John Darnton was 11 months old when his father, Byron Darnton, was killed off the coast of New Guinea while covering World War II for the New York Times. His father’s sacrifice propelled Darnton toward his own four-decade career at the Times, a job that was filled with its fair share of adventure and excitement: In 1977, while serving as the paper’s West African correspondent, he was jailed and then expelled from Nigeria, a turn of events that was least partly the result of his friendship with the marijuana-loving Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti.

Two years later, when the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was driven from power, Darnton was on the scene, poking around in the deposed strongman’s basement refrigerator to see if he really did keep human hearts on ice. (He didn’t.) He was in Poland for the birth of the Solidarity movement and the establishment of martial law, and he won a Pulitzer Prize for a series of dispatches he smuggled out to avoid censorship.

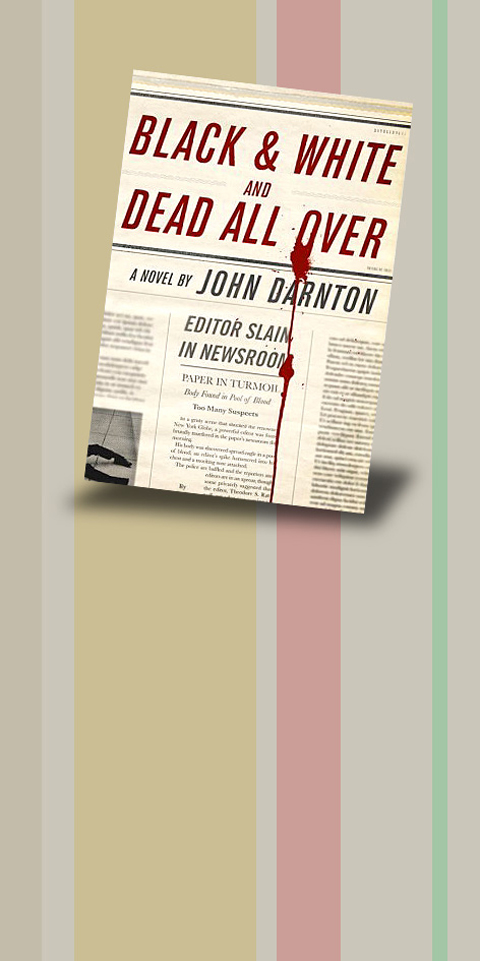

With this type of personal narrative, it’s no surprise that a publisher signed Darnton to write a memoir about his father’s influence on his own life. Darnton, however, had a more difficult time writing about himself than he did about others, he has said, so he turned to this, his fifth novel, as a “kind of avoidance book.” The result, a murder mystery that unfolds in the newsroom of a thinly disguised family-run broadsheet headquartered near Times Square, is a satirical roman a clef that draws in equal parts from Elmore Leonard and Evelyn Waugh.

When the book opens, the New York Globe is fighting for its survival, with the bean counters on the business side pushing for staff cuts and a crass New Zealand media mogul named Lester Moloch plotting a takeover. Those existential threats to the paper’s identity seem less pressing after Theodore S. Ratnoff, a tyrannical assistant managing editor, is discovered in a pool of blood on the newsroom floor. Ratnoff was reviled for his withering put-downs of the paper’s copy editors — “critical notes of Teutonic exactitude” — and attached to the editor’s spike sticking out of his chest is a piece of paper with the same two-word phrase Ratnoff used when he would fire off the rare attaboy inquiring as to the author of a particularly advantageous headline: “Nice. Who?”

The story of Ratnoff’s murder is assigned to Jude Hurley, a 35-year-old metro reporter who lives in an East Village walk-up with his German shepherd-Irish setter mix. Hurley, like his progenitor, is an old-school romantic, a shoe-leather reporter who gets off on “the adrenaline rush of working on deadline and nailing a story just right” and who clings to the quaint belief that a journalist’s job is “to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.” When the novel opens, his most pressing problem is figuring out what to do about Elaine, his tedious “almost-live-in girlfriend.”

He’s soon overwhelmed by more immediate concerns, which include catching a killer, staying alive and navigating a nascent flirtation with Priscilla Bollingsworth, the overeducated homicide detective assigned to the case (and one of the novel’s several cliched characters). Ratnoff, it turns out, was just the first of the killer’s victims, and as the bodies pile up in the newsroom, everyone from the beaten-down hack in the next cubicle to the scheming executive in the boardroom emerges as a potential suspect.

Throughout, Darnton does a wonderful job capturing the nerve-jangling excitement and ulcer-inducing tension that come with chasing a big, breaking story. One of the nicest grace notes in a book full of them comes after a close call, when Hurley realizes that he had “never come that close to death. But even more trying, he had never written so much on deadline.”

In the solipsistic media world, much time has been spent tittering about the real-life antecedents of characters like Edith Sawyer, a floundering former hotshot who had done “a stint in Latin America, where, rumor had it, she bedded an array of dictators and banana magnates, emerging pregnant with stories,” and Hickory Bosch, a disgraced former executive editor who “settled in an old saltbox cottage on the shore of Cape Fear, where he indulged his passion for clamming.” That manner of insider arcana shouldn’t intimidate the civilians out there; you don’t need to have spent a lifetime obsessed with media gossip to enjoy this any more than you need to know that Woody Allen was referencing Fellini’s Amarcord to appreciate the opening scenes of Annie Hall.

Black and White and Dead All Over is above everything else a page-turner, but there’s also a message contained therein. By the end of the book Darnton’s respect for the life-and-death power of the written word is readily apparent: a pilfered paragraph from War and Peace leads to one character’s downfall, the novel’s denouement is brought about by a couple of lines of Byron, and a crucial plot point stems from an epically clumsy lead paragraph.

This always-present subtext, along with Darnton’s palpable anxiety about the threats to modern journalism, brings him closer to the intent of his original task than it appears at first. Fittingly, his bittersweet nostalgia for a bygone era in journalism — one that Darnton and his father both embodied, in their own ways — is captured best in a toast offered up by Jimmy Pomegranate, a Falstaffian scribe with “the self-regard of Orson Welles” and a passport that’s been stamped in 182 countries:

“Here’s to us

“Who’s like us?

“Damned few

“And they’re all dead.”

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

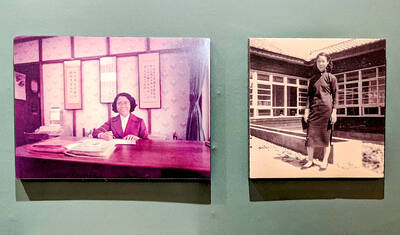

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in