In China, by the early 1970s, the worst excesses of the Cultural Revolution were over, the Tiananmen protests and the military crackdown well in the future.

And for Jan Wong (黃明珍), a 19-year-old Canadian college student of Chinese descent, who had come on a summer’s visa, had stayed on to study at Beijing University, and had joined student work teams at a machine tool factory and on a dust-blown farm, China was “radical-chic,” and “Maoism was mesmerizing.”

In her 1996 memoir, Red China Blues, Wong described her experiences from those years as like “living inside a real-life propaganda movie.”

Buried in the memoir was an incident that had occurred at Beijing University. Another student, Yin Luoyi, had confided to Wong and a Chinese-American classmate that she wanted to go to America, and asked their help. “We decided,” Wong wrote, “[that] Yin did need help” and “the Communist Party would save her from herself.” So they “snitched,” turning her in to the Foreign Students Office. “We actually thought we were doing the right thing,” Wong wrote.

But the incident, so matter-of-factly recounted in Red China Blues — and, more importantly, what its outcome had been for Yin — haunted Wong for 30 years. In A Comrade Lost and Found she returns to that story.

Returning from China in the early 1980s, Wong worked as a journalist, including a stint as a business reporter at the Boston Globe. Later, as the Toronto Globe and Mail’s China correspondent, she covered the Tiananmen protests.

Then, in 2006, with her husband, a Canadian whom she had met and married in Beijing, and their two teenage sons, Wong returned again to China. It was time, she writes, “to find Yin, apologize and try to make amends.”

It is a quest, like that in Red China Blues, both intensely personal and at the same time one that delves into the conflicted history and culture of China.

The chances of finding Yin in a city and society so changed were not good. For the city, the structure of the ancient capital, especially the narrow, crooked residential hutongs, was fast disappearing.

As for the personal quest, Wong falls back on networking — itself not that easy in a city where a person is likely to change phone numbers seven times in a decade.

She finds an old roommate, and then other classmates, even her long-ago adversaries like the hard-line disciplinarian whom she knew as “Fu the Enforcer.” Perhaps, Wong thinks, “the landscape of her memory is littered with bodies,” and, after all, “snitching in Chairman Mao’s China was routine and easily forgotten.”

Then, with time running out before Wong and her family must return home, the connections came through, and Yin called.

There is a happy reunion, and over several days Yin describes her road from exile in the Manchurian oilfields back to a privileged life in Beijing, reinventing herself several times along the way as an officer in the People’s Liberation Army, a law school professor, then as a businesswoman, even briefly working in New York. Her life, Wong reflects, “had been one high-stakes gamble.”

Yin invites Wong to her high-rise condo — one of five residences that she and her husband own. Tiantongyuan (天通苑) had been the site of a labor camp for class enemies. But its name, then and now, means “straight to heaven,” prompting Wong to reflect that Yin herself “has gone straight to heaven.”

As for Wong, she wonders “what the revolution was all about.” She had judged Yin when she had talked of going to the US, and now was judging her because of her success. “Even at this late date,” she writes, “I still need remedial help to recover from Maoism. Come to think of it, writing this book is tantamount to a Maoist self-criticism.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

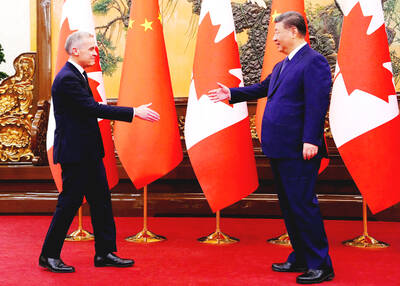

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director