There’s no doubt at all that ThunkBook One is a worthy successor to the same stable’s Pressed, the English-language literary magazine for Taiwan that last appeared in 2009. The range of contributors is considerably wider now, with items from California, the UK, Australia and Stuttgart, and with several of the authors already boasting two or three books of stories or poems to their names.

It could be argued that writers come in five categories.

First are those with successful books published by major publishers, followed by those still largely unknown despite being published by major publishers. Third come those with books issued by small presses, fourth those without any book to date but with considerable promise and lastly beginners who have yet to make their mark. Pressed, on this analysis, largely survived on contributions from categories four and five. ThunkBook One, by contrast, looks like it’s flourishing on contributions mostly from categories three and four.

The standard is remarkably high. Reading the magazine through made me think that when I’m in a train, say, and looking at the other foreigners present, I usually imagine them entertaining rather routine thoughts. That some of them might be contemplating the kind of material printed here never occurs to me. I’m clearly laboring under a serious misapprehension.

Statistics first. There are 36 contributions in all: ten in prose, from ten authors; and 26 in verse, from 17 poets. Generally speaking, the prose seems to me superior to the verse. I judged eight of the ten prose items to be of some interest, but only six of the 17 poets to be at least reasonably competent.

My prize for best entry overall goes to H.V. Chao’s “The Scene.” This evocation of fashionable beach life on the coast west of Ahmedabad in the Indian state of Gujarat, has enormous reserves of irony and observation.Other items may have ambition without achievement, but Chao has both. He will please the general reader and the connoisseur equally. He boasts literary sophistication, in other words, while nowhere sacrificing total accessibility. This bright vignette deserves a prominent place in his forthcoming collection.

But other prose items stood out as well. Mark Paas, an old hand from Pressed days, contributes “Butterfly Scratches,” a chilling piece of dystopia set between 2026 and 2042 that would find a place in any literary publication.

Nicholas Sylvester’s story “DiJitz,” about a DJ who has a hard-drive embedded in one of his finger joints, is also memorable, though less strong than Paas’ contribution.

Also distinguished are “Untitled” by William Ceurvels, full of promise though short, Jonathan Butler’s “The Pigeon Master,” traditional in style but exceptionally perceptive, and Emily Hansen’s “TJ,” featuring a gay female hero and set in Iraq.

The poetry proved more problematic. Verse seems currently free to come in any fashion, but this very freedom can be seen as leaving its practitioners rudderless. They not only have to write a poem but create a style as well.

The contributors who navigate this rough sea best seem to be Quenntis Ashby, a multifaceted performer-writer currently based in Greater Taichung who contributes two unnerving items, and the UK’s P.A. Levy whose two poems are both concise and strong.

Other poets worthy of mention are Gale Acuff, Mary Whitmore, Carolyn Adams and Justine Gresson.

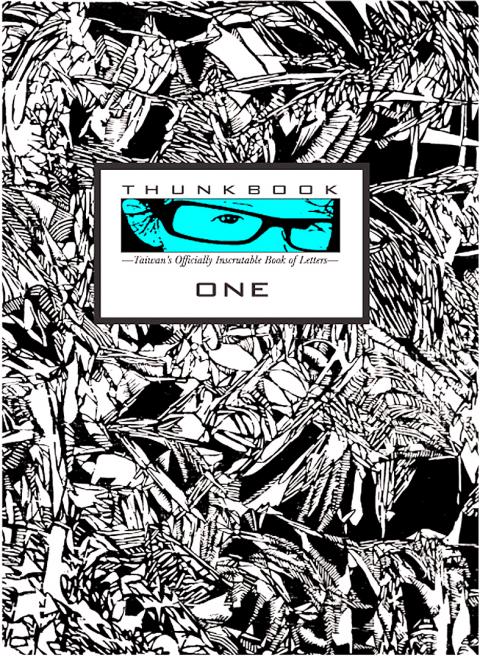

This leaves many worthy items unpraised. Joel McCaffery, for example, the magazine’s editor (he also edited Pressed) contributes a very professional piece titled “Curtain Call.” And the artwork, too, deserves celebration. Jon Renzella is responsible, and it comes in the shape of a gigantic woodcut — 123 cm by 186 cm in its original form — that is reproduced complete on the magazine’s last pages, and again in sections taken from it and distributed among the various items. It is entitled “Observations of the Corporate Person” and is surely a masterpiece of its genre. Renzella also provides the excellent cover design.

I have one moan. Some of the editorial matter is marred by a facetiousness that implies “We know we aren’t very good, but we’ve had a few beers and are going ahead anyway.” This tone belongs, if anywhere, to the early issues of Pressed and should now be quietly dropped. It’s inappropriate to the high standard of the new production.

Copies of ThunkBook One are available in Taiwan from Caves Books, among other outlets still to be finalized. Submissions for ThunkBook Two should reach thunkbook@gmail.com by Sept. 30. They should be under 3,000 words if prose, and under 100 lines if verse.

In brief, then, ThunkBook One is a very welcome addition to Taiwan’s English-language literary scene. Really this can scarcely be called a scene at all, but rather a sequence of sporadic appearances, a novel here and a reading there. ThunkBook as a result has the literary periodical field all to itself.

This is both an asset and a disadvantage — there’s no competition, but equally no companion to help set a fashion or prompt a discussion. Even so, this new venture appears all set now to go from strength to strength. Let’s hope the next issue will be even fatter than this one’s 136 pages.

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was