Taiwan in Time: July 25 to July 31

In late July of 1914, a fierce, two-month battle was nearing its end in the mountains of present-day Hualien County (花蓮).

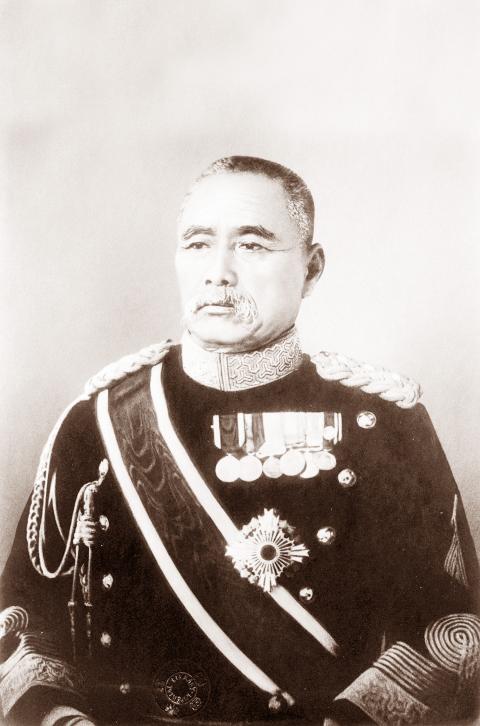

Sakuma Samata, then-governor general of Taiwan who personally participated in the battle, had fallen off a cliff a month earlier and was in critical condition — but the outcome was already decided, as the main resistance had surrendered and given up their weapons a few weeks earlier.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

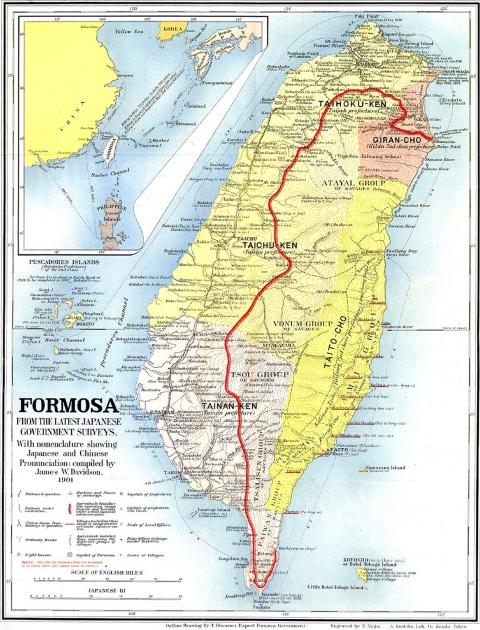

Soon, the Japanese would finally effectively control Taiwan in its entirety, the process taking more than two decades as it spent the first decade dealing with armed Han uprisings.

With more than 10,000 men on the Japanese side, this would be the largest and final battle of Sakuma’s Aboriginal pacification campaign.

The Japanese took over Taiwan in 1895, but up until 1910, they still were not able to entirely control the mountainous Aboriginal areas. The government mostly isolated the Aborigines in the mountains with “guard lines,” which consisted of wooden or electric fences (and sometimes landmines) with guard stations. These lines were originally defensive in nature, but eventually they became a means of cutting off and encircling the tribes as they were built deeper and deeper into Aboriginal territory.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Truku had caused the colonial government trouble as early as 1896 and was reportedly one of the fiercest tribes to resist Japanese rule. The last major incident took place just four months after Sakuma took office in August 1906, when about 30 Japanese were killed, including the governor of Karenko Subprefecture (the eastern part of today’s Hualien County).

Sakuma had dealt with the Aborigines as early as 1874 during the Mudan Incident, when Japan sent a punitive expedition to punish Paiwan tribesmen who had killed 54 shipwrecked Ryukuan sailors. He reportedly earned the epithet “Demon Sakuma” due to his fierceness during this battle and was the one who killed the Mudan Village chief.

In 1907, Sakuma announced his first five-year plan to “govern the savages.” For the Aborigines in the Truku area, this entailed setting up new guard lines in the mountains to further isolate the tribes, and then finally subjugating them through military action if necessary. He also had ships patrol the coast to cut them off from the other side.

Some Aborigines surrendered and allowed the enclosures, either intimidated by force or enticed by governmental promises — but others decided to fight, leading to several bloody incidents. Sakuma decided that a new direction was needed.

In 1910, he received massive funding from the Japanese government for a new five-year plan, taking on a more aggressive, militaristic approach with armed police, especially in the northern part of Taiwan. They continued to push the guard lines forward, with a major goal of confiscating the weapons of the Aborigines, leaving them with no means to resist. Most estimates show that more than 20,000 guns were collected during this time.

There were several groups that were classified as “vicious savages,” and therefore, Sakuma required military expeditions. After campaigns against other tribes in 1910, 1911 and 1913, Sakuma saved the Truku for last.

Starting from 1913, Sakuma sent scouts to survey the Truku terrain, and also trained Truku language translators. In late May of 1914, the 69-year-old personally led more than 10,000 police, soldiers and other personnel toward Truku territory. Most records show that the Truku had at most 3,000 fighting men.

This was not a straight-up extermination campaign, as the troops promised the Aborigines they wouldn’t be harmed if they handed over all their guns and ammunition — and many did so. After two months of battle, the fighting gradually resided and the official surrender ceremony was held on Aug. 13.

At the end of the war, the Japanese had only lost about 150 men, of which 76 were killed in battle, according to official numbers from the Governor-General’s Office. There are no numbers on how many Aborigines were killed.

Afterward, the Japanese sent personnel in to the mountains to build roads and bridges, set up telephone wires as well as round up the remaining ammunition and people who went into hiding. They also built police and patrol facilities and stationed troops in the area.

Sakuma recovered from his injuries and headed back to Japan in September to report to the emperor the completion of his mission. He remained as governor-general until April 1915.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as