Above Hell’s Valley in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投區), there’s a clearing where, when the steam dissipates, you can watch tourists circling the volcanic cavity, selfie-sticks waggling like cockroach antennae.

Beitou invites pathetic fallacy. The name derives from the Ketagalan for “witch,” the area evoking a bubbling cauldron. Prospecting for sulfur in 1696, Qing Dynasty official Yu Yonghe (郁永河) described “a big pot in which we are walking on the lid.” Two centuries later, George McKay noted the “hiss and roar.” But these growls hide whispers.

Opposite the hole in the foliage, for example, a distinctive building with a facade of blue wooden slats has long held its peace. Until recently, the story behind this location was suffocated by an obfuscation that even the dense sulfur clouds couldn’t match.

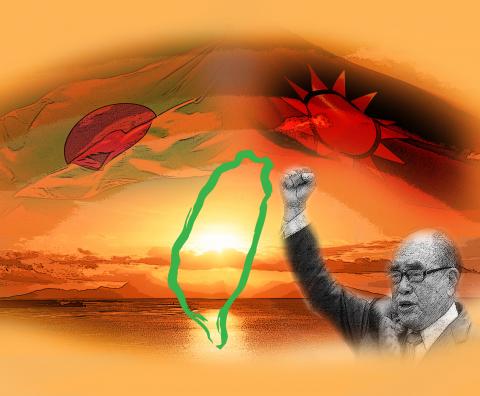

Photo: yang yuan-ting, Taipei Times

clandestine operation

For 30 years, 144 Wenquan Road (溫泉路) was the headquarters of the White Group (白團), a clandestine team of Japanese military advisers to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government. Now, thanks to the probing of a Japanese journalist, this startling episode of modern Taiwanese history has been laid bare.

For the KMT, the White Group ranks among the dirtiest of rags in an already overflowing basket of soiled laundry, and given the virulently anti-Japanese bent that some of the program’s graduates later assumed, their reticence to see the truth revealed is understandable.

illustration: kevin sheu

In January, Nojima Tsuyoshi, editor of the Chinese-language digital version of the Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun, published Last Empire Soldiers: Chiang Kai-shek and the White Group (最後的帝國軍人:蔣介石與白團), an account of the team’s time in Taiwan.

Covert Japanese assistance to the KMT in Taiwan began in 1949 when Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), whose forces had just fled China after losing the civil war, enlisted the services of Lieutenant General Nemoto Hiroshi to repel the communist advance on the outlying island of Kinmen.

Hiroshi’s tactics, which included allowing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces to land so they could be ambushed and nixing a KMT proposal to burn down villages where PLA soldiers had holed up, undoubtedly saved the KMT’s bacon. With the smoke barely cleared, KMT General Hu Lien (胡璉) swanned in to claim the victory. He was nowhere near Kinmen during the action.

While General Keh King-en (葛先才), the leader of an advance party to Taiwan, was publicly berating the nipponized Formosans for being a “degraded people,” Chiang was taking a much more pragmatic tack. In forming the White Group, he sought out top Japanese talent, offering benefits and hefty remuneration.

During the Japanese colonial era, a posting to Taiwan was considered an unenviable drag, but with postwar public sentiment in Japan now against senior military figures and employment hard to come by, Nojima says the White Group personnel looked on their Taiwan adventure as an opportunity.

the japanophile

The Generalissimo had a soft spot for the Japanese. Over the years, this had earned him the scorn and suspicion of party hardliners. Chiang spent six years in Japan, served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911 and spoke the language. Well aware that Japanese military know-how was a cut above what the KMT officer class had to offer, he was keen to make use of skilled ex-officers. Of course, he wasn’t about to advertise the fact.

As Nojima writes, it wasn’t just about a loss of face. Chiang could ill-afford to have the Americans offside and once the US made it clear that they were not happy with the arrangement, it was conducted in the shadows. Still, it was made just visible enough to provide leverage whenever American assistance wasn’t forthcoming.

Barak Kushner, who has written and spoken extensively on the White Group and the KMT’s complicated ties with Japan, sees the relationship as a marriage of convenience.

“Both [the KMT and Japan] essentially had become pariahs in their own region and their sole means of salvation was ironically in some measure to link up with each other,” Kushner says.

Although the alliance was informed by pragmatism on both sides, Kushner believes that there were other motivations at play.

“Perhaps the idea of pan-Asianism, which certainly was rife in higher KMT circles, many of whom studied in Japan prewar, still remained,” he says.

At the same time, Kushner says that the KMT had to look to all quarters for support. “Many would ask what other choice they had when US support looked desperate and Taiwan was considered a backwater.”

The White Group’s initial 17-man team was smuggled into Taiwan via Hong Kong in 1949. Participants were given Chinese noms de guerre, with the group named after its leader, Tomita Naosuke, who assumed the moniker Pai Hung-liang (白鴻亮). A former major general, Taiwan’s “Mr. White” was well known to Chiang having assisted KMT forces in the final throes of the civil war.

military legacy

Although the group’s remit was largely advisory, it is credited with introducing reserve officer exams and close combat techniques. Overall, at least 10,000 soldiers were trained under the group’s guidance.

At the behest of the US Military Assistance Advisory Group, the White Group was officially disbanded in 1959, though limited operations continued for years after. Tomita was persuaded to remain in Taiwan and was eventually made an honorary Republic of China general, the only foreigner to achieve this distinction.

Tomita continued to live at the house on Wenquan Road until his death in 1979 during a visit to Japan. At his request, his ashes were divided between his homeland and Taiwan. The latter portion of his remains can be found at Haiming Temple (海明寺) in Shulin District (樹林) in New Taipei City where they were placed by Chiang’s adoptive son Chiang Wei-kuo (蔣緯國).

The house at Wenquan Road is currently undergoing renovation. A spokesperson for the Beitou District Office confirmed that the property is now privately owned and unlikely to be open to the public any time soon.

However, early last year, a Japanese tour group, which included relatives of White Group officers, visited the location to mark the 35th anniversary of Tomita’s death. Tomita’s son expressed his pleasure that the historical record had finally been set straight.

raging against the japanese

Some people see things differently. In September last year, former Premier Hau Pei-tsun (郝柏村) addressed a seminar marking the 70th anniversary of Japan’s surrender. As reported in this newspaper, the aim of the event was to “debunk the lies fabricated by the Japanese bandits’ slaves who overstayed in Taiwan (滯臺倭奴) and who have distorted the real history.”

It was just the latest in a long line of anti-Japanese tirades by the 95-year-old Hau. A couple of months later, former vice president Lien Chan (連戰) was at it, branding Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) family “traitors” for adopting Japanese names when Japan ruled over Taiwan.

These race-card rants by KMT old timers are fairly standard. Yet, as has been pointed out, Lien’s comments are more than a little rich, given the pro-Japanese leanings of his grandfather, the historian Lien Heng (連橫).

One might also expect a little more circumspection from Hau. As one of the White Group’s most illustrious alumni, the four-star general was on intimate terms with the Japanese during a period when ordinary Taiwanese faced persecution for perceived Japanese proclivities.

Nojima has revealed that during his research he made three separate requests for an interview with Hau. On each occasion his correspondence went unanswered. This is hardly surprising. Coming clean now would expose the hypocrisy of a stance that has become an article of faith.

For all the harping about the importance of “true history,” the KMT has always been selective about what that history should include. For Hau and his ilk, the details of what went on behind the doors of 144 Wenquan Road is best left shrouded in Beitou’s mists.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

It starts out as a heartwarming clip. A young girl, clearly delighted to be in Tokyo, beams as she makes a peace sign to the camera. Seconds later, she is shoved to the ground from behind by a woman wearing a surgical mask. The assailant doesn’t skip a beat, striding out of shot of the clip filmed by the girl’s mother. This was no accidental clash of shoulders in a crowded place, but one of the most visible examples of a spate of butsukari otoko — “bumping man” — shoving incidents in Japan that experts attribute to a combination of gender

Last month, media outlets including the BBC World Service and Bloomberg reported that China’s greenhouse gas emissions are currently flat or falling, and that the economic giant appears to be on course to comfortably meet Beijing’s stated goal that total emissions will peak no later than 2030. China is by far and away the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, generating more carbon dioxide than the US and the EU combined. As the BBC pointed out in their Feb. 12 report, “what happens in China literally could change the world’s weather.” Any drop in total emissions is good news, of course. By