Bulareyaung Pagarlava, a Cloud Gate Dance Theatre performer and prominent figure in Taiwan’s performing arts scene, traveled to Hualien County in early 2012 to watch a performance by singer/songwriter Sangpuy Katatepan. After the show, Sangpuy asked Bulareyaung whether he could speak the Paiwan language, and the latter responded that he could only speak a little.

“If we cannot speak our mother tongue, how will we speak to the gods and our ancestors when we die?” Sangpuy, who is from Taitung’s Pinuyumayan community, asked Bulareyaung, who is a member of the Paiwan people.

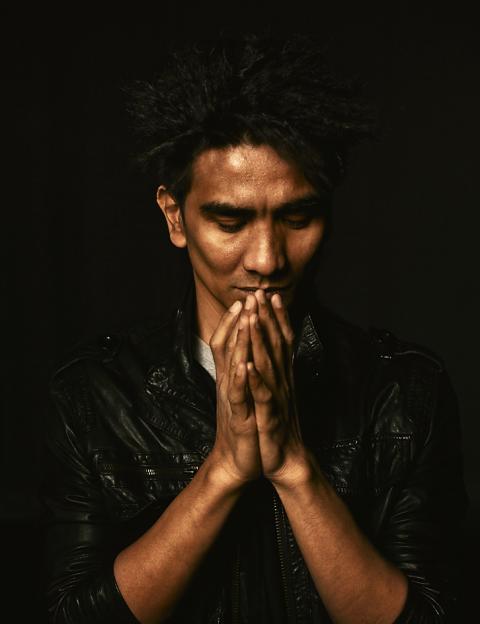

Though the two had just met in person for the first time, they already shared a history stretching back more than a decade. It was about 12 years ago that Bulareyaung first heard Sangpuy’s voice and was deeply moved by its power and passion. After watching Sangpuy’s performance, Bulareyaung promised him to do whatever he could to bring his music to a wider audience. For him, Sangpuy’s songs went beyond music, inspiring him to reconnect with roots he had lost long ago.

Photo courtesy of Bulareyaung Pagarlava

“He gave me the courage to know who I am,” Bulareyaung says.

As a youth, Sangpuy had been one of the few children in the tribal area of Katatipul, or Jhihben (知本) as it is known in Chinese, to learn the Pinuyumayan language, which was banned from being spoken in school when he was a child. So great was his skill and dedication that tribal elders asked that he extend the usual three years of training Pinuyumayan youth undergo when being groomed for potential tribal leadership to six.

Though Sangpuy wrestled with the decision, he and his family eventually agreed, even though this meant putting off finding a job, pursuing his musical career and even having a girlfriend. His training would be a full-time endeavor.

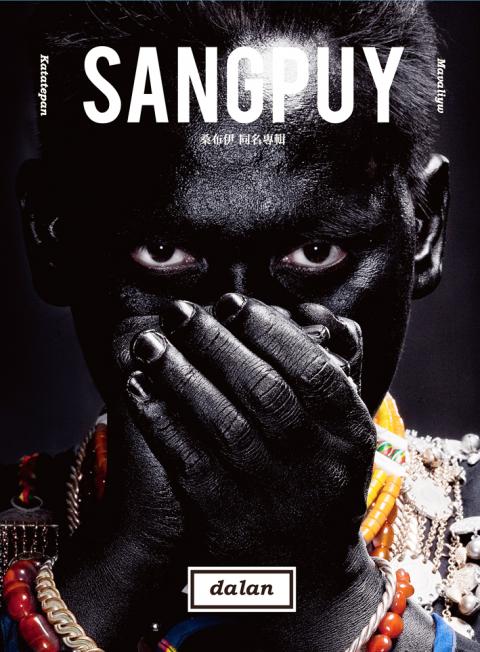

Photo courtesy of Wind Music

Bulareyaung, on the other hand, picked up just enough of the Paiwan language to get by as a youngster, all but abandoning his roots at the age of 14 when he left his village, also in Taitung County, for the southern port city of Kaohsiung. It was, he explains, something he simply had to do in order to further his education as well as his aspirations of becoming a dancer.

Today, the two men are united in the common cause of preserving Aboriginal culture. They agree that the ancient and now dwindling language of their forbearers is the key to keeping the traditions of their respective peoples alive. As Sangpuy puts it bluntly: “If you don’t know your language, it’s like you don’t exist.”

Sangpuy moved to Taipei eight years ago, working construction jobs by day while practicing his music by night. But his goal goes further than merely seeking fame and fortune. It’s about reviving a dying tongue.

“Most singers want to be superstars, but I don’t,” he says with a look of intensity. “I learned many songs from my elders, but as I grew up I saw that the young Beinan people did not speak our language, so they cannot sing the most beautiful songs. So I thought that if I have this album, the young generation can learn through it.”

The album Sangpuy speaks of is called Dalan. The CD came out last October, and Sangpuy has been touring Taiwan ever since. At one performance at Taipei’s The Wall (這牆) in March, a crowd of supporters — Aborigines, Taiwanese and those from overseas — listened as he explained the meanings behind his songs before launching into his original compositions and traditional Pinuyumayan chants set against an acoustic guitar. One such chant, Malikasaw, or “Cheerful Waggle Dance,” roused the crowd to perform the simple side-shuffle dance steps alongside several Pinuyumayan who had arrived from Taitung just for the performance.

Today, the Taipei-based Sangpuy and Bulareyaung frequently travel around Taiwan to Aboriginal villages and speak to youth about the importance of remembering where they come from. Bulareyaung has also started returning to his home village more often to brush up on his Paiwan, and to get to know his own culture again. His trips to other villages and his own are as much about imparting the importance of preserving Aboriginal culture as they are about inspiring young people to walk their own path — just as he did in pursuing a career in modern dance.

“I want to teach the young kids, but also share my own story; to tell them ‘Don’t be afraid to follow your dream.’”

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government