Bi Gan (畢贛) says that growing up in the rural town of Kaili in Guizhou Province, southern China, he did not have a chance of being exposed to arts.

“I used to think paintings were just designs on my T-shirt,” he says.

It is hard to imagine the 26-year-old director’s confessed ignorance, considering his arthouse debut, Kaili Blues (路邊野餐), has excited critics and audiences with its unique aesthetic and sensibility.

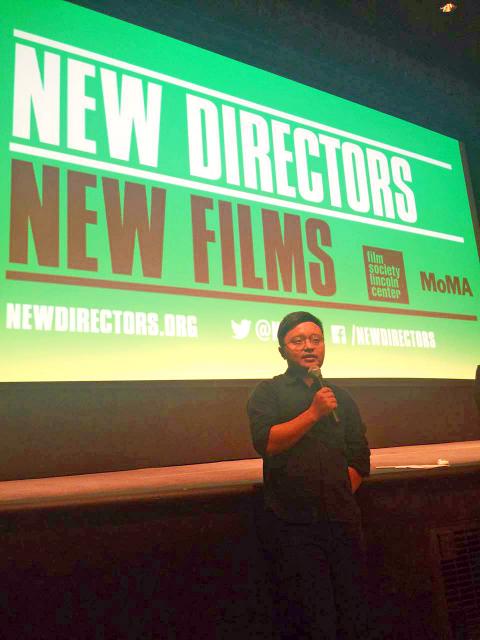

Photo courtesy of Flash Forward Entertainment

The film has toured to more than 40 film festivals and garnered numerous international accolades, including top honors at the Locarno International Film Festival, the Festival of the Three Continents in France and Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards.

Bi, however, did not learn his craft in film schools or hone his skills by working on film sets. His teachers were online movies and pirated DVDs Bi talked his college roommate into buying.

“I know none of the formula in text books to solve problems [when making a film]. I come up with my own solutions. They are basic and raw,” Bi says.

Photo courtesy of Flash Forward Entertainment

SELF-TAUGHT ARTIST

Bi attributes his artistic enlightenment to a copy of Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky’s arthouse masterpiece Stalker he came across at his school’s screening room during his freshman studying broadcasting.

Bi did not know who Tarkovsky was, and after watching the film for a few minutes, decided it was “so horrible” that he needed to study the work thoroughly in order to criticize it.

Photo courtesy of Flash Forward Entertainment

“It was so bad that I could only watch the film for a few minutes a day… On the day I finally finished watching it, I went to the school canteen and suddenly felt a shiver down my spine. I got it, and at that moment, I knew what kind of films I want to make,” Bi says.

It is the kind of film that explores the aesthetic possibility of cinema.

Film critics have correctly noted the aesthetic similarities between Kaili Blues and the movies of Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien (侯孝賢), in particular Goodbye South, Goodbye (南國再見,南國).

“It is a tribute, indicating my cinematic kinship,” Bi says, “It is like Po rejoining his kind in Panda Village [in Kung Fu Panda 3].”

Hou is one of the directors Bi discovered when studying how to make films by watching thousands of movies online and in his dorm room. All the while, he consciously tried to avoid an “official” education.

“At one point, I lived next to the Beijing Film Academy for a few months, but I did not go to one single class. It is not that I do not respect those professors. I had to remind myself that films can be made in whatever way I want,” Bi says.

During college, Bi made Tiger (老虎, 2011) and The Poet and the Singer (金剛經, 2012), both earning recognition at Nanjing’s China Independent Film Festival (中國獨立影像展, CIFF). The two experimental works contain all the elements that are later developed in Kaili Blues.

A PERSONAL CINEMA

Bi has made all his films in and around his hometown of Kaili, using a cast of non-professional actors who are his family and friends. But like Bi’s previous shorts, Kaili Blues is far from a work of social realism.

The story revolves around an ex-con, played by Bi’s uncle-in-law, who now leads an honest life by running a small country clinic and later spends the bulk of the screen time taking on a journey to find his young nephew, Weiwei, played by the director’s half-brother.

The dialogue is sparse in this cinematic cosmos, where dream and reality infiltrate and inform on each other. Yet, central to this mesmerizing, surreal work is a deeply felt motif of memory and a sense of longing to reflect on a past that has disappeared.

Many of the sequences take place in abandoned houses and ruins. Like many towns and small cities in China, Kaili, which is home to the Miao ethnic minority, has undergone rapid urban development in recent years. Concrete buildings are hastily constructed as traditional ways of life fade away.

Bi says he is drawn to the ruins because he wants to capture things before they disappear completely.

CINEMA AS TEMPORAL ART FORM

With Kaili Blues, Bi says he also wants to portray the Chinese way of perceiving time.

“Time is not constant. It can be stretched or condensed. It is not an abstract concept. Rather, this is how we feel and process time,” Bi says.

“Time, to me, is based more on emotion. For example, we are having a great conversation. It feels like we have talked for a long time, but only five minutes have passed. Or when a loved one dies, we are sad, and we feel time,” he adds.

Astonishingly, the director manifests the flow of time with the film’s much talked-about 40 minute-long extended take that follows Chen through rural Guizhou in search of his nephew.

During the protagonist’s journey, the linear notion of time is rendered obsolete. Past, present and future intermingle and conflate as Chen encounters a variety of characters, notably the future version of Weiwei and a woman who could be Chen’s deceased wife.

“It is realistically portrayed, but gives rise to a dreamlike state. To me, it is the most fascinating part of the film,” Bi says.

STAYING CLOSE TO HOME

Contrary to common sense, Bi chooses not to pursue his filmmaking career in big cities where resources are easier to come by and establishing networks with like-minded people easier. He returned home after graduation, got married and his wife recently gave birth.

“In Beijing, I would probably have spent a big chunk of time socializing with people and end up hating film,” Bi says.

“In Kaili, no one asks me about my work or interferes with what I do. I can be more independent… I only want to concentrate on creating films.”

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property