Last month, Johnny Weir, the US figure skater, switched one of his costumes for the Vancouver Olympics after he said he received threats from anti-fur activists for accessorizing his already colorful wardrobe with just a touch of white fox. At almost the same moment, fashion designers in New York were showing fall collections with so much fur that they seemed to collectively stick a thumb in the eye of political correctness.

Did the designers forget that wearing fur is fraught with controversy? Or did they simply stop caring?

There were fancy fox cuffs (Oscar de la Renta), wild-looking coyote capes (Michael Kors), bizarrely colorful mink jackets (Chris Benz, Peter Som), knitted furs (Proenza Schouler, Diane Von Furstenberg) and capes trimmed with raccoon tails (for men, courtesy of Thom Browne). The following week, the runways of Milan were perhaps even hairier, from the fur-collared coats at Prada to the fox mukluks at D&G.

For the first time in more than two decades, more designers are using fur than not. Almost two thirds of those in New York are, based on a review of more than 130 collections that were shown on Style.com last month, which is a surprising development during a recession. And it didn’t just happen because of some idea that was floating around in the collective designer ether.

Rather, fur became a trend because of a marketing campaign.

Over the last 10 years, furriers have aggressively courted designers, especially young ones, to embrace fur by giving them free samples and approaching them through trade groups — sometimes when they are still in college. Last summer, for example, the designers Alexander Wang and Haider Ackermann, plus Alexa Adams and Flora Gill of Ohne Titel were flown to Copenhagen for weeklong visits to the design studios of Saga Furs, a marketing company that represents 3,000 fur breeders in Finland and Norway. Saga Furs regularly sponsors such design junkets. The designers were given carte blanche to use fur with state-of-the-art techniques.

Wang and the Ohne Titel designers ended up including fur in their fall collections. Ackermann, in Paris, included fur scarves and a narrow wool jacket with ribbons of fur protruding from its collar.

“We were seeing all of these new possibilities in which you can use fur in a very light way,” Adams said. “Fur gives a richness in texture. It’s like discovering something new that also has an interesting history.”

Several young designers echoed that sentiment, saying they were less interested in fur as a luxury statement or an act of defiance than as a novel design. Wang said he had not intended to use fur in his collection but decided to after seeing so many plush fabrics that resembled fur. “The point was to create that rich, luscious feel while blending the lines between what was real and what was fake,” he said.

In Denmark, Adams said, she learned of a technique of sewing extremely thin, evenly spaced strips of fox onto a layer of silk, creating the look of a fox coat with a third of the weight and expense. For their show, she and Gill showed a version in army green. Carine Roitfeld, the editor of French Vogue, admired it, so the designers sent the sample, which would cost US$10,400 in a store, to her hotel for her to wear throughout Fashion Week. Roitfeld was photographed so often in the coat that they decided she could keep it. After all, their cost to make it was nothing.

Much like lobbying groups in Washington, various cooperatives representing breeders, farmers and auction houses around the world solicit designers to use their furs. Saga, one of the biggest cooperatives, provided the furs used this season by the New York labels Cushnie et Ochs, Thakoon, Brian Reyes, Wayne, Derek Lam, Proenza Schouler and Richard Chai, in addition to Ohne Titel and Alexander Wang.

Another cooperative, the North American Fur Auctions in Seattle, gave furs to the newcomers Bibhu Mohapatra and Prabal Gurung and worked with marquee designers who make separate fur collections, including Carolina Herrera, Oscar de la Renta and Michael Kors.

“We’ll give them furs to make three, four, five, even six different garments,” said Steve Gold, a marketing director for the North American group, which represents farmers in Canada and the US. “The quid pro quo is simply that they mention our name to the press.”

Neither marketing group would disclose its budget, but Gold said it was typical to spend “hundreds of thousands of [US] dollars” each year.

“We want to make sure fur is on the pages of magazines around the world,” he said. “The way to do that is to facilitate the use of fur by designers.”

Their success has infuriated anti-fur activists like Dan Mathews, the senior vice president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, who described the fur marketing as “a smoke and mirrors campaign, where they give designers money and free fur to accessorize the runway, even though that stuff never ends up in shops.”

Several of those designers are too young to remember the vicious battles over fur in the 1980s and 1990s, when a PETA member tossed a dead raccoon onto the plate of Anna Wintour while she was dining at the Four Seasons; another tossed a tofu cream pie in De la Renta’s face. But some remain sheepish on the subject. Thakoon Panichgul, for example, showed a coat in his fall collection with strips of fox bursting from the sleeves, but he declined to be interviewed for this article because of the controversy.

Others said they felt confident using fur after examining the chain of production and finding it humane.

“You see so much leather and shearling being used this season, and no one is complaining about that,” Adams said. “I don’t see the difference between using shearling and using fur.”

Saga sponsors courses and competitions at design schools, including at the Fashion Institute of Technology and Parsons the New School for Design (as does PETA).

“We bring them knowledge about fur early in the design process,” said Charles Ross, the director of international activities for Saga.

That is how Irina Shabayeva, the winner of the sixth season of Project Runway, was introduced to fur. In 2003, while a student at Parsons, Shabayeva won a fur design contest sponsored by Saga. The prize was a trip to Scandinavia. After Shabayeva started her own collection, Saga introduced her to Funtastic Furs, a company that makes furs for designers like Peter Som and Catherine Malandrino.

“They were kind enough to sew up a few pieces for me,” Shabayeva said. Actually, her fall collection looked as if it had been conceived in a taxidermist’s studio. The opening look was a dress made of the long plumes of a pheasant.

The sales of fur in the US, and its appearance on the runways, fell in the 1980s as a result of the aggressive protests. But attitudes began to change, and fur began to make a slow comeback, from sales under US$1 billion in the US in the early 1990s to US$1.8 billion in 2006, according to figures released by the Fur Information Council of America. Naomi Campbell, who once posed for PETA, now has a fur coat named after her at Dennis Basso.

But many of those gains were erased in the last three years, following an unusually warm winter in 2007, and then the recession. There was little fur on the runways last year, as designers sought to rein in prices.

Now, as fur is becoming trendy, skin prices at auction have shot up in response to increased demand; the price of a male mink pelt approaches US$100 in Finland, up 40 percent over last year. A silver fox pelt is now US$200, up 20 percent.

That raises questions about how good this trend will be for the designers, should stores buy their furs. Most have little experience in the fur market, and they will have to pay for the specialized production of their designs, which is far more expensive than ready-to-wear made from fabric. And if their fur pieces don’t sell next fall, they will be stuck with a lot of expensive coats.

“That’s a big question mark,” said Brian Reyes, whose show included several pieces made for him by Funtastic Furs. “The fur industry has different ways of buying or selling. Who buys it? Where does fur sell well? It’s all a new experience.”

In his showroom sits a big cobalt blue fox coat — so big, Reyes said, it could stand up on its own. The price was US$6,750. Though he showed several fur coats, he does not expect to sell many this year, as he is just beginning to test the market and wants to be cautious.

But other designers are already taking orders. Ohne Titel sold more than 15 shearling and fox vests, priced under US$2,000, in the days after its show. Derek Lam, who has worked with Saga for several years, has found fur designs to be lucrative. From his pre-fall collection in 2008, Lam sold 148 short riding jackets trimmed with mink, which cost US$1,990. Now Lam offers furs priced from US$4,500 to US$30,000.

“If you sell two,” said Jan-Hendrik Schlottmann, the chief executive of Derek Lam, “you are doing really well.”

Of the fox coat worn by Roitfeld, even without the sample, Ohne Titel already has orders from stores for 10.

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

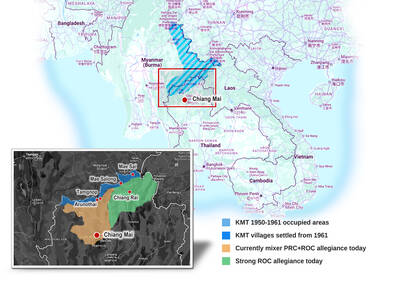

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers