Marjie Popkin thought she had chemo brain, that fuzzy-headed forgetful state that she figured was a result of her treatment for ovarian cancer. She was not thinking clearly — having trouble with numbers, forgetting things she had just heard.

One doctor after another dismissed her complaints. Until recently, since she was functioning well and having no trouble taking care of herself, that might have been the end of her quest for an explanation.

Last year, though, Popkin, still troubled by what was happening to her mind, went to Michael Rafii, a neurologist at the University of California, San Diego, who not only gave her a thorough neurological examination but administered new tests, like an MRI that assesses the volume of key brain areas and a spinal tap.

photo: EPA

Then he told her there was something wrong. And it was not chemo brain. It most likely was Alzheimer’s disease. Although she seemed to be in the very early stages, all the indicators pointed in that direction.

Until recently, the image of Alzheimer’s was the clearly demented person with the sometimes vacant stare, unable to follow a conversation or remember a promise to meet a friend for lunch.

Popkin is nothing like that. To a casual observer, Popkin seems perfectly fine. Articulate and groomed, she is in the vanguard of a new generation of Alzheimer’s patients, given a diagnosis after tests found signs of the disease years before actual dementia sets in.

But the new diagnostic tests are leading to a moral dilemma. Since there is no treatment for Alzheimer’s, is it a good thing to tell people, years earlier, that they have this progressive degenerative brain disease or have a good chance of getting it?

“I am grappling with that issue,” Rafii said. “I give them the diagnosis — we are getting pretty good at diagnosis now. But it’s challenging because what do we do then?”

It is a quandary that is emblematic of major changes in the practice of medicine, affecting not just Alzheimer’s patients. Modern medicine has produced new diagnostic tools, from scanners to genetic tests, that can find diseases or predict disease risk decades before people would notice any symptoms.

At the same time, many of those diseases have no effective treatments. Does it help to know you are likely to get a disease if there is nothing you can do?

“This is the price we pay” for the new knowledge, said Jonathan Moreno, a professor of medical ethics and the history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I think we are going to go through a really tough time,” he added. “We have so much information now, and we have to try to learn as a culture what information we do not want

to have.”

Some doctors, like John Morris of Washington University in St Louis, say they will not offer the new diagnostic tests for Alzheimer’s — like MRIs and spinal taps — to patients because it is not yet clear how to interpret them. He uses them in research studies but does not tell subjects the results.

“We don’t know for certain what these results mean,” Morris said. “If you have amyloid in your brain, we don’t know for certain that you will become demented, and we don’t have anything we can do about it.”

But many people want to know anyway and say they can handle the uncertainty.

That issue is facing investigators in a large federal study of early signs of Alzheimer’s. The researchers, who include Morris, have been testing and following hundreds of people aged 55 to 90, some with normal memories, some with memory problems and some with dementia. So far, only investigators know the results. Now, the question is, should those who want to learn what their tests show be told?

“We are just confronting this,” said Richard Hodes, director of the National Institute on Aging. “Bioethicists are talking with scientists and the public about what is the right thing to do.”

RISK LEVELS,

BUT NO SCORES

Rafii learned about the new tests and how to use them because he is an investigator in that large federal study. But many who come to the memory disorders clinic at UC San Diego, where Rafii works, are not part of that study, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, and simply want to know what is wrong with their brains.

So Rafii sometimes offers the study’s diagnostic tests: spinal taps and MRIs to look for shrinkage in important areas of the brain; PET scans to look for the telltale signs of Alzheimer’s in the brain. He calls it “ADNI in the real world,” referring to the study’s acronym. Others, too, offer such tests, although doctors differ in how far they will go.

Mony de Leon of New York University, for example, takes a middle ground. He is studying people at increased risk for Alzheimer’s or other dementias, especially those whose mothers had Alzheimer’s. That sort of family history, he has found, makes the disease more likely.

Many who come to his clinic have no memory problems but are worried. So De Leon enrolls them in a study and regularly subjects them to an array of tests — ones that probe their memory, and ones like spinal taps and brain scans that look for signs of Alzheimer’s. But he only provides people with a sort of general assessment, telling them they are at increased risk, decreased risk or somewhere in the middle.

“We do not reveal their scores,” De Leon said.

INFORMATION’S BURDEN

At Boston University, Robert Green faced an ethical dilemma. He wanted to test people for a gene, APOE, that has three variants. People with two copies of one of the variants, APO e4, have a 12 to 15-fold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. People with even one copy of the gene variant have about a threefold increased risk.

Five published consensus statements by ethicists and neurologists had considered the question of whether people should be told the results of APOE tests. And every one of those committee said the answer is no, do not tell.

Green wondered if that answer was right.

“It seemed rather strange to be in a position where family members are coming to you and saying, ‘I really understand APOE genotyping and the idea of a risk gene, and I want to know my genotype,’ and then to say to them, ‘I could tell you that, but I’m not going to.”’ After all, he said, “Part of what we do in medicine is to inform.”

He knew what it meant to tell people they were at high risk.

“Alzheimer’s is a fearsome disease,” he said. “You can’t get much more fearsome than Alzheimer’s.” And yet, he said, “People still wanted to know.”

He decided to do a study to see what would happen if he told.

The first surprise was how many people wanted to know. To be in the study, a person had to have a first-degree relative who had had Alzheimer’s, making it more likely that they would have an APO e4 variant. Green thought maybe a small percentage of the people he approached would want to have the genetic test. Instead, nearly a quarter did.

“Frankly, we were terrified in early days of this study,” Green said. “We did not want to harm anyone. We were very, very thoughtful and intense. We sat with people beforehand and asked if they were really sure they wanted to do this.”

But his subjects were fine with the testing. After they gave the subjects their test results, researchers looked for psychological effects, observing participants in conversations and administering standardized questions designed to detect anxiety or depression or suicidal thoughts. They found nothing.

The main difference between those who found out they had APO e4 and those who found out they did not have that gene variant is that the APO e4 subjects were more likely to buy long term care insurance, were more likely to start exercising and were more likely to start taking vitamins and nutritional supplements, even though these practices and products have never been shown to protect against Alzheimer’s.

For many, though, the news was good — they did not have APO e4.

THE DAYS GET HARDER

In San Diego, Marjie Popkin said her memory problems had gotten steadily worse in the year since she first saw Rafii.

For example, she says, she has two cats. “I have to remember when I walk out that door that they can’t come with me.”

She used to read “all the time.” Now, she says, reading is difficult. She depends on a friend, Taffy Jones, who took her to her appointment with Rafii, and who visits often and calls her every day.

But that is hard for Jones.

In many respects, Jones said, Popkin is perfectly normal. She remembers to feed her cats, she changes their litter box every day, she showers.

“Other things she is not able to deal with at all,” Jones said. Getting dressed has become a problem, and Jones has to call Popkin every morning and every night to remind her to take her pills. Popkin can no longer drive and relies on Jones to help with routine things, like getting groceries. Helping Popkin has become a time-consuming chore.

Popkin is all too aware of the situation she is in, dependent on the kindness of neighbors and Jones.

“I am trying to adjust, but it’s not easy,” Popkin said in a telephone conversation. “I am pretty pragmatic. I know what the score is.”

Sometimes she sits in her apartment and just cries and cries. She has no family, and Jones is her only remaining friend; the others have drifted away.

The diagnosis of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease was a shock, Popkin said, like “a punch in the stomach.”

Her only consolation, she says, is that her father, her last remaining family member other than a cousin in North Carolina, died a few years ago, before she got the diagnosis. “He would have been devastated.”

And Popkin — is she glad now that she found out what is wrong?

“I wish I didn’t know,” she said.

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

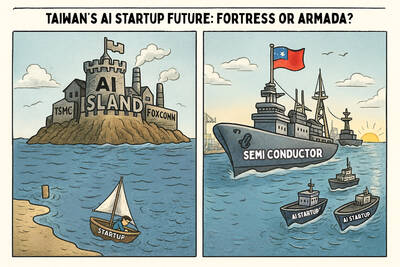

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government