Ying Liang (應亮) has lived in exile ever since he made a film that negatively portrayed China’s legal system. Completed in Hong Kong in 2012 — where the Chinese independent filmmaker has remained — When Night Falls (我還有話要說) is based on the true story of a young man convicted and executed for fatally stabbing six police officers.

Even before the film was released, Ying was threatened with arrest, his family was interrogated and a failed attempt was reportedly made by Chinese authorities to purchase (read: suppress) the film when it premiered at the Jeongju Film Festival in South Korea, which commissioned the work.

That same year, the Chinese government shut down the Chongqing Independent Film and Video Festival (重慶民間映畫交流展), an annual event Ying co-founded in 2007.

Photo Courtesy of Taiwan International Documentary Festival

“My name is closely linked to the festival. No one dares to work with us,” Ying says.

GOVERNMENT CRACKDOWN

Ying’s now-defunct independent film festival is one of several in China that have become targets of a widespread government crackdown on freedom of speech in recent years. While no stranger to official interference, the Beijing Independent Film Festival (北京獨立影像展, BIFF), a prominent platform for Chinese cinema held in Songzhuang (宋莊), an artist commune in the city’s outskirts, was all but shut down in 2012 by the presence of police and a power outrage.

Photo Courtesy of Taiwan International Documentary Festival

The clampdown on BIFF intensified last year as organizers, including artistic director Wang Hongwei (王宏偉), were forced to cancel the event after being detained by police. Meanwhile, the government has confiscated some 1,500 films and countless files, documents and other materials collected over a decade by BIFF sponsor Li Xianting Film Fund (栗憲庭電影基金).

The government also canceled Nanjing’s China Independent Film Festival (中國獨立影像展, CIFF) in 2012, and a year later shut down the Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival (雲之南紀錄影像展), a biennial event held in the southern city of Kunming since 2003.

Indie film festivals in China often serve as venues to shed light on issues ignored by state-controlled media. But they often fall victim to government repression — which has significantly increased since Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) took office in 2012 — due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter.

Photo Courtesy of Taiwan International Documentary Festival

Ying says the Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia in 2010 and inspired pro-democracy protests in China in 2011, has played a part in the tightened state of repression.

“The year 2012 marks a shift into a period of total control,” Ying says.

“The increase in crackdowns since 2012 is the result of many outside influences such as the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 18th Party Congress [from which Xi emerged as the party leader],” BIFF’s Wang adds. “It is simply beyond our control.”

EMERGENCE OF INDIE FILM

Ying says documentary filmmaking in China emerged in 1989. That year, the Tiananmen Square massacre marked the end of the heady days of freedom and youthful optimism of the late-1980s. Rapid economic expansion soon replaced a desire for political freedoms.

“[It seems like] all Chinese signed a contract with the government: If you forget what happened, you can lead a normal life. If you don’t, then you have to leave or not have a normal life,” Ying says.

In the name of progress, the old world was quickly vanishing, along with its people, places and way of life. It was with a sense of urgency that many artists picked up a camera and started filming.

“Artists were driven by an urge to document everything, which was simply too overwhelming to be conveyed through painting and other art forms,” Ying says.

That was exactly what happened to documentary filmmaker Hu Jie (胡傑). Previously living and working as a painter in Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan (圓明園) Artist Village, Hu documented how Beijing authorities dismantled Yuanmingyuan and evicted or arrested its residents.

In Gansu province, Hu encountered a group of coal miners toiling in the mountains, whom he thought looked like “ghosts climbing up from hell.” At the time, it was taboo to tackle topics that would “make the working classes look bad.” Yet, Hu stayed in the miners’ hut with his camera.

“I thought if I capture their lives on video, then nobody would doubt the story,” the director says. “I had no idea what a documentary film was. I hadn’t seen any. There was no documentary cinema in China, only propaganda films.”

Soon, Hu discovered a not-too-distant past, one that had been deliberately erased from the Chinese people’s collective memory.

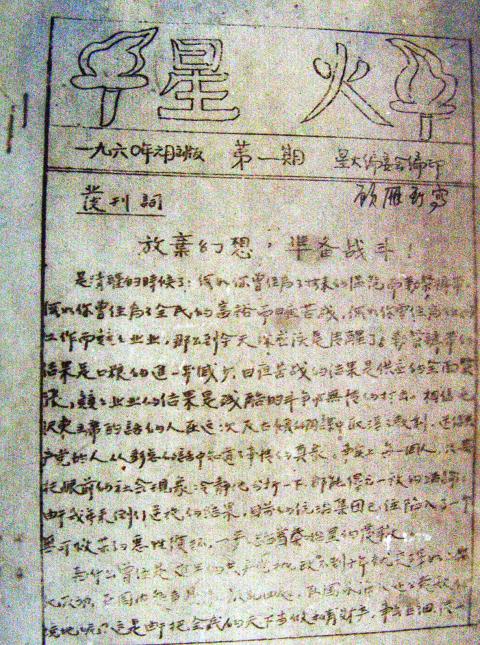

His 2013 Spark (星火), for example, explores the story behind Sparks of Fire (星火), the only surviving underground periodical from the time of the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign led by Mao Zedong (毛澤東) that led to the Great Famine. The film won the top prize at last year’s Taiwan International Documentary Festival (台灣國際紀錄片影展).

TAKING ACTION

In China, an “independent” film is independent not only from mainstream production but also the government’s censorship by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (國家廣播電影電視總局). As a result, independent works have no access to state media and are primarily shown at film festivals, like BIFF, universities, art spaces and other venues such as cafes and bookstores.

Ying says that in a heavily regulated society, an independent film festival is itself a form of activism, in that it provides a platform for discussion.

Documentary filmmakers are increasingly assuming the role of activist, creating works that address human rights violations, systemic corruption and other social ills. Both Ying and film scholar Zhang Xianmin (張獻民) say that independent filmmakers were first put in the spotlight in 2008 when big-name artist Ai Weiwei (艾未未) started making online videos and documentaries to expose social and political injustices.

“It was then that the government started to realize who these people making indie films really are and what they intend to do,” Ying says.

A CALLING

Independent documentary filmmakers in China are not professionals backed by investors, distributors and promoters. They are artists, journalists and teachers — even bank tellers and civil servants. They fund their own films with their own money.

“Sometimes, it is an effort made by the whole family,” Ying says.

Ying says an independent film festival not only provides a space to show and discuss films, but also creates a sense of community. Run by volunteers, these festivals are funded by private donations — mostly from festival organizers, filmmakers, friends and supporters. During the festivals, filmmakers come from all over China to speak with audiences and exchange ideas.

“Film festivals have very limited resources, but they send a clear message to filmmakers that it is worth doing. They are not hidden and unrecognized. Though not admitted to the mainstream media, their work has every right to be been seen and discussed,” Ying says.

SELF-CENSORSHIP

Compromising with authorities, however, is often necessary for the community to survive and grow. Hu says many independent filmmakers such as Ai Xiaoming (艾曉明) don’t show their work at festivals, knowing that the films, often highly critical of the government, can put festival organizers in a difficult spot.

“My home is in Nanjing. I know the people from CIFF very well, but I never participate in the festival. I am afraid that my works might cause them trouble,” Hu says. “It is a tacit understanding between the filmmakers and festivals. It is born out of necessity to protect and care for each other.”

Zhang, who co-founded CIFF in 2003, says “self-censorship remains a serious concern.”

Will CIFF return this year?

“It is a shell, a ruin, of its former self. This is the period of rehabilitation and reconstruction after the disaster. I can’t say any more,” Zhang says.

OUTSIDE CHINA

Ying is more outspoken now that he has been banished from the Chinese mainland. He says that the government crackdown has not only affected film festivals, but also independent filmmaking as a whole.

Ying says that an increasing number of film screenings and discussions are now taking place at less noticeable spots such as coffee shops and restaurants. Others are hosted outside of the country.

In Hong Kong, where freedom of speech still exists, Ying and a few friends have set up the Chinese Independent Documentary Lab (中國獨立紀錄片研究會), through which they will continue to make films, organize screenings, publish films and printed materials as well as hold workshops designed for people who don’t have access to filmmaking knowledge and facilities, such as factory workers.

“To me and those who are like me, it has become a necessity to carry on doing what has been banned back home,” Ying says.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the