Taiwan in Time: May 16 to May 22

On April 20, 1949, negotiations broke down between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party, as the People’s Liberation Army continued its offensive, capturing the Nationalist capital of Nanjing three days later and then continuing to push southward.

Chen Cheng (陳誠), who had been sent to govern Taiwan five months before the offensive, was worried that Communists would try to sneak their way into Taiwan amid the mass Nationalist retreat across the Taiwan Strait, writes historian Chen Shih-chang (陳世昌) in his book, Taiwanese History, 70 Years After the War (戰後70年台灣史).

Courtesy of Google

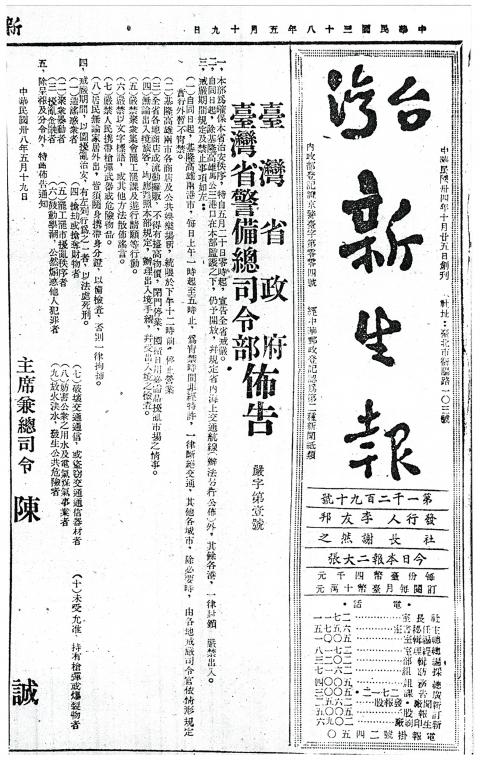

On May 19, Chen Cheng declared martial law, to take effect at midnight the next day.

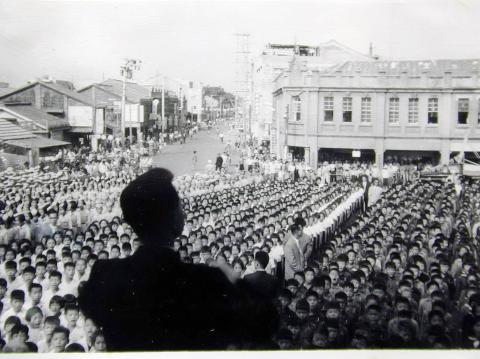

Chen Shih-chang writes in his memoir that martial law provisions made it easier for him to enact laws to restrict people entering and exiting Taiwan — the main purpose being to weed out possible communists. He was likely also responding to unrest within Taiwan, such as the student protests against police brutality that led to the April 6 Incident when military and police personnel stormed National Taiwan Normal University dorms and arrested about 200 students.

Some dispute the legality of this move, claiming that Chen Cheng had no right to declare martial law as, according to Article 39 of the Republic of China constitution, only the president had the power to do so and it had to be subsequently approved by the Legislative Yuan. Chen Cheng, however, claims in his memoir that he was acting under direct orders from the central government.

Photo: Tsai Chih-ming, Taipei Times

No matter what Chen Cheng’s intentions were, or whether it was legal or not, his declaration would remain in place for the next 38 years and 56 days — one of the longest duration of martial law in the modern era.

The real ramifications were that after the KMT’s full retreat to Taiwan, they would use it to keep Taiwan in a constant state of emergency and, combined with other laws, they exercised authoritarian control over the government and people.

It was the second time martial law had been declared in Taiwan. The first one was issued in 1947 by governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) the day the 228 Incident broke out, and curfews were imposed in Taipei and Keelung. Chen lifted it the next day, only to declare it again on March 8 as the situation worsened and government troops clashed with civilians. Meanwhile, the commander in Hsinchu made his own declaration on March 4.

Photo: Wu Hsing-hua, Taipei Times

This period was short-lived. On May 16, Wei Dao-ming (魏道明) arrived to replace Chen Yi, and one of his first acts was to lift martial law and stop the government’s qingxiang (清鄉, the countrywide arresting or killing of civilians suspected to have ties to the uprising).

KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) declared martial law in December 1948 as the civil war worsened — but this issuance excluded non-war zones such as Tibet (which the KMT had no control over anyway), Qinghai and Taiwan.

Chen Cheng’s initial declaration closed all ports except for Keelung, Kaohsiung and Makung, established curfews for civilians and businesses, forbade merchants from raising prices or stocking up on goods for personal use and prohibited public gatherings, strikes, protests, bearing arms and “spreading rumors.” All citizens were required to have identification on them at all times, or face arrest.

Later that month, the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) was enacted, which called for automatic death sentences for internal rebels or traitors to the country. The act specified that all trials be carried out by military tribunals regardless of the subject’s identity. Originally aimed towards Communist collaborators, the KMT would later use the act, along with the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款), to suppress freedom of speech, ban opposition parties and arrest suspected independence activists and other dissidents.

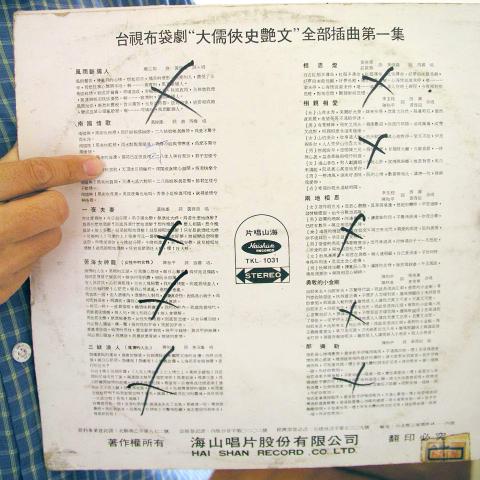

Finally, provisions were enacted allowing government screening and censorship of all publications, recordings and performances. Restrictions included defaming government leaders, promoting communism, swaying civilian loyalty toward government and disrupting social security — but in reality the scope was much wider, including sexually-explicit content and even martial arts novels.

With that, all conditions were ripe for the height of the White Terror era.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)