If, and how, to survive after your founder dies or retires is a major question that dance companies around the world have struggled with, and continue to do so, with varying degrees of success.

It is a question that faced Yang Wan-rung (楊宛蓉) after her husband and cofounder of the Taipei Dance Circle (光環舞集), Liou Shaw-lu (劉紹爐), died on Sept. 1 last year at the age of 65 after the reoccurrence of a brain tumor.

His death came just weeks before the scheduled premiere of Chakra Dances (舞輪脈), which Liou had created to mark the company’s 30th anniversary. The company went ahead with the performances at the Experimental Theater in Taipei, and the rest of the tour, but the question of the company’s future was on the minds of company and audience members alike.

Photo Courtesy of Li Ming-shiun

For while Liou and Yang had founded the troupe together — when they were still dancers with Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) — she was the backbone of the company, handing the administrative and logistics, while Liou was the artistic director and choreographer — and a key performer in the shows almost to the last.

His works, especially the baby-oil series that became the company’s signature, were the result of his years-long pursuit of frictionless movement, breathing techniques and experiments with vocalization, and quite unlike anything else being done in Taiwan or the rest of the world.

However, Liou had said he wanted the company to go on, and so Yang made the decision to produce a new show this year, one that would both honor her husband and mark a new starting point for the troupe.

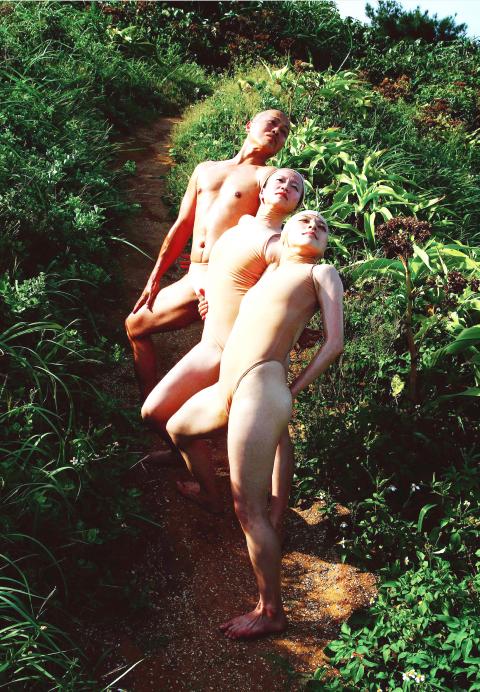

Photo Courtesy of Taipei Dance Circle

She asked three friends — two Taiwanese choreographers and a Dutch “sound explorer and performance artist” — to create new works: Yu Cheng-chieh (余承婕), an associate professor at University of California, Los Angeles; Su Wen-chi (蘇文琪), the founder of YiLab (一當代舞團), who divides her time between Taiwan and London; and Taoyuan-based Mark van Tongeren, who earned a masters’ in ethnomusicology and a doctorate in artistic research, and focuses on overtone singing and theater performance.

The 90-minute show, Lending Ear to Dance, Eye to Sound (聽舞觀聲), opens at the Experimental Theater on Thursday for five shows and then moves to the Hsinchu Municipal Performance Hall for one performance at Sept. 16.

The three works focus on different elements of Liou’s baby oil dances. Yu’s piece, Submerge/Emerge, a documentary-based exploration of Liou’s work, opens the show, followed by Su’s Requiem, which centers on memories of Liou and his dancers, while van Tongeren’s Raw Impulse focuses on the creation of sounds and the body and ties into Liou’s exploration of voices live onstage.

I caught up with Yu, another Cloud Gate alumnus, on Friday last week to talk about her work on the show and her decades-long friendship with Liou and Yang.

“When Shaw-lu established his company, I was a dance student ... we all looked up to him… he was at New York University about the same time as I was [they both studied at the Tisch School of the Arts]. He was always an inspiration, his dedication, his persistence in studying inspired me,” she said, adding that she would frequently see him outside of school at two or three dance events a week, which were just a fraction of the shows he saw.

They stayed in touch after Liou returned to Taiwan, and Yu stayed in the US to dance with several choreographers, including Jose Limon, Gus Solomons and Bebe Miller, before becoming a choreographer herself and turning to academia. He often asked her to teach classes to his dancers whenever she was back on a visit to her family or for performances of her work.

Yu said she had very fond memories of the family ambiance of the company’s old basement studio in Sanchong (三重) in what is now New Taipei City, where the smell of baby oil permeated the air and just-washed costumes were hung in the tiny bathroom to dry.

“I was just back from New York when the 1999 Earthquake happened. There was no electricity, so we set up a ring of candles to do the class. It was so romantic — and we thought were changing the world,” she said.

“I missed his memorial in September [last year], but came back in time to catch the last performance [of Chakra Dances]. Wan-rung said Shaw-lu wanted to continue — he told her to ‘just follow his course.’ I really admired her drive, her desire to continue, and I told her: ‘You should do a show as tribute to Shaw-lu.’ She said: ‘Can you do a piece?’ and I had to say yes,” Yu said.

Saying she felt very honored to be the first “non-baby oil” person asked to choreograph for the company, Yu said the process had been a tremendous challenge, trying to find the nuances and the vocabulary of Liou’s technique.

She said she was helped by her own study of Baguazhang (八卦掌), which began as a form of Taoist meditation and became one of the fiercest of the Chinese martial arts, and which Yu has incorporated for many years in her choreography.

“Baguazhang is about ‘mudwalking,’ or walking on an unpredictable surface, about body to body, body to ground, skin to skin contact,” she said, which provided similarities to Liou’s body-oil moves.

“My work usually follows a documentary approach, so in June, with filmmaker Marianne [Kim], I followed the company on tour to several locations to see how they prepare, how they clean up. The dancers are involved in everything, taping the floors, the walls, preparing to perform. The audience doesn’t get to see that part, Yu said. “I wanted to bring this part up to the surface, to show that the shows are only the tip of the iceberg.”

When I asked how long Submerge/Emerge is, Yu laughed and said the “work” is 30 minutes, but it actually begins with a film that will be shown as the audience is taking their seats.

“It’s a loop, 20 minutes. People can come in, go out,” she said. “Then there is the simultaneous choreography and documentary and then a post-show documentary of dancers cleaning up.”

Lending Ear to Dance, Eye to Sound promises to be both as though-provoking and engaging as Liou’s own choreography and as spirited as the man himself.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an