Vandy Rattana does not want to be known as an artist who produces “stereotypical” images of Cambodia — genocide, the Khmer Rouge or Angkor Wat — he wants to and succeeds in creating art that exudes great pride in being Cambodian.

“I was inspired by this evil,” Rattana says of the genocide, as his film Monologue screens in the background at The Cube Project Space, where his current solo exhibition, Working-Through: Vandy Rattana and His Ditched Footages, is being held.

The artist, who has been living in Taipei for the past three years, has spent much of his time pouring over literature, poetry and philosophical texts, a habit which he picked up when he moved to France in 2009.

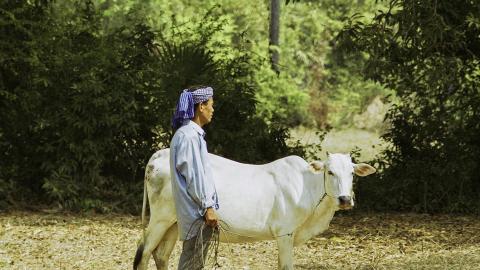

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

“This poetic point of view helps me to interpret the world better than a logical perspective would, since what happened in Cambodia was illogical,” says Rattana.

This influence has played out in his artwork. Monologue started as a poem he wrote for his sister who he never met. She was murdered by the Khmer Rouge in 1978, two years before he was born and a year before the genocide ended.

Monologue, which centers on her burial place — a mass grave which has since been turned into a rice field — is lyrical and lulling. There are no images of skulls or re-enactments of violence. The narrator (Rattana) tells his sister about the world he lives in, the mango trees that grow in their Phnom Penh house or how it’s human nature to “kill one another” and that we “will never move past that stage.”

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

The tone is loving and protective, but also matter-of-fact.

Rattana says his motive is not to judge.

“I don’t want to say, ‘he’s wrong, or he’s right.’ I just want to understand,” the artist tells me.

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

HISTORY AS AN INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY

The journey towards understanding began in 2008. Rattana was living with local farmers in Cambodia’s Kampong Cham Province, photographing rubber plantations for a project when he noticed a couple of very large ponds that were teeming with fish. One day a young villager mentioned to Rattana that they were craters created by bombs dropped by American B-52 bombers during the Vietnam War.

“I felt cheated of not knowing this piece of Cambodian history,” Rattana says.

Photo courtesy of Vandy Rattana

Obsessed with these “bomb ponds,” he traveled around Cambodia searching and photographing them. It was not an easy task since there was not much written by historians in English or Khmer about Operation Menu, the covert American bombing of Cambodia and Laos from 1969 to 1970.

Rattana’s Bomb Ponds series, is, in a sense, revisionist history. It’s hard to tell at first glance what is in the frame. Many of the pictures look like idyllic countryside shots. Throughout the process, people told him to use a bird’s eye perspective to photograph the craters, most of which are 15 meters wide. But he insisted on capturing the point of view as seen by ordinary people who pass by the bomb ponds every day.

“You look at the photograph and think, ‘what a beautiful pond.’ Then you read the caption and you realize that it’s actually a crater and that a bomb created that crater. Your whole perspective changes,” Rattana says.

Though critical of the Cambodian education system, Rattana is glad that it spurred him to find out more information about the past (often via Google and YouTube, he jokes), and by doing so, it felt like he was reclaiming parts of his identity which was taken from him.

“In Cambodia, history learning is an individual responsibility,” he says.

TRAUMA ILLUMINATED BY BEAUTY

Rattana’s photographs do not look like they were taken in 2009. There is a stillness and graininess to them that makes the scenes he captures seem vintage and nostalgic.

The decision to photograph Bomb Ponds with an analog camera was a conscious one, although Rattana now shoots digital, mostly to save time and cost.

“With digital cameras, it’s like you’re eating fast food,” Rattana says.

Everyone may be taking pictures, he says, but are concentrating less on their subject matter. Analog cameras by their very nature, Rattana says, exert greater demands on the photographer, whereas digital cameras have made it easy to lose focus because there is a practically unlimited number of photos that can be shot.

The photographs are raw, grainy and un-embellished for the simple reason that Rattana does not believe in filters, cropping or a lot of editing.

“Other people have the freedom to do that, but it doesn’t seem freeing to me,” he says.

Too much editing would have detracted from the simple message of remembrance and healing. While reading history, Rattana started to question why it was narrated in a depressing way. The photographs in the Bomb Ponds series are not sad per se, but more contemplative, and perhaps a little fatalistic.

Rattana says he wanted to highlight “beauty illuminated by trauma,” and show the various faces of humanity, from the people who dropped the bombs to the historian-photographer (himself) documenting and trying to make sense of it. Rattana does not condemn acts of brutality, though. Rather, he sees it as a sad but integral part of human nature.

“War is just like sex,” he says. “People will keep on doing it until the end of the human race.”

Today, many of the bomb ponds have been filled with new dirt for farmers to grow rice and other crops. The landscape is always changing, and it’s almost as if the photographs are saying, this is what it looks like now, but it might look different in a few years. What history has taught us is that change, good or bad, is inevitable and the onus is on us to remember and move on.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the