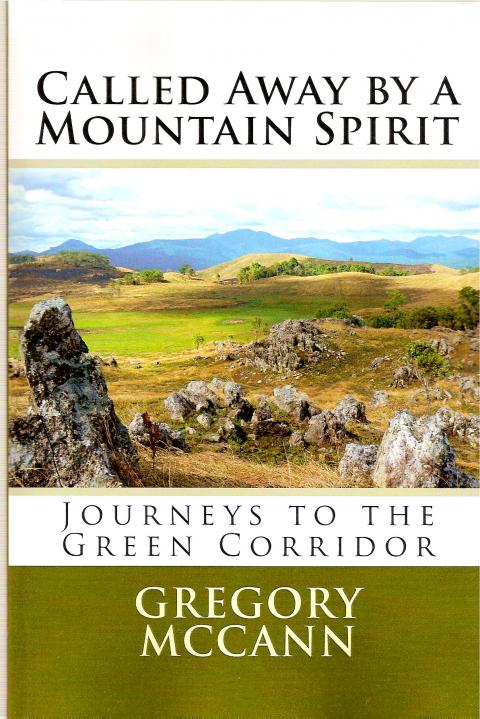

US enthusiast Gregory McCann is a lover of upland Southeast Asia, with its gibbons, tigers, rhinos, mountain spirits and tribal people. In Called Away by a Mountain Spirit: Journey to the Green Corridor he makes three trips to Cambodia’s remote northeast, to the Virachey National Park, parts of which, the guide on his first trip estimated, had only been visited by at most 200 tourists.

McCann lives in Taiwan, is married with one child and is studying for a PhD at Tamkang University in bio-regionalism, the doctrine that we should live on the natural products of our area rather than oranges from California and milk from New Zealand. His Cambodian journeys will feed into this thesis, he believes, as self-sufficiency is very much the style of the minority peoples he visits. But you get the feeling he’d be making the trips anyway, just for the pleasure of being there.

He has three particular enthusiasms. The first is the Southeast Asian light, which he thinks has a unique pastel quality. The second is the calling of gibbons in the early morning. And the third is traveling alone, a preference he shares with the classic English essayist William Hazlitt.

He loves nothing so much as plunging into a secluded lake after a day on the back of a motorbike, or of struggling up a muddy trail in dense forest to be presented with a view of unpeopled savannah. He strongly prefers animism to Christianity, and asks interestingly how it came about that animist beliefs are almost identical from China to Peru (they were transmitted through dreams, his guide replies).

But his mind darkens when it comes to ecological issues, and historical ones as well. Why is it, he wants to know, that not a single NGO concerned with conservation is currently in the area he so loves. With their motion-triggered camera traps and detailed observations, they could confirm the presence of several endangered species, and pressure the Cambodian government to put in place genuine safeguards rather than approving schemes for yet more rubber plantations.

This is an area close to the old Ho Chi Minh Trail, and McCann inevitably encounters the results of US actions during the Vietnam War. Then his rage boils over. How could any pilot be a party to unloading bombs and defoliants on a scattered rural population of hunter-gatherers whose way of life hadn’t changed in millennia, and who posed no conceivable threat to anyone?

There’s quite a bit about Taiwan in the book. As well as preparing his PhD, the author also teaches English at Chang Gung University. Having failed in a letter-writing campaign on behalf of the Virachey Park and its Veal Thom grasslands, he began incorporating Taiwan ecological issues such as the dying coral near Green Island and the fate of the Formosan Black Bear into his English-teaching materials. The sea dumping of sewage was responsible for the damage to the coral, he points out, while the local bear had less spent on it by the government than two pandas in Taipei Zoo.

But McCann has remarkably wide sympathies, and this makes the book doubly attractive. He enjoys a trip to a conference in Japan, for example, saying how much he loves the place and how he appreciates the novelty and eccentricity of its culture. There’s no mention of Japanese whaling.

But in essence McCann is a proponent of conservation in all its aspects. He’s an enemy of the toxicity of civilization, and praises food produced without the aid of hormones or antibiotics. Agribusiness, mining, logging, poaching and the cash economy in general are his foes. He sees the concept of “natural resources” — everything he admires viewed as profit — as free money for self-interested politicians. Development is tragedy for him.

His second trip to Cambodia is in the company of a fellow American language-teacher. The arrangement turns out to go against McCann’s belief in trekking alone, however, and the two predictably have an argument about Buddhism versus animism, though they unite to cure a child with an infected sinus, sponsoring him for a trip to a distant hospital.

McCann makes his third trip in response to an email appeal from his guide — 400 men armed with chainsaws were preparing to put an end to the supposed “national park” as they’d known it. After contacting all the newspapers and NGOs he knows, he decides to try to make one last attempt to reach the spirit mountain of Haling-Halang on the Lao-Cambodian border. He fails, finding logging and poaching rampant and everyone with any authority on the take. He ends the trip by drowning his disappointment and dancing with local teenagers to amplified Lao pop-music.

This book is depressing in its general drift. Not only is there little hope for Virachey, most of which has now been scheduled for mining exploration, but a Sumatran forest area McCann takes an interest in is, as the book closes, about to be bisected by two new roads, opening the way for poachers and illegal loggers. The course of action the author opts for in these cases is not less tourist access, however, but more. Only in this way might effective pressure be brought on the authorities.

It may well be, as McCann surmises, that his love for these places is rooted in childhood experiences back in the US. But when the causes someone espouses are as admirable as this, the deep motives that drive them become irrelevant.

All in all, Called Away by a Mountain Spirit is a well-written account that mixes description with passionate advocacy. It’s self-published through CreateSpace, but it seems to me that, given a little light editing, it could well be re-issued by a commercial publisher — if, that is, McCann can find one with sufficiently clean environmental credentials. For the time being, the book can be bought through Amazon.com.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,