The shrill voice of a North Korean woman serves as the discordant background to the barely audible murmur of Magnum photographer Chang Chien-chi (張乾琦), an auditory juxtaposition that shows how Chang blends into the background of Asia’s most repressive police states. Even when speaking he’s an inconspicuous presence.

No, we are not in Pyongyang, but at TheCube Project Space (立方計畫空間) in Taipei’s Gongguan (公館) neighborhood, where we are discussing Escape From North Korea (脫北者) and Burmese Days (在緬甸的日子), two exhibitions of his that depict, from different perspectives, life in those totalitarian states. The screeching voice, a kind of noise pollution, is a sound installation that gives the listener a sense of what people in North Korea must regularly endure.

TheCube show presents five large-scale black-and-white photographs — four taken on a trip to Pyongyang last year — and Escape From North Korea, a video installation that documents the dangerous journey a group of North Korean defectors underwent to escape. The video earned Chang the 2011 Anthropographia Award for Human Rights.

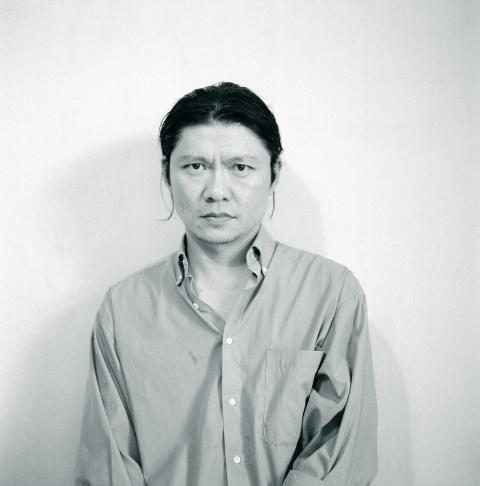

Photo courtesy of Chang Chien-Chi/Magnum photos

The second exhibition, Burmese Days, is on view at Chi-Wen Gallery (其玟畫廊). It presents about a dozen color photographs taken during Chang’s travels throughout Myanmar, as well as a video installation meant to give viewers a taste of the many contradictions within Burmese society. Both exhibits are based on photographic essays shot for National Geographic. Though the exhibits are at different venues, they are thematically linked. The works on display document the poverty afflicting the majority of people living in these repressive countries and the tenacity of the human spirit in the face of oppression.

What is striking about both series is the physical absence of what George Orwell called Big Brother. Sure, there are the monumental edifices built by and for these dictators — the military junta’s lavish new capital in Naypyidaw, or Pyongyang’s shrines built for the “Great Leader” Kim Il-sung and “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-il. But for the most part, Chang’s subject matter is the average person struggling to make it through another day.

Burmese Days, for example, features several psychologically penetrating images of democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi. But the faces of the generals who rule over Myanmar with an iron fist are nowhere to be found. The same series includes photos of people living with HIV and AIDS, farmers, fishermen and monks, all rendered with Chang’s exceptional sense of geometric composition, but nothing of the wealthy ruling class. There are photos of the Kachin Independence Army, but nothing depicting Myanmar’s official military apparatus.

Photo courtesy of Chang Chien-Chi/Magnum photos

Escape From North Korea shows a 2008 picture of a defector, the young woman’s despondent face looking away from the camera; linked to this shot is a black-and-white photo of a socialist realist painting of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-song rendered as though they are deities.

Burmese Days and Escape From North Korea contrast Chang’s earlier work — the portraits of shackled mental patients in The Chain, for example, or his sardonic look at Taiwan’s wedding industry in I Do, I Do, I Do and Double Happiness — in that he is no longer examining an institution within society, but society itself.

Taipei Times: What is the backstory of Burmese Days, the gallery exhibit based on Burma: Inside the Land of Shadows?

Photo courtesy of Alberto Buzzola

Chang Chien-chi: After completing Escape From North Korea, National Geographic asked me where I would like to go next, and I said Burma. Initially my proposal was to follow the route George Orwell took when he was a policeman in upper and lower Burma — but from the perspective of present-day Burma as a police state. But somehow the idea of following the route of George Orwell was not well received but the idea of Burma as a story was positively approved, thus the journey through the Land of Shadows began.

TT: Had you already visited Burma before you started putting the proposal together?

CCC: I’d been there twice before, but only for short visits. Before the assignment, I did as much research as I could, but also tried to go there without preconceived ideas because I wanted to avoid taking pictures that had been done already.

TT: What, in your opinion, are those “pictures that have been done already,” and how are your images different?

CCC: When I am in areas where tourists are permitted, I try to push the visual boundary. When I am in restricted territories, I refuse to compromise visually. When I was working in Guatemala, a Catholic priest told me: “It’s better to ask for pardon than permission.”

TT: Did you read Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four or Burmese Days as a means of preparing yourself for the project?

CCC: I started reading Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1980 and didn’t finish it until four years later. I didn’t get through Burmese Days.

TT: Did you encounter any run-ins with Big Brother, or the state apparatus?

CCC: Oh yeah, but I operate or function on the basis that I’m being watched. And there are times that they blatantly let you know that you are being watched. This is especially true with the new capital [Naypyidaw]: they want you to know that you are being followed. [The authorities] have succeeded in manufacturing this feeling that you are being watched; it’s ubiquitous. It’s most obvious in front of Aung San Suu Kyi’s residence and the National League of Democracy office.

TT: Did you manage to photograph any of these secret police, or “little brothers working for Big Brother,” as you have called them?

CCC: I managed to take some pictures, but they are more informative than evocative. In the end, those pictures were not used for publication or in the exhibition.

TT: Is being watched by the state police something that you’ve grown used to in your professional work?

CCC: No, it’s something that I could never get used to.

TT: You grew up in Taiwan during the Martial Law era. Did these early experiences help you gain greater insight into Burma?

CCC: There were times when I was in Burma and it was kind of deja vu … Did it help? I don’t know. It did reinforce [the fact] that they are watching.

TT: What is the underlying reason for choosing the projects on North Korean defectors and Burma?

CCC: You mean besides the fact that they were assignments? I see there is something that I feel connected to — so much so that I can continue after the assignment is finished. Both projects [Burma: Inside the Land of Shadows and Escape From North Korea] share one thing in common, which is uncertainty in a repressive state. We don’t know if we are going to have access. We don’t know what is going to happen next. But one thing is certain: you have to assume that you are being monitored and listened to, and then work from there.

TT: Is access just an issue with Burma and North Korea, or is this a more general problem that you’ve experienced?

CCC: It’s in a more general sense. It’s the omnipresence of images. People are more cautious because they don’t know where this is going to appear. Overall it’s getting tougher with sensitive or touchy subjects and/or subject matters.

TT: How do you compensate for that?

CCC: Patience, patience, patience. Move with caution. If I don’t accomplish it this time then I will return. But that is a luxury because most publications will not give this kind of support. If it’s my own project, then I would for sure continue out of my own pocket.

TT: One thing that seems to differentiate Burma: Inside the Land of Shadows and Escape From North Korea from earlier projects, is that the links between their subject matter is less obvious.

CCC: If you look at The Chain, for example, as both a simile and a metaphor, there is a relationship: there is bondage, there is tradition or there is obligation. You see the people who come together [by choice], like in I Do, I Do, I Do, [while in] others it is not so clear, as in Double Happiness. And then you see people in China Town that, yes, they were together but they are also far apart. But even in Escape From North Korea, it’s still there. Once settled in South Korea, the defectors still want to get their family members out. That’s sort of their goal. Trying to reconnect this broken link. But it’s not so much so in Burma — at least for now.

TT: In a broader sense, what links all these different projects?

CCC: It’s difficult to put into words. It’s all very personal. They were sort of self-developed over time to the point where [each] is a link that not only exists, but is re-defined over time.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall