On March 24, 1989, a massive tanker captained by a man who had allegedly been drinking, sailed outside regular Alaskan shipping lanes and hit a reef, causing one of the worst environmental disasters in US history.

The Exxon Valdez, at the time one of the most advanced tankers in the world, split, spilling approximately 40 million liters of crude oil into the delicate and pristine Arctic environment of the remote Prince William Sound.

The oil dispersed over an area of 28,000 km² and covered approximately 2,000km of rugged coastline. It killed an estimated 600,000 to 700,000 birds, fish and sea mammals.

Twenty years later, another horrific accident is waiting to happen, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) warned on Friday, even as the damage from Exxon Valdez continues to blight the region.

In a graphic illustration of the lingering effects of that disaster, the environmental group sent oil-crusted rocks to ministers, officials and media in the Arctic countries still wrangling over arrangements to govern a renewed resource rush to the region.

The rocks accompanied a report titled Lessons Not Learned, which recommends a moratorium on new offshore oil development in the Arctic “until technologies improve to a point where an adequate oil-spill clean-up operation can be performed.”

WWF also recommended that the most vulnerable and important areas of the Arctic be deemed permanently off-limits to oil development because oil spills would be next to impossible to clean up or would cause irreparable long-term damage.

“Governments and industry in the region remain unprepared to deal with another such disaster,” WWF warned. At the same time global warming is melting more of the ice, which increases access and exploration, making another accident more likely.

“While there has been little improvement in technologies to respond to oil-spill disasters in the last 20 years, the Arctic itself has changed considerably and is much more vulnerable today,” said Neil Hamilton, leader of WWF’s Arctic Program.

“Sea ice is disappearing and open water seasons are lasting longer, creating a frenzy to stake claims on the Arctic’s rich resources — especially oil and gas development. We need a ‘time-out’ until protective measures exist for this fragile, special place.”

Bill Chameides, dean of Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment and a member of the National Academy of Sciences, agrees with the WWF that despite one of the largest cleanup efforts in history much of the damage has proved irreversible.

Though many beaches and coves in the area look the same, the deeper picture tells a very different story. Digging even a little uncovers a gooey mix of oil and sand.

“People may assume that because the spill happened 20 years ago, the effects are long gone. But they persist — and may continue for years to come,” said Chameides, who estimates that it could take as much as 100 more years for all the oil to dissipate.

Oil giant Exxon spent about US$2 billion on the cleanup operation.

It was originally ordered to pay US$5 billion in punitive damages. But in a successful series of court appeals culminating in a Supreme Court decision last year, that amount has now been reduced to just over US$507 million — a tremendous blow to the fishermen and local communities who suffered from the calamity.

“Their way of life was devastated,” says local resident Sharon Bushell, the author of a book called, The Spill, Personal Stories From the Exxon Valdez Disaster. She interviewed residents about how they remember the disaster and chronicles the lost lives of the fishermen, innkeepers and mechanics.

“There was death everywhere, dead birds, dead otters, dead deer. A vast amount of oil covered the water,” said one woman. “It was a terrible scene, one to rival anyone’s idea of hell.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

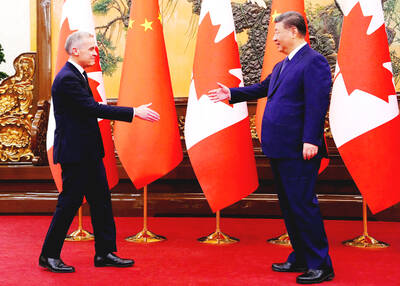

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director