In 1960, Tomi Ungerer was returning from his native France to New York City, his adopted home, when he realized that three men were walking uncomfortably close to him as he was leaving a terminal at the old Idlewild airport in Queens. One ordered him to drop his suitcases. Then the others latched onto him, hustled him into a car and drove him to a nearby building where they questioned him obliquely about his travel and his political affiliations.

“It was just like in a movie,” Ungerer recalled with a quiet laugh. “I don’t know whether it was the FBI or whoever they were. They even opened the soles of my shoes.”

It’s the kind of trench-coat caper that doesn’t generally feature a beloved children’s book author as the abductee. But then, few children’s book authors in those wary cold war years made a habit of playing poker with the Cuban envoy to the UN, as Ungerer did, or applied for a visa to visit China. Or had a side career publishing books of often disturbing erotica. Or held parties in the Hamptons so notorious that the neighbors were afraid to invite him to theirs.

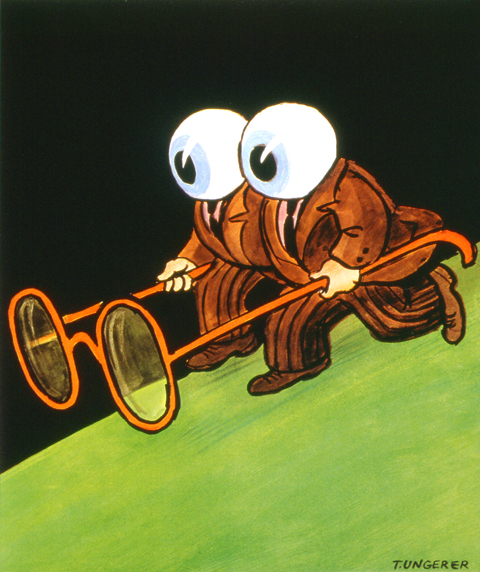

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Ungerer moved to New York from Strasbourg in 1956 — with only a trunk full of drawings and US$60 in his pocket, as articles from those years unfailingly report — and became an almost immediate success. At the dawn of a golden age for magazine illustration, the jazzy, acid-etched work that flowed from his chaotic studio on West 42nd Steet seemed to be everywhere: Esquire, Life, Harper’s Bazaar, the Village Voice, the New York Times.

His first children’s book, The Mellops Go Flying, about a family of daring French pigs, was published to glowing reviews in 1957, the same year he introduced his friend Shel Silverstein to Ursula Nordstrom, his editor, a legend in children’s books at Harper and Row, who would soon publish another of Ungerer’s friends, Maurice Sendak.

For many years Ungerer’s books were solidly in such classic company. “No one, I dare say, no one was as original,” Sendak said of him. “Tomi influenced everybody.”

But after he left New York, and the US, for good in 1970, his reputation seemed to depart with him. While his stature increased in Europe and Japan, his books began to fall out of print in the US, to the point that Phaidon Press, the London art-book publisher, could describe him recently — and fairly accurately — as “the most famous children’s book author you have never heard of.”

But Phaidon is hoping to change that. It has acquired the rights to almost all of Ungerer’s work and this fall will start to republish his children’s books in the US and the UK, beginning with The Three Robbers from 1962, a darkly drawn tale of big-hatted brigands and the orphan girl who shows them the error of their ways, a classic in France and Germany. Other titles will soon follow, like Emile, the story of a heroic octopus, and Moon Man, first published in 1967, tattered library copies of which can now turn up on used-book sites for more than US$100.

Though he has never been much out of it, the spotlight seems to be shining particularly brightly right now on Ungerer. The Three Robbers was recently made into an animated film whose US distribution rights have been bought by the Weinstein Co. Last fall a museum dedicated wholly to his work was opened in Strasbourg.

For the past three decades Ungerer, 76, has made his home there and in a tiny coastal village on the Mizen Peninsula in Ireland, about as far south on the island as a traveler can go. He describes himself as an Alsatian first and a European second, and has had a long love-hate relationship with the US, which nurtured him but ultimately alienated him. So there is an undercurrent of ambivalence in his voice when he talks about his coming reintroduction to American shelves.

He attributes his obsolescence here partly to absence, but more to a kind of leftover Puritanism that he said emerged when he began to branch out from straight-ahead advertising and editorial work to more polemical and personal art.His anti-Vietnam War posters, revered among graphic artists, pulled no punches. The best-known shows the Statue of Liberty being shoved into the gaping mouth of a yellow man by an arm emblazoned with the word “Eat.” Another shows a bomber pilot painting pictures of screaming babies on the nose of his jet.

But Ungerer said it was probably his other imagery for adults, his erotica (“not pornography, please,” he implored) that consigned him to the children’s book dustbin in the US. Especially after 1969, when he self-published a book of drawings ominously titled Fornicon — a nightmare vision of mechanized pleasure that owed more to the Marquis de Sade and Aldous Huxley than to Aubrey Beardsley or Playboy — children’s publishers began to shun him, and libraries began to stop carrying his books, he said.

“Americans cannot accept that a children’s book author should do erotic work or erotic satire,” he said in a recent telephone interview from Ireland, which he interrupted occasionally to tend to a dog or roll a cigarette. “Even in New York it just wasn’t acceptable.” (Perennial suspicions that he was a Communist — which he says he was not — didn’t help.)

Amanda Renshaw, Phaidon’s editorial director, said even among children’s authors with darker themes and side careers writing for grown-ups, like Sendak or Silverstein, Ungerer remained a kind of renegade. “He’s an adult who’s interested in sex and politics and also someone who’s immensely talented at telling stories for children,” she said. “And the fact that he’s open and honest about everything has really gone against him. I think people just aren’t used to children’s book authors being that honest.”

Ungerer and his third wife, Yvonne, an American whom he met in New York, spend most of their time in Ireland, where they raised three children (Ungerer has a daughter from a previous marriage) and are viewed as honorary citizens. Though a bit frail these days and not able to travel as much as he would like, Ungerer is still prolific and is at work on a memoir about his days in New York, which will follow an earlier one about years spent in rural Nova Scotia and Tomi: A Childhood Under the Nazis, about witnessing the German occupation in Alsace as a boy.

At the beginning of his career in New York, when children’s books tended toward the treacly, he said he knew he wanted to try to reach children on a more fundamental level. “I think children have to be respected,” he said. “They understand the world, in their way. They understand adult language. There should not be a limit of vocabulary. In The Three Robbers I don’t use the word ‘gun.’ I say ‘blunderbuss.’ My goodness, isn’t it more poetic?”

Burton Pike, a professor emeritus of comparative literature at the City University of New York Graduate Center who became friends with Ungerer in the 1950s, said: “He’s never lost the feeling of how a child sees the world. And a child’s view is not really sentimental.”

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world

Through art and storytelling, La Benida Hui empowers children to become environmental heroes, using everything from SpongeBob to microorganisms to reimagine their relationship with nature. “I tell the students that they have superpowers. It needs to be emphasized that their choices can make a difference,” says Hui, an environmental artist and education specialist. For her second year as Badou Elementary’s artist in residence, Hui leads creative lessons on environmental protection, where students reflect on their relationship with nature and transform beach waste into artworks. Standing in lush green hills overlooking the ocean with land extending into the intertidal zone, the school in Keelung