Taiwan in Time: March 27 to April 3

What do photographer Chang Tsai (張才), artist Hung Jui-lin (洪瑞麟) and politician Chen Ping-chun (陳炳俊) have in common?

Chang, one of Taiwan’s first documentary photographers, took a series of photos of the divine pig ceremony in New Taipei City’s Sansia District (三峽) in the late 1940s. In the background was the Zushi Temple (祖師廟), which was then being renovated under the supervision of renowned painter and local politician Lee Mei-shu (李梅樹), who would later paint a scene of the ceremony in 1962.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Before he went into politics, Chen was Lee’s elementary school teacher at today’s Sansia Elementary School, and years later, as director of the Zushi Temple, he was instrumental in facilitating Lee’s renovation project.

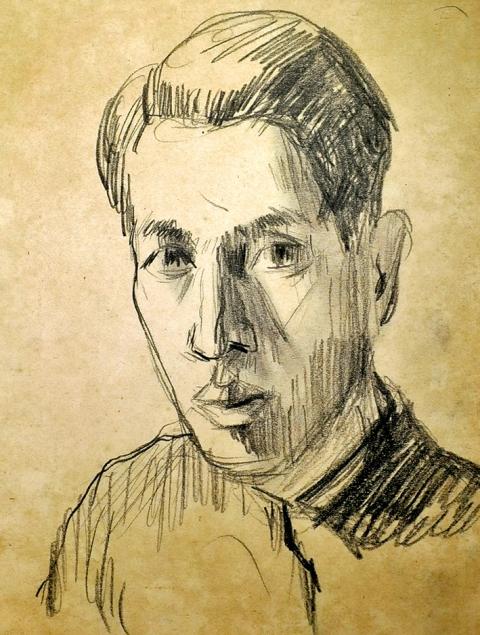

Chen also founded the Chengfu Coal Mine (成福煤礦) in Sansia, which turns 100 this year. Hung, known for his vivid sketches of life in coal mines around Taiwan, studied at Tokyo University of the Arts with Lee, who made several portraits of Hung during that time.

All signs point to Lee, Sansia’s favorite son who would have celebrated his 114th birthday on March 12. Chang, Chen, Hung and many more artists and historic figures somehow connected to Lee are featured in the district’s Lee Mei-shu Month (李梅樹月) exhibition held all over town including the Chengfu mines, where Hung’s work is displayed along with other coal mine-related pieces. Through these connections, we get a sense of Lee’s life and legacy in Sansia.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

LIFE OF A MASTER

Born in 1902 to a wealthy family, Lee’s father objected to his artistic aspirations, and he became a schoolteacher instead. However, Lee never stopped painting, and after his work made it into the Taiwan Art Exhibition (台灣美術展覽會) for the second year in a row, his elder brother defied family wishes and paid for Lee to study at Tokyo University of the Arts.

Chen and Lee would work together as Sansia politicians after World War II — Chen as town mayor and Lee as a Taipei County councilor — and both are recognized for their contributions to local development. Along with local physician Liu Chu-chuan (劉鉅篆), the three are known as the “three immortals (三仙) of Sansia.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The exhibition’s magenta flags can be seen outside the Sansia Presbyterian Church, located near the entrance to Sansia Old Street. Built in 1952, it is featured in several of Lee’s paintings. The guest artist here is Tu Fu-an (杜福安), author of the comic book Love and Devotion: The Story of Mackay (愛與奉獻: 馬偕的故事).

Canadian Presbyterian missionary George Leslie Mackay visited Sansia in 1873, but was met with resistance by locals and was not able to establish a mission until 1876. Tu’s artwork mainly depicts the story of Mackay in Sansia, but also includes a scene telling the story of Lee’s role during the aftermath of the 228 Incident in 1947.

As government troops clashed with civilians around the country during the brutal suppression of the uprising, angry locals gathered in Sansia’s town hall, preparing to join the fight in Taipei.

As chairman of the Sansia town council, Lee reportedly insisted that the townspeople stay calm and refrain from acting rashly. As a result, Sansia was spared from government retaliation and nobody was hurt.

More magenta flags can be seen while walking down Sansia Old Street, which also turns 100 this year. At the end is the Zushi Temple, Lee’s masterpiece.

Built in 1767, the temple was revived after an earthquake in 1833 and again in 1899 after the Japanese burnt it after Taiwan became a colony in 1895.

When many locals returned safely after fighting for Japan during World War II, the townspeople wanted to renovate the temple again to thank the deities for protecting their sons.

Lee was originally reluctant to take on such a momentous task. But legend has it that one day, as he was walking past the temple, a sudden gust of wind blew a favorable divine lot to his feet. As a pious worshipper, he saw this as a sign and took on the job, which became a lifelong project, continuing even after he died in 1983.

It is said that he personally traveled with temple personnel to raise funds, and visited the site every day to oversee construction, meticulously designing the intricate wood, stone and copper carvings and decorations that earned the temple its nickname of “The Eastern Palace of Art.”

Lee never took a penny for his contributions, but he insisted that everything be done right, even if it meant slow progress. By the time of his death, he even had the third or fourth generations of the original craftsmen working for him. Even until this day, it is considered unfinished.

But that’s the way Lee wanted it. Referring to the construction of the St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, which took 120 years, Lee once said: “If we want to build a temple that is representative of our religion, 20-something years really is not that long.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.