Hot on the heels of the success of his debut novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon, American author Vern Sneider spent the summer of 1952 in Taiwan researching his next book.

Ushered in by the 228 Incident of 1947, the White Terror era was at its most brutal at that time as thousands of suspected political dissidents were imprisoned or executed by the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

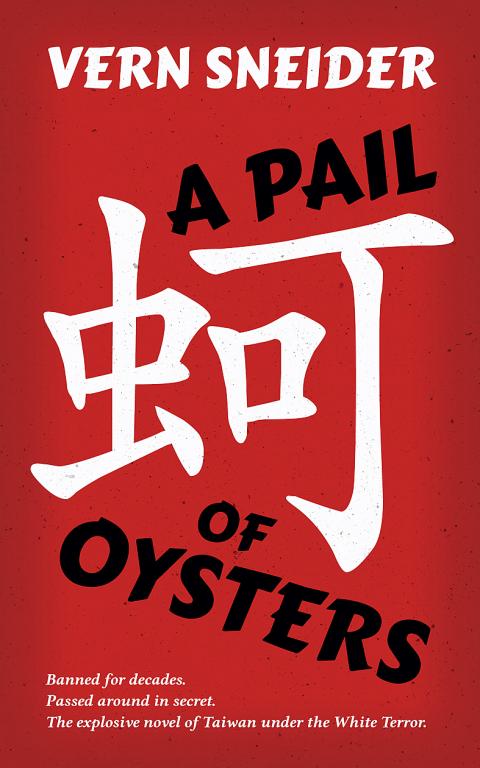

The resulting book, A Pail of Oysters, was banned in Taiwan, but to Sneider’s dismay, even the US denounced it. It was the McCarthy era, and anything portraying the KMT in a negative light was inevitably painted as pro-communist. It went out of print shortly after.

Photo courtesy of camphor press

While Mandarin and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) translations have been available since 2003, English editions are rare (rumor has it that pro-KMT students hunted down and destroyed copies from US libraries), with Abebooks.com just listing six copies, ranging from about NT$900 to NT$3,800.

“It’s one of those books that were passed around in secret during the bad old days,” Taiwan and UK-based Camphor Press cofounder Mark Swofford says.

Camphor Press is today releasing the first republishing of the book since the 1950s in digital format, with a print edition to come soon.

“It was suppressed and never got a fair hearing. We want to give it one,” Swofford says.

The book depicts life during White Terror through a variety of characters — most prominently Li Liu, a half-Hakka and half-Aborigine whose family is robbed by KMT soldiers at the beginning of the novel.

But bashing the KMT isn’t the point of the novel, Swofford says.

“It’s a very complex novel, [written] when many people thought it was just the communists versus the KMT,” he says. “It was more of a middle way sort of thing; from the standpoint of the Taiwanese people.”

RE-INTRODUCTION

Late last year, Jonathan Benda, a lecturer at Boston’s Northeastern University, found himself interviewing Sneider’s 85-year-old widow, June.

Benda was familiar with A Pail of Oysters. He read it during his 18-year stay in Taiwan and published an academic paper on it in 2007. Benda says he had once considered republishing it, but lacked the means to do so — and was surprised when Camphor Press asked him to write the introduction to their new edition.

Benda was eager to learn more about the book. In addition to speaking to June, he also dug up old articles and correspondences and obtained copies of the author’s notes through his hometown museum in Monroe, Michigan.

Stationed in Okinawa and Korea, Sneider had never been to Taiwan before the summer of 1952, but the US Army had him study the country at Princeton University in preparation for possible military occupation during the war.

Benda was impressed with the amount of research Sneider’s notes contained — including interviews with people ranging from then-governor K.C. Wu (吳國楨) to pedicab operators and extensive notes on items such as how children are named and blind masseuses. He even had his palm read, which is featured in the novel.

“It’s easy to point out mistakes or problems with his depictions … but I come away thinking that he got a lot of it right,” Benda says.

Through examining letters, Benda found that Sneider had hoped to counter the pervading pro-KMT perception of Taiwan as “Free China” and show how its people were actually suffering under martial law.

“My viewpoint will be strictly that of the Formosan people, trying to exist under that government,” he wrote to George H. Kerr, author of Formosa Betrayed. “And … maybe, in my small way, I can do something for the people of Formosa.”

But although Sneider was critical of the government, he generally gives a balanced picture, including democracy proponents in the KMT and sympathetic soldiers, Benda says.

In addition, the American perspective is shown through the eyes of Ralph Barton, a journalist investigating life in Taiwan under martial law — which corresponds to Sneider’s role, except that the author believed that fiction is a more powerful vehicle through its “emotional pull,” as detailed in his letter to Kerr.

Sneider died in 1981 — too early for any chance to redeem his book, but at least June is able to see it happen.

“She was glad to have this out during her lifetime,” Swofford says.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of