At 10am on May 25, I was nestled into the deep plush of a velvet sofa three floors above Bond Street in central London with a mustached architect dressed head to toe in eyewateringly tight black leather. He talked in a breathy, conspiratorial whisper about philosophical happiness and had me bend down to join him in lovingly stroking the carpet, which, he told me, was woven in a little workshop he owns in the Caribbean. In a changing room nearby, everyone from old-school aristocrats (Lady Helen Taylor) to latest-edition paparazzi-darlings (Daisy Lowe) was wriggling in and out of dresses, choosing which “looks” to borrow for a glitzy dinner in the evening. On the ground floor, uberstylist Katie Grand was holding court in pink sunglasses while a cleaner flicked non-existent dust from a case containing Princess Margaret’s luggage. A moving sculpture by the artist Michael Landy entitled Credit Card Destroying Machine (component parts: antlers, teddy bears, rusty tools; and yes, it works) whirred away by the glass doors outside which Alexa Chung, in the midst of getting ready to host a live feed of party arrivals on Facebook, was having a cigarette break.

Welcome to the new Bond Street palace of Louis Vuitton, which takes the dark art of luxury retail to a new level. For starters — despite the racks of handbags, luggage and clothes — this flagship, which opened to the public on Friday, is not — repeat not — a shop. I was told many, many times before I even set foot in this three-years-in-the-making temple to the Louis Vuitton brand that it is a maison, not a store: “Reflecting Louis Vuitton’s art-de-vivre and savoir-faire, conceived as the home of a collector ... [it] gives visitors opportunities to discover new and exciting experiences.”

Which is daft, of course. But then the Louis Vuitton belief that retail is about emotion looks less and less silly with every set of figures the company releases. LVMH, the fashion house’s parent company, reported 11 percent sales growth in the first three months of this year, rewards reaped from audacious global expansion — last month, two new Louis Vuitton stores opened in Shanghai in one day — and from a strategy of focusing on the brand’s heritage in a more glamorous age of travel, which has hit a chord with customers. Research in Japan, where 60 percent of households own a genuine Louis Vuitton product, suggests consumers are prepared to pay 50 times as much for the real thing as for a fake, even if the products appear identical, because of the feeling of “specialness” they get when they purchase the real thing.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

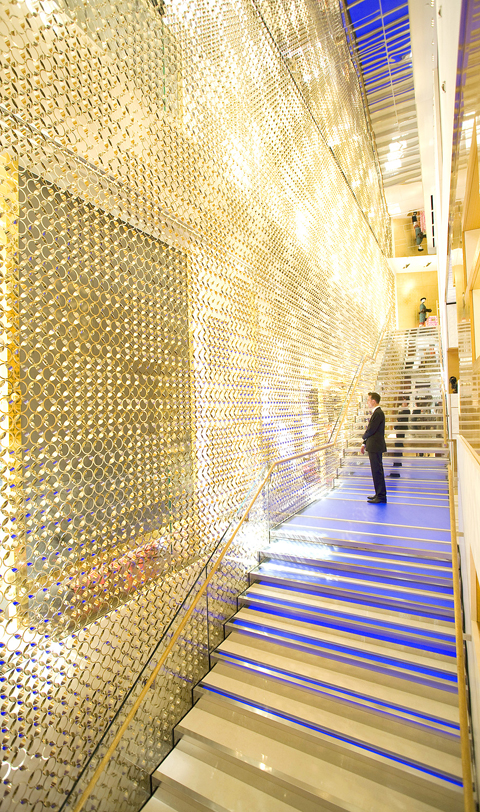

The glass front of the Bond Street store is lined from floor to ceiling with a monogrammed golden chainmail that filters a sunny light on to the shopfloor. Facing you as you enter is a custom-made travel caviar set, in crocodile. (There is, of course, nothing as vulgar as a price tag.) Beyond, there is a wall of vintage trunks and another of current season luggage. The “bag bar,” where you can sit on a leather barstool and watch a moving display of handbags behind the counter, was inspired by the shooting-duck gallery of the funfair. (With Kiki, a giant sculpture by Japanese artist Takashi Murakami next to it, it also looks a little like a conveyor-belt sushi bar.)

At every turn, the boundaries between art and fashion are deliberately blurred. A huge self-portrait by Gilbert and George hangs between the two walls of men’s tailoring; in the exhibition space, Katie Grand, a longtime collaborator of the Louis Vuitton designer Marc Jacobs, has curated an exhibition of catwalk fashion. In the “library,” Barry Miles’ book, London Calling: A Countercultural History of London Since 1945, sits alongside limited-edition artists’ notebooks with covers by Gary Hume and Anish Kapoor. The top-floor “apartment,” where specially invited guests can make their selections in private, boasts a Basquiat, a Koons, another Gilbert and George, and two Richard Prince pieces.

Amid the walls of glossy bamboo and others wallpapered in silk and then hand-papered on-site with silver lacquer, and the hand-carved marble monograms sunk in the floor, architect Peter Marino cuts an improbable figure. He is dressed in his trademark biker leathers (custom-made at Dior), and completes the look with a cap and moustache. Marino, a flamboyant figure in the fashion world since his first job renovating a New York townhouse for his friend Andy Warhol, has become the go-to guy for jaw-dropping luxury flagship stores, including the Chanel Tower in Ginza, Tokyo, and the Christian Dior flagship in Paris.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Just don’t call them luxury. “I am totally throwing up over the L word right now,” says Marino, who alone among the smooth, money-oiled LVMH machine is gloriously off-message. “The PR department will keep pushing that word, but since when did retail have to be so self-important and serious?” When Marino was first approached for this project, he refused — because he had designed the previous Louis Vuitton store on the same site, legend has it he said it would be “like eating my babies” — but he changed his mind. Are you happy now, I ask him? “Do you mean philosophically, or emotionally? I think maybe I’m too old now to be happy emotionally. But I try to be happy philosophically.” Actually, I say, I meant the store, do you like it? Marino throws his head back and laughs; his assistants and PR, hovering behind him, shoot nervous glances, clearly dying to rein him in. “The store! Of course. That’s hilarious. The thing is, I just want somewhere I feel good, a nice place to be, somewhere my wife would buy a handbag and then not be dying to get the hell out straight away. You know what I mean?”

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,