As a rule, I avoid conversation on flights. Partly because diazepam makes me slur and partly because I was told never to talk to strangers. But, as it transpires, I am something of a novelty on this flight. I’m heading for Banjul, capital of Gambia, and all around me sturdy geriatric twitchers are sipping gin and tonics and popping antimalarials.

I am the flight’s youngest passenger and small talk will be unavoidable. Queuing for the toilet an elderly man cracks a joke about blood pressure and offers me a pear drop. I steer the conversation to birds. “I’ve been coming here for 20 years,” he tells me. “The coast is the place for bird-watching.” I tell him that we, too, are staying by the sea. “Well, be warned: the lads aren’t used to young girls. I’d pop that ring onto the other finger.” He winks. Twenty years ago, removing the ring or indeed anything of vague worth would have been better advice.

Tourism is still in its early stages. But in recent years, thanks to low prices and a dramatic improvement in its hotels, Gambia is an increasingly popular winter sun destination, it is also — my fellow passengers notwithstanding — starting to lure a younger crowd.

The newest and most flashy hotel, the Coco Ocean Resort & Spa, opened just after Christmas. Here, twitchers and honeymooners alike check in in their droves beneath a sky that teems with life. On the hotel lawn, white cattle egrets will sidle up to your lounger while, above, vultures circle like predatory biplanes. There are so many birds that when asked which kind is eyeing up your breakfast, staff simply grunt “owl.”

Laid out with no evident symmetry just off Bijilo beach, the Coco has 58 rooms and suites — all cleaned and bug-sprayed twice daily, and all on a colossal scale. A few of the rooms are in the main building; most are individual villas scattered throughout grounds so extensive they would take 25 minutes to traverse on foot. I count three loungers per head and five waiters per diner. On each section of lawn — they’re all surrounded by baobab trees — lurk further surplus members of staff, all resplendent in their palm-green-colored uniforms.

A tropical garden planned for the rear of the hotel will add another half hectare and another 14 gardeners. Towards the beach, the grounds are bordered on one side by a shabby cafe manned by an over-friendly body board vendor and on the other by the Bijilo Forest nature reserve, which, despite the hotel’s high bougainvillea walls, sporadically expels Colobus monkeys from its canopy onto the hotel terrace. Dining here is a lazy, seven-star experience, with chipper waiters and hearty portions. Three dinners in, my body begins to protest at the extraordinary amount of seafood I am throwing at it and I debate leaving my claypot tuna under the table for the invaders, since feeding them bananas is prohibited by management.

The Coco Ocean’s unique selling point is its spa, which is Gambia’s first. Housed in a Moorish-style villa, with domed ceilings, stark white walls and marble floors, this place oozes opulence and can be as taxing as you want it to be. Guests can work up a sweat on a treadmill or fizz the dead skin off their backs in the thalassotherapy pool. I ease myself into the grandeur with four treatments: a foot massage, followed by a facial and an Indonesian back massage with herbal compresses, and culminating on day five with a Moroccan hammam rub.

In the treatment rooms they switch off the piped music because the sea is so wonderfully booming, and by day two my feet, which have been cocooned in thermal socks for five months, feel reborn. On day three I fall fast asleep during the facial and awake shiny-cheeked ready for an equally faultless back massage that leaves me smelling of dead flowers. Day four brings my hammam treatment: steaming, washing, mud pasting and scrubbing. It isn’t unpleasant. It merely offers a glimpse into my inevitable, incontinent future.

By day five I am incapable of brushing my own teeth and ill-prepared for what lies beyond the hotel’s walls. Out here, the real Gambia is wild and stark. The sun is strong and the wind stronger. Markets swell with people, and roads are red dust and tarmac. Goats sniff at eggshells and the cattle look haggard but, according to our driver, make good steaks.

Even the coastline, rolling and white and palm-tree’d though it is, can be off limits to bathers. Every morning, just beyond the grassy knoll, the danger flag would be hoisted, red and ugly. There are two pools at the hotel, but in a fit of rebelliousness, I venture knee-deep into the sea on day one and am ushered out by a steward.

Unlike in many Caribbean resorts the beaches of Gambia aren’t private, so expect to see local men working out like it’s Venice Beach. There is security, though, and how necessary this is becomes apparent when one guest has her bag snatched by a local “bumster” (the Bradt Guide has a whole chapter on these guys). I ask a steward whether this happens regularly. He shakes his head and says things are much improved since the 1980s. He tells me the bumsters are chancers, and I decide to regard the bag-snatching as just a stroke of bad luck. He advises me not to go on to the beach alone but when I do, carrying my digital camera, I am ignored.

For some people Gambia still comes with unpleasant connotations — malaria and sex tourism, not to mention the Fultons, the British couple recently sentenced to a year’s hard labor for bad-mouthing the president. But these shouldn’t be overstated. There was an outbreak of malaria among British tourists in December, but I am well-provided with malarone and Deet, and am not bitten once. The sex trade may still exist (Shirley Valentines were once common), but we see no clear evidence of it. And as for what happened to the Fultons, we simply avoid discussing the president with anyone.

Poverty remains widespread, of course, and some may find it hard to cope with the contrast between the smart resorts and what lies outside their walls. But for those looking for the African Caribbean, and affordable winter sun luxury, the Coco Ocean seems likely to prove a hit.

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

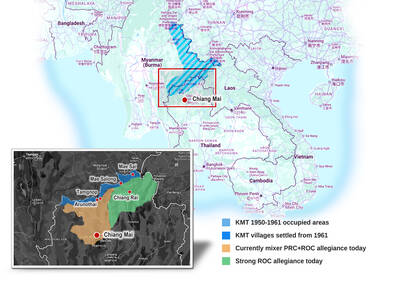

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers