelling moods and effects. A memorable sequence takes place when Gwei’s character reminisces of a past conversation while standing with her face very close to a tree. The camera zooms in on her face, then circles the tree in an extreme close-up fashion where we can clearly see the moss, bark and leaves and slowly returns to Gwei’s face from the other side as the memory concludes.

But that was when there was still a story. As the film moves on and the story completely stops, these techniques become vanity flourishes as they lose their connotation. Soon, the endless greenery turns claustrophobic — which is probably the director’s intent, but it could have been handled in a more eventful way. While it is an arthouse film, the way the story is revealed in the first half already departs from the norm enough while still being entertaining. Sometimes you don’t have to go further than that.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an