The first gun I shot was a .22 long rifle outside a friend’s cabin in Copemish, Michigan. A beginner’s gun. Terrified by the thought that I was holding in my hand a machine that was designed to kill people, I repeated my friend’s instructions over and over in my head — lean my right shoulder blade into the butt of the rifle, position my left foot in front of my right foot, squint my left eye, focus my right eye on the target, rest my right index finger on the trigger.

Bang! Once the bullet left the barrel, my fear was suddenly replaced by elation. It didn’t matter that I was way off target — I had just shot a rifle.

Ever since that day a few years ago, I’ve been hooked. While I’m far from being a sharp shooter, I’m addicted to the feeling I get when my finger pulls the trigger, unleashing a torpedoing bullet along with a deafening noise that makes my heart skip a beat.

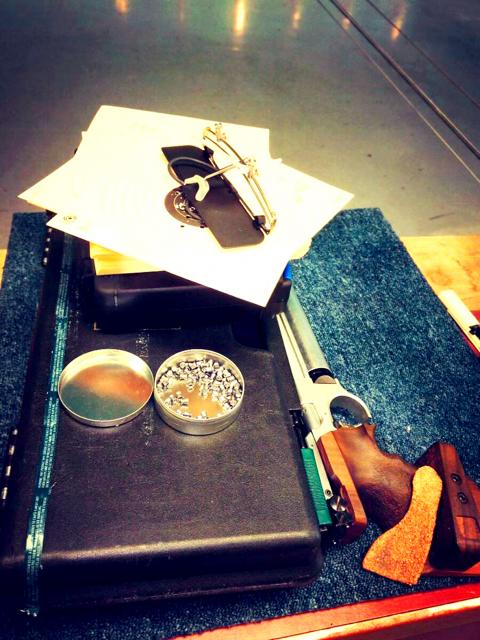

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

While recreational shooting — whether it’s practicing for competitions, game hunting or simply firing at targets for the sake of it — is commonplace in the US, such is not the case in Taiwan because of stricter gun control laws. So you can imagine my excitement when I found out that the Taipei Zhongzheng Sports Center (台北市中正運動中心) near Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall had a 10m shooting range on the sixth floor.

FUN WITH (AIR) GUNS

The first letdown came when I was told beforehand that the shooting range used air guns, not real guns. Convincing myself that it would still be cool, I went anyways. The second letdown was when I stepped inside the shooting range. Nearly everyone was below the age of 18. The air rifles resembled water guns more than they did real guns. The pellets looked more like pins than bullets. A toddler wedged herself between my legs and the wooden ledge where the air guns were poised and scampered across a row of teenagers aiming their air pistols at paper targets.

Photo courtesy of Luo Hsiao-fang

Firing an air rifle felt nothing like firing a real rifle. There’s no loud noise, hence no need for earmuffs, and no recoil, which means no sense of bewilderment that you just fired a gun. A middle-aged man who appeared to be a coach approached me and complimented my stance. Trying to hide my disappointment, I told him I’ve shot real guns before. I learned that the students are part of the Taipei Shooting Sports Association (台北市體育總會射擊協會) and the man, Hsieh Chien-hua (謝建華), is the head coach.

The Taipei City government opened the indoor shooting range as a target practice venue for air gun shooting competitions. Due to Taiwan’s strict gun control laws, there are very few places where civilians can fire real guns. The outdoor clay shooting ranges in Linkou (林口) and Kenting (墾丁) are two popular ones.

“Taiwan’s gun control laws are put in place for good measure,” Hsieh says, adding that even air guns could seriously injure people if they are not handled properly.

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

He adds that “it’s important to cultivate a culture where children learn about safety.”

I glance around and notice that the students are scribbling in their workbooks in between shots. Their textbooks look heavier than the air guns.

“Air gun shooting is all about concentration,” Hsieh tells me. “It’s a skill which will benefit the children in other areas of life too.”

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

SHARP-SHOOTING KIDS

His students, who all hail from different high schools and have been shooting for at least three years, are extremely dedicated. One of them, Chen Shi-heng (陳士亨) says he’s at the shooting range six times a week, from Tuesday to Sunday (the sports center is closed on Mondays).

Although they joke around and peer at each other’s workbooks during their breaks, when it’s time to shoot, the students are dead serious. Donning blinders to block out peripheral distractions, they hold their air pistols steady with their right hands, while their left hands rest snugly in their pockets. Looking dead straight at their targets, they release their triggers almost simultaneously.

Photo courtesy of Luo Hsiao-fang

Unable to contain myself any longer, I ask the students if they think firing a real gun will be cooler than an air gun. They stare at me blankly, unable to fathom my excitement when I recount my experience shooting an M-16 in Vietnam.

“I don’t see a difference with using a real gun and an air gun,” Chen says. “The techniques are similar and I think the feeling that I would get from firing a real gun wouldn’t be too different.”

Another student, Su Pin-chia (蘇品嘉) chimes in. “It’ll be cool if I could use a real gun for target practice one day, but it’s not a big deal if I don’t have one right now.”

Haven’t they ever watched Rambo, Lethal Weapon or just about any cowboy or action movie, I ask.

“We didn’t really grow up watching those kinds of movies,” Chen says, half-laughing at me, as if to say that a pop culture that glamorizes the use of guns was silly.

Apparently, it’s about putting a pellet through a sheet of paper, not blowing up bad guys. Such a sport requires precision and concentration, leaving no room for rash behavior.

Lee Yu-cheng (李祐呈), an older student who’s competed in air gun competitions overseas, agrees with the other two. Yet despite his love for the sport, Li adds that “for now, air gun shooting is somewhat of a hobby.”

He says that the plan is to have a “real job” when he grows up, but to still come to the shooting range for regular target practice.

Kudos to them, but I’m planning for my next rendezvous to be with a real rifle in Linkou or Kenting.

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

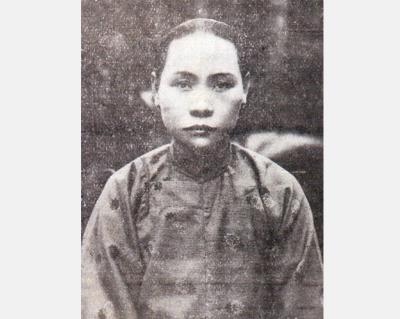

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but