Seventeen years have passed since Terry Tempest Williams gave us Refuge, an indelible meditation on her mother’s battle with cancer and the devastation wrought on a bird sanctuary by rising waters in the Great Salt Lake.

Since then, fans of this Utah native and naturalist have come to expect a common thread through her books: the artful weaving of observations from the natural world with the labyrinths of the human experience.

For Williams, this is not a stock formula. It’s her sublime art.

Now she delivers Finding Beauty in a Broken World, an ambitious, even audacious, work.

Williams takes us from the breathtaking, Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna, Italy — a city she has spent time in — and uses them as a metaphor for two communities, a besieged prairie dog colony in Utah and a village in Rwanda, where she helped build a memorial to victims of a 1994 genocide that killed 1 million in that African country.

That’s quite a juxtaposition, all delivered against the not-so-tacit backdrop of the Iraq war and the Bush administration’s foreign-policy adventures.

Although Williams made her reputation as a naturalist and defender of the West’s wild places, in recent years she has turned her eye toward the broader world.

Still, in her view, genocide in Rwanda can be equated to the war waged against the prairie dog, and vice versa. It is all about humanity’s inability to recognize, at least in a sustained and universal way, the worth of communities.

The Utah prairie dog is one of six species in the world viewed as most likely to become extinct in the 21st century. Of course, this assessment was made in 1999, before global warming and its impact on polar bears was fully appreciated.

Prairie dogs have long endured “varmint” status in the West. Ranchers despise them because cattle and horses have a way of stumbling into their holes, breaking legs. Beyond that, they were viewed as vermin that spread vermin.

Now they are threatened just as much by the tract homes sprouting in the New West. So these creatures, pack animals who communicate in distinct dialects, are torched and gassed in their holes.

“We are all complicit,” Williams writes. “A rising population is settling in subdivisions. The land scraped bare. The prairie dog towns and villages are being displaced. Sad, sorry state of habitation. They are prisoners on their own reservations.”

The Rwandan village Williams visits is Rugerero. Today it is home to massacre survivors from three villages that were erased from the Earth. The violence was tribal, Hutu killing Tutsi. Much of the butchering was done with machetes. As one aid volunteer informs Williams: “That’s Rwanda.”

So much savagery amid such beauty. Here is Williams limning the Rwandan landscape: “We arrive in Gisenyi at dusk. Smoke. Shadows. Figures captured in headlights. Lake Kivu is a long reflective mirror. I am reminded of scenes captured in a ring I once had as a child; inside a plastic orb were the silhouettes of palms against a twilight sky made of iridescent butterfly wings, turquoise blue. We are surrounded by enormous mountains, a crown of peaks, snow-tipped and jagged. And then, suddenly, an eerie red glow is emanating from the Congo. An active volcano.”

We live among such a disconnect in this world: apart from nature, apart from each other. It’s a comfort to have Williams in our midst, reminding us of the mosaic formed by every creature on Earth.

But that comfort is also our challenge.

“Shards of glass can cut and wound or magnify a vision,” Williams tells us. “Mosaic celebrates brokenness and the beauty of being brought together.”

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

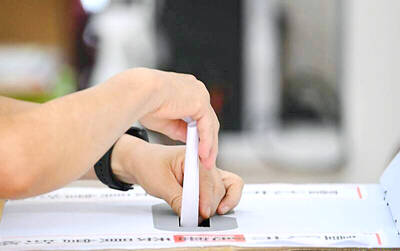

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s