As blue-eyed blondes increasingly hog the catwalks, discrimination is also at work in the weird and wonderful world of the fashion mannequin.

“Black mannequins don’t sell,” said Marc Lacroix, a manager at one of the world’s leading producers, Paris-based Cofrad which also owns Los Angeles firm Patina-V, a maker of ethnically diverse fashion mannequins.

“Black and Asian models have been doing fine for a long time in the US, and we have customers in Britain. But in France, Germany and Austria, forget it!” he said.

“The Anglo-Saxon world, it seems, is more open-minded than the old continent.”

Mannequins come in all shapes, colors and sizes but always come apart — just like jointed artists’ models made of a head, body, legs and arms.

“We only sell headless, limbless bodies to Saudi [Arabian] customers,” he said. “Couture clients too often like them headless as they want potential buyers to focus first on the clothes.”

“Asian customers,” Lacroix added, “which often represent big global labels, prefer European-looking mannequins as they have a more universal appeal.”

Mannequins, nowadays generally made in environmentally unfriendly fiberglass, are relatively new in historical terms — as are the top models they more than often mirror.

Initially a tool for a tailor or seamstress, dummies made of cane surfaced in the 18th century before being made of wire and later cardboard. But it was only in the 20th century that couture came up with the idea of using mannequins rather than live models to display clothes to wealthy women at private showings.

Their widespread use in shops and shop-windows followed in the 1950s and 1960s, when couture and ready-to-wear labels multiplied, and big-name top models such as Twiggy emerged.

“Mannequins are very important,” said Helene Lafourcade, who heads visual merchandising for French department store giant Galeries Lafayette. It uses 15,000 mannequins across its network, including 5,000 alone in its big central Paris stores near the Garnier Opera house.

“They’re not just objects you stand up in the store. They’re static salespeople,” said Lafourcade, who reckons mannequins multiply sales fourfold.

Mannequins are crafted by sculptors in a process every bit inspired by a catwalk show.

A manufacturer calls a modeling agency, organizes a casting session and commissions the male or female model chosen to pose for a photographer. The sculptor uses the pictures to make a cast.

With an average life-span of three to four years, mannequins can cost anywhere from US$220 to US$2,200 for the cream of the crop.

In the 1990s, said Franck Banchet, artistic manager for Paris department store Printemps, the trend was for hyper-realistic dummies.

“The Rolls Royces of the mannequins then were by Adel Rootstein in London, who used professional make-up artists and hairdressers to work on them.”

When minimalism became the design statement of the day, mannequins too became streamlined, “their faces just an oval shape with a line for a nose and a line for a mouth,” he said. “Top of the pops was a mannequin by Swiss firm Schlappi.”

Couture king Yves Saint-Laurent’s taste for such stylized faceless mannequins, often lacquered in white or black or gold, turned the tables on the trade.

“Most people nowadays use the cheaper stylized faceless mannequins,” said Banchet.

In Paris to launch his new collection of mannequins called Madame, New York’s Ralph Pucci said, “you have to create mannequins that are relevant to the times.”

“Mannequins are about change, about art, about sculpture,” said Pucci, who has worked with avant-garde artists such as Andree Putman, Ruben Toledo, Kenny Scharf and Stephen Sprouse.

“As for body shapes, every time we try different sizes, it fails. It’s not relevant. A mannequin has to have personality and has to sell the clothes.”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

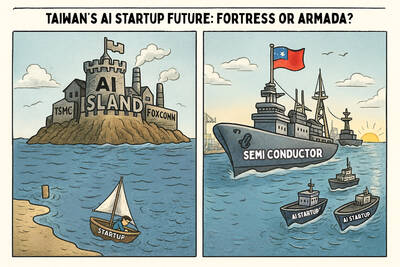

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it