Within the imperial chambers of the Wanli Emperor (萬曆), sovereign of the Ming Dynasty from 1563 to 1620, could be found an encyclopedic work of cartographic craftsmanship unlike anything existing in Europe.

It was a multicolored world map mounted on a six-paneled folding screen, taller than a man and twice that in width, which transfixed the emperor with the revelation that his own empire, vast as it was, was nevertheless a minor portion of all under heaven. It was said that the emperor himself frequently studied it with intense curiosity and ordered 12 more full-size copies for the palace.

EXTENT OF THE EMPIRE

Photo courtesy of John J. Tkacik

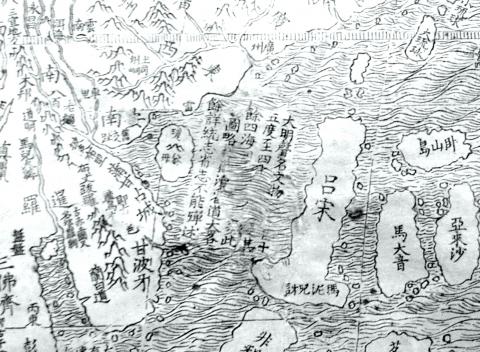

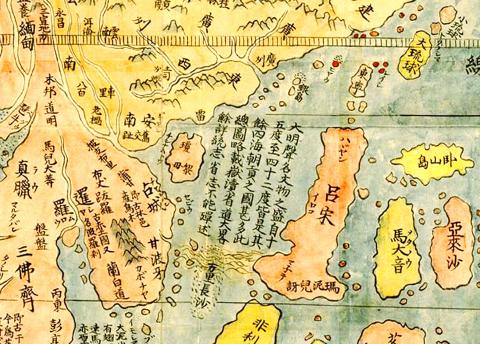

The giant map was entitled Comprehensive Chart of the Myriad Lands upon the Foundation of the Earth (坤輿萬國全圖) and depicted a world 20 times more expansive than the emperor had ever imagined. It bore over 850 place names and minutely scripted legends for each kingdom, island and continent. It featured latitude and longitude lines identifying their locations on the spherical Earth.

In the map quadrant encompassing what we now know as the South China Sea was the legend, “The Great Ming is renowned for the richness of its civilization. It comprises all between the 15th and 42nd parallels. The other tributary realms of the four seas are very numerous.”

During the late Ming, the northern borders of the empire stopped at the 42nd parallel along the Great Wall that protected China from northern tribes. In the south, the empire ended at the Paracel Islands (Xisha Islands, 西沙群島) on the 15th parallel in the South China Sea, beyond which were the Ming vassal kingdoms of Southeast Asia.

Photo courtesy of image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library and Wikimedia Commons

The map was the collaborative work between an Italian Jesuit missionary in Beijing, Matteo Ricci, and a famed Chinese geographer, Li Wocun (李我存). Li compiled the data points for Ming territories, while Ricci filled in the rest of the world and combined European and Chinese geographic knowledge for the first time in Chinese or in any language.

While the Ricci-Li world maps were famous among Ming officials of the era, Ricci was hesitant to present one to the imperial court.

He reported in his Commentary on China that “the [Jesuit] fathers had never given a copy of the map to the [emperor], nor proffered to do so, lest he, seeing China — which according to the Chinese included the greater part of the world — so small, should be offended, thinking that our people had shown it thus in contempt, such, indeed, being the belief of many Chinese men of letters, who made [com]plaint against us, saying that we enlarged our foreign kingdoms, but made China appear small.”

Photo courtesy of image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library and Wikimedia Commons

But such was not the case. Indeed, the emperor was “gratified with the sight of such a fine work, with so many kingdoms and their various strange customs.” Ricci writes that in fact the Emperor “was so pleased with it that he wanted to present a copy of it [on silk] to each of his sons, and other relatives residing in the palace, so that they could hang them up on the walls, by way of pleasant ornamental decoration.”

Ricci reported to the Jesuit Provincial in Macao that “the Fathers were at fault in their fears, because the [emperor] himself, in keeping with his customary good judgment, had no idea that his kingdom would suffer any disparagement by revelation of the truth.”

MODERN ALTERATION?

Ricci’s map is precise documentation that in 1608, Ming sovereignty stretched only as far south as the Paracel Islands. The Spratly Islands (Nansha Islands, 南沙群島) , a chain of rocks, reefs and sandbars known then as the “Long Sandbanks of Ten-thousand Li” (萬里長沙), however, lay yet another 500km beyond Ming waters, south of the 12th parallel.

The map is evidence that China’s current claim that the “[Spratly] Islands have been part of the territory of China since ancient times, and that it has indisputable sovereignty over them and their surrounding maritime areas,” is not so indisputable, after all.

In 2010, when a rare, full-sized original woodblock print of Ricci’s map was on display at the US Library of Congress, I jumped at the chance to view it. I noticed something peculiar.

It seems that, somewhere in its 400-year history, one key feature of this particular map was altered. Part of the legend reading “between the 15th and 42nd parallels” had been erased, with ocean patterns painted over the erasure. A clearer view of the same alteration can be seen on a digital version of the same map on the Web site of the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota, where it is housed.

Whether this is a recent defacement done to obliterate evidence that China’s historical primacy in the South China Sea is a modern fiction, or an ancient one done to eliminate an error, is a subject for further research.

Who made the erasure? The provenance of the University of Minnesota map is not a matter of public record. In 2009, the library procured it from Daniel Crouch, a London-based antiquarian, for about US$1 million. Crouch says that he was fortunate enough to purchase it from a catalog of an auction — in China — from a “private Japanese collector.” That Japanese collector, Crouch said, had owned the map for 35 years, but about six years ago it wound up at auction “in China” where no one seemed to grasp its significance. Whether the map was physically “in China” when the map was auctioned is unclear.

Nonetheless, several other 16th century copies of the Ricci-Li map exist in Europe, South Korea and Japan, and all display the legend intact. A Qing Dynasty copy is at the Royal Geographic Society in London, also intact. Two other hand-drawn versions of the Ricci map are presumed to exist in China, one at the Nanjing Museum and one in the Liaoning Provincial Museum, but neither has been accessible to scholars outside of China for the last 70 years, perhaps because they are evidence of an inconvenient truth that China’s current rulers would rather suppress.

But it is clear evidence that Beijing’s 21st century claims that “the [Spratly] Islands have been part of the territory of China since ancient times” are unsupported in ancient maps owned and studied by China’s emperors themselves. Nor do Beijing’s claims have any foundation in modern international law, least of all in the UN Convention on Law of the Sea to which Beijing is a contracting party. Without a basis in history or law, Beijing’s claims to maritime sovereignty over seas which carry US$5 trillion in international maritime commerce each year now rest solely on brute force.

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that would limit semiconductor

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or