Not many Taiwanese novels become big sellers overseas, but a new book being promoted by a savvy literary agent in Taipei might break the mold.

Novelist and nature writer Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) is a soft-spoken, writerly Taipei native in his early 40s who first published The Man With Compound Eyes (複眼人) in 2011. The eco-fantasy has already been translated into English by Darryl Sterk, a Canadian expat living in Taiwan, and British and American publishers have been calling.

Gray Tan (譚光磊), Wu’s literary agent, has been busy promoting the book for more than two years and has already snagged three major publishers overseas.

Photo courtesy of GRAYHAWK AGENCY

A French-language translation by Gwen Gaffric is also in the works for a 2014 release in Paris.

Not only is the novel, Wu’s fourth book, set in Taiwan in the near future of 2029, it was translated by a Western expat who has long been a student of Aboriginal cultures and languages here.

Sterk said Wu’s 300-page novel can be compared to Life of Pi. “Both novels are inquiring into the meaning of life by throwing characters into the wilderness,” he said, adding that Wu’s novel is “strongly plotted with a sophisticated vision of nature.”

“The Man With Compound Eyes is a vision of nature, a kind of metaphor, a metaphor for our age, inspired as much by Marshall McLuhan as by insect eye biology,” Sterk added. “The main character’s eyes are like video screens, and there’s a video-mosaic effect.”

Sterk got the translation gig for Wu’s novel through a personal connection. He was introduced to Tan by a former teacher who knew both men.

“I spent the past five years immersed in Aboriginal representations in Taiwan, especially as produced by non-Aborigines, and there are many Aboriginal characters in Wu’s novel,” Sterk said. “Tan asked me first to do a translation of an excerpt from the book, so he could show it to an editor in London. One thing led to another and I ended up translating the entire book.”

Serendipity

Behind every international breakout novel, there’s an intriguing backstory, and Tan’s account as the agent promoting the book overseas is worth paying attention to. There’s serendipity and luck and good timing involved.

Tan said the novel was first picked up by Rebecca Carter, then an acquisitions editor at the Harvill Secker publishing company in London. From Britain, the book was sold to a major publisher in New York.

“I met Rebecca at the London Book Fair in 2011, and I was able to pitch Wu’s novel to her face to face there after talking about it in previous e-mails,” he said. “She seemed interested in this ecological fantasy by a Taiwanese novelist, and so I sent her an excerpt of Wu’s novel by our translator. A week later Rebecca said she loved the excerpt she read but wanted to know more, so I wrote a 20-page chapter-by-chapter synopsis for her. She immediately sent in an offer, and we closed the deal.”

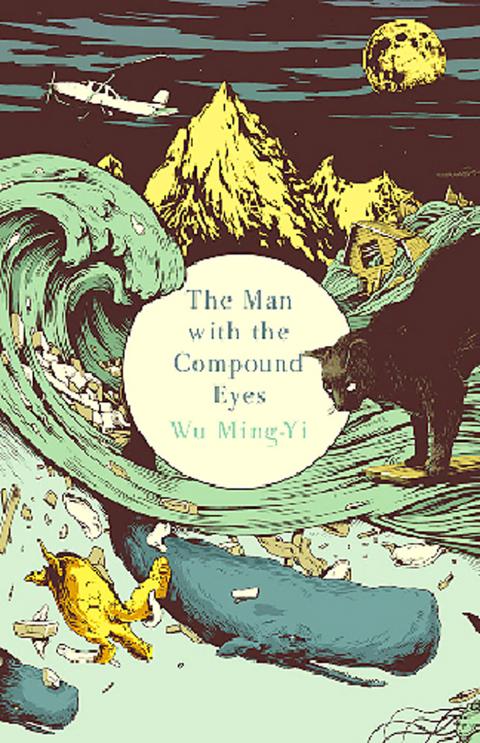

The arresting and colorful cover for the British edition has been done by the renowned artist Jim Wilson and can be seen online already.

Tan is positioning the book under the “international fiction” label, he says, adding that terms such as “speculative fiction” or “literary SF” are also fitting.

Ignored at home

Wu started writing The Man With Compound Eyes in 2006, he told the Taipei Times in an e-mail, noting that since publication in early 2011 sales have been steady, with the book now in its fourth printing — not a bad benchmark for authors in Taiwan.

But newspaper reviews of the novel have been sparse, according to Tan, with only one national newspaper reviewing the book. A few literature blogs have taken notice of the book, but plaudits for the book have spread mostly by word of mouth.

All this could change, of course, when Wu’s novel comes out in Britain and the US next fall, as Taiwan’s media will probably rush to print reviews by foreign newspapers.

When asked how he feels about the prospect of seeing his novel published in English and French overseas, Wu said that he’s “thrilled.”

“It means readers from different cultural backgrounds will be able to share in my story, and to discover and interpret what I’ve written in different ways,” Wu said. “They’ll also get a chance to better understand Taiwanese culture and literature.”

Government boost

While Taiwan’s mass media have not given much space to news of Wu’s book or its chances for success overseas, the government has been a big player behind the scenes, Tan said.

“The Ministry of Culture and the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立台灣文學館) have both been very much behind the book,” he said. “The museum gave translation subsidies to both the British and the French publishers, and the Ministry of Culture has been instrumental in helping us connect with some important international literary festivals.”

Gaffric, the French translator, is writing his doctoral thesis in France on ecological issues in Taiwanese literature.

“The novel oscillates between Taiwan settings and overseas settings, and it echoes global environmental crises that impact on everyone,” he said.

Critic Antonio Chen (陳建忠), writing about the book in Asymptote, an international online literary journal, has called it ‘’a masterpiece of environmental literature about an apocalyptic Aboriginal encounter with modernity.”

In the story that Wu weaves, “Taiwanese people are too interested in developing the east coast [in 2029] to clean it up,” he wrote.

Chen added: “Trash, resource shortages, and the destruction of Taiwan’s coastline as a result of the pursuit of unenlightened self-interest are unremarkable raw materials, but [Wu] mashes them into art. Seen through his compound eyes, daily life is dramatized and fictionalized, and the reader [is] inspired to feats of imagination and action.”

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of