Taiwan in Time: May 9 to May. 15

In 1874, former Xiamen consul Charles Le Gendre published a pamphlet titled, Is Aboriginal Formosa a Part of the Qing Empire? An Unbiased Statement of the Question.

The topic of interest was timely as it encapsulated much of the international debate before and after the Japanese military expedition to the Hengchun Peninsula (恆春半島 ) in response to the killing of 54 shipwrecked Ryukyuan sailors by Paiwan Aborigines.

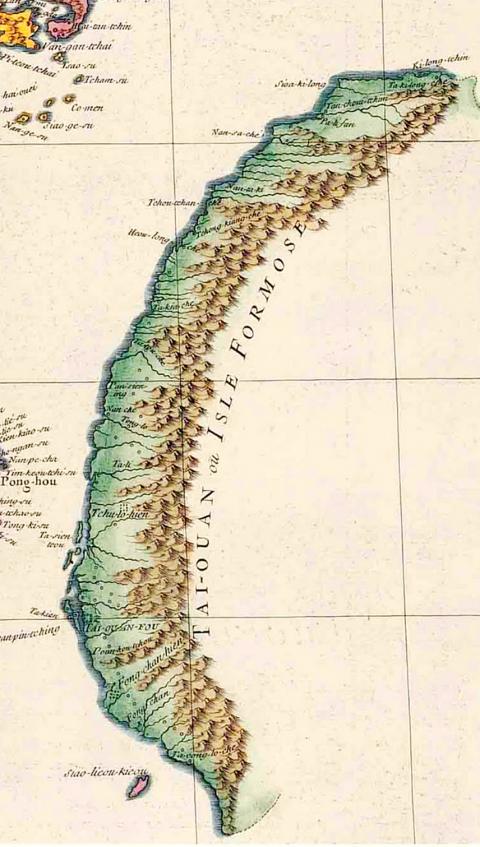

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Le Gendre had negotiated with Aborigines several years prior when they killed several shipwrecked Americans. He later traveled to Japan and became a political consultant who encouraged Japan to colonize the Aboriginal areas of Taiwan, as he considered them to belong to no country.

The military expedition and the resulting conflict, known as the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件), ended with the Qing paying the Japanese to retreat. After the incident, the imperial court, which had long seen Taiwan as a backwater province unworthy of development, started to pay more attention to what was then still part of Fujian Province.

BEYOND REACH

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Historian Wu Mi-cha (吳密察) writes in the preface to The Expedition to Formosa (征臺記事) that the Qing considered Taiwan, in its own words, “beyond the reach of our whip.”

The imperial court restricted cross-strait immigration and forbade settlers from moving into the eastern and southern regions populated by Aborigines as a form of population control, partially in fear of Taiwan becoming a sanctuary for renegades — not unlike the time when anti-Qing leader Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), better known as Koxinga, used it as his base in 1661. Few troops were stationed to prevent a mutiny, Wu writes.

The Qing had always expected unrest to come from within — so it was a surprise when they heard that Japan had attacked, even though the troops landed on the Hengchun Peninsula, one of the Aboriginal areas.

Historian Lin Cheng-jung (林呈蓉) writes in her book, The Truth Behind the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件的真相) that one required a separate passport — which curiously had to be obtained through the British consulate in Kaohsiung or Tainan — to enter such areas. The passport clearly stated that the region was outside of government jurisdiction.

Although Japanese troops landed on Taiwan on May 2, 1874, the Qing did not formally respond until May 11, when it released a statement requesting the Japanese to withdraw its troops, claiming that Japan had violated the Sino-Japanese Friendship and Trade Treaty, signed only three years previously.

On May 23, a ship carrying a Qing official arrived, demanding that the Japanese withdraw. Lin writes that the official did not even disembark, delivering the message and heading back to China — a telling sign the the empire was in decline, as it could not even send an army to deal with the fewer than 3,000 Japanese soldiers suffering from various tropical diseases.

OUT OF THE BACKWATERS

It was not until the Japanese and the Aborigines had already fought their battles and were in peace talks that Shen Baozhen (沈葆楨), China’s minister of naval affairs, arrived on June 21.

Lin writes that Shen not only did not protest Japan’s behavior, but stated his regret in “not being able to aid in the punishment of the Aborigine perpetrators.” In the prefectural capital of Tainan, Qing officials posted public notices stating that the government had obtained word from Japan that no more locals would be harmed, creating the false impression that they were in charge.

Imperial policy on Taiwan changed due to this event, realizing that passive governance would only lead to similar incidents and further questioning of its authority. China finally started developing the territory it had claimed since 1683.

Shen spent about a year in Taiwan after the incident as imperial commissioner. He commissioned Western-style fortifications in Tainan, including the Eternal Golden Castle fortress (億載金城), hired Western experts to help train soldiers, experiment with mechanical coal mining and install electricity, and he sent naval students to study in Europe.

First of all, per Shen’s suggestion, the government lifted the immigration restrictions and the ban on entering Aboriginal areas, and in fact even encouraged it. To “open up” and pacify (often by force) the Aboriginal mountain areas, three major roads were built in the north, central and south. Shen also changed the administrative structure of Taiwan.

To prevent more shipwrecks, the Qing — partly under international pressure — commissioned the construction of the Oluanpi Lighthouse (鵝鑾鼻燈塔) at the southernmost point of Taiwan a year later. Shen also divided Taiwan into smaller administrative regions, and Taipei Prefecture was born during this time.

Despite the Qing’s efforts, Taiwan was invaded again a decade later when the Sino-French war spilled across the strait.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand