Pho is a French word? Who knew?

One of the most popular dishes from Vietnam to make it to restaurant tables around the world, from New York to London, is pho. There’s pho bo and pho ga and pho tai and more.

And while the jury’s still out, it is widely believed by linguists and word sleuths that the word pho is not a Vietnamese word, but in fact comes from the French term pot au feu (pronounced ‘‘poh oh fuh’’). The word was likely introduced to Vietnam by French colonialists more than 100 years ago, according to longtime Vietnam resident Didier Corlou, a top French chef in Hanoi. Corlou told a food seminar in Hanoi in 2003 that pho most likely was a transliteration of the French term for hot pot.

The list of French “loans words” still used in Vietnam today is gaining recognition as young Vietnamese become more curious about their nation’s past, 23-year-old Abby Nguyen of Ho Chi Minh City told the Taipei Times in a recent e-mail exchange.

Before the Americans got involved in a long and protracted war in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, the French had been heavily involved in the country for more than 300 years, she said. From 1853 to 1954, Vietnam was a French colony. As a result, Vietnam’s colonial past has left an indelible mark on the country’s language.

The Vietnamese word for cheese, for example, pho mat, comes from the French word fromage — say it out loud slowly — and cake is called ga to, from the French word gateau.

The word for butter — bo — comes from the French word buerre.

During a recent research expedition via keyboard and the Internet, this reporter came across more than two-dozen “loan words” from French still used in Vietnam today, in addition to pho mat and ga to and bo.

To understand all this, it helps to know a little French, but even if you never studied French in high school or college and you don’t know bonjour from bonsoir, “amusez-vous bien.” That means: “Enjoy!”

Liver pate is called pa in Vietnam today. Pate chaud, according to Californian foodie Andrea Nguyen of the Viet World Kitchen blog, is called pa so.

There’s more, according to sources in Vietnam and overseas. Ba — father in Vietnamese — comes from the French word papa, many linguists believe.

Va li comes from the French word for suitcase — valise.

Bia comes from the French word for beer, biere.

A doll is called a bup-be in Vietnam, from the French word poupee.

What to call the necktie on that senior civil servant giving a press conference on Hanoi television? It’s a ca vat — from the French word cravate.

Doc to comes from the French word docteur, which is not far from the English word doctor.

Phac to comes from facteur, the French word for mailman.

Phim means “movie” and comes from the French word film.

A pha is a headlight on a car or motorscooter, from the French word phare.

Motorscooters and motorcycles are themselves are called moto — from the French term motocyclette.

If you make a mistake in France, it is called a faute. In Vietnam today, people often say phot for mistake.

Bit-tet is from the French term biftek — beefsteak, or just plain steak.

Coffee is called ca phe, from the French word cafe.

Wine is called vang (vin).

Soap is called xa bong (savon).

A circus is called xiec (from the French word cirque).

Ben Zimmer, a noted US-based word maven who writes the weekly “On Language” column for the New York Times, pointed this reporter to the work of Milton Barber, whose 1963 paper, The Phonological Adaptation of French Loan Words in Vietnamese, was eye-opening, to say the least.

MaryJo Pham, a senior at Tufts University in Boston who was born in Vietnam and came to the US as a young girl, said she has been informally collecting French loan words used in Vietnam over the years.

“Piscine is still in use for ‘swimming pool,’” she said in an e-mail.

“And cyclo, or ‘xich lo’ in Vietnamese, is what we call a bicycle-drawn rickshaw.”

“Yogurt — yaourt in French — is called da ua in Vietnamese. Ice cream is called ca rem from the French word creme.”

A clothes zipper is called a phec mo tua in Vietnamese, from the French word fermeture, Pham said. A woman’s bra is called su chien from the French word soutien, she added.

“You can see how some French loan words influenced the actual transliteration of words — for motorscooters, women’s bras, coffee, frozen yogurt, baguette sandwiches — things that were and are indispensable to daily life in Vietnam,” Pham said. “‘Bo for butter, from the French buerre, is still definitely in use in Vietnam. And phim for movies, film, cinema, yes.”

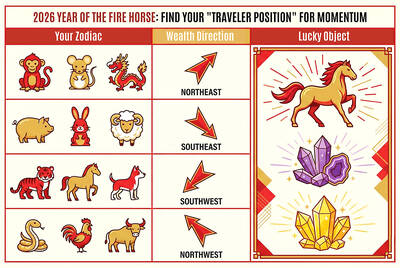

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moving the Doomsday Clock to 85 seconds before midnight last month symbolized the closest humanity has ever been to global catastrophe In this context, the legislature remains gridlocked over the general budget, mirroring tensions simmering across the globe. According to local soothsayers, this “extreme speed and violent conflict” is no coincidence as the Year of the Horse is the year of bingwu (丙午), the rare “Fire Horse Year” (火馬年) that occurs once every 60 years, a configuration carrying an energy that shapes everything from personal fortunes to international crises. “For some people, it can be a

Feb. 16 to Feb. 22 Pai Ko’s (白克) film career appeared poised to reach new heights in 1962 with the completion of the highly-anticipated, star-studded Romance of Longshan Temple (龍山寺之戀). Despite being mainly in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), the film promoted harmony between those born in China and Taiwan, aligning with the official cultural policy at the time. However, he soon disappeared. Colleagues found out he was arrested and accused of colluding with communists. It was not his first run-in with the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). As a university student in China, he joined the anti-Japanese Anti-Imperialism League and