Tabla drums warbled and lights beat down as the woman glided down the runway, her sari billowing loosely and her hair pulled tight. As fashion shows go, the sashay-spin-repeat sequence was fairly routine.

But the background of many of the models at this event on a Wednesday evening last month, held in a fourth-floor dining room at the UN, was anything but.

Known as Dalits, or “untouchables,” the women have such a low social standing in their native India that they are below the lowest rung of the officially banned but still-present caste system.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

In fact, this particular group of women — 17 on stage, an additional 20 or so in the audience, all with dresses that were pool blue, to honor the official shade of the UN — once cleaned septic systems for a living.

For those who imagine that the indelicate task can somehow be pulled off by sticking a hose from a truck into a tank in the ground, guess again.

Using straw brushes, these women, called scavengers, would hand-sweep the contents of often-dry latrines into bamboo baskets, then cart away the results on their heads.

Reviled to the point where others would let them die in the streets rather than brush their skin, according to event organizers, theirs was a grimy and dangerous existence that would make a Dickensian lifestyle, in contrast, an improvement.

“Gandhi had a wish to make a scavenger the president of India,” said Bindeshwar Pathak, a New Delhi businessman, at a panel discussion that took place before the event in an auditorium lined with ash wood.

Pathak, who is the head of an international company that manufactures flush-style private and public toilets, has also built four clinics across India to teach scavengers — there are an estimated 500,000 among the 160 million Dalits who make up 16 percent of the country’s population — basic hygiene, literacy and job skills, to better their fates.

Indeed, Wednesday’s fashion show was partly a tribute to Pathak from the UN Development Program, which in a 156-page report released on Tuesday praised his for-profit, private-sector solution to an intractable social problem.

“Giving them this opportunity shows the world that scavengers are equal to everybody else,” Pathak said.

The former scavengers, none of whom had traveled outside India before, also seemed to help publicize what the UN has decreed the International Year of Sanitation.

This effort (earlier ones focused on peace and on microcredit) is to reduce by half the 2.4 billion people who drink and bathe in dirty water by 2015, though with just 300,000 aided so far, progress has admittedly been slow.

“It’s a huge undertaking,” said Vijay Nambiar, chief of staff to Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary-general, at the panel discussion.

“But,” he continued, “we must raise awareness of sanitation with special attention to the privacy, dignity and security of women.”

Though the message was somber, the mood turned light after guests adjourned to the Delegates Dining Room, which provided views of a twinkling Queens.

Waiters in tuxedos balanced platters of wedge-shaped samosas by tables of saffron chicken and lentil salad.

On the nearby 15m runway, the former scavengers strutted side by side with more conventional models, whose bobbed hairdos and heavy makeup balanced bright gold, pink and green chiffon gowns.

Some in the 175-person crowd leaped at the chance to meet Pathak, whose social service may be as admired as his entrepreneurial talent.

Although his net worth has not been widely reported, his company, Sulabh International, made a profit of US$5 million in 2005, according to the UN report, which is a Bill Gates-level sum in an impoverished nation.

Much of that revenue presumably came from Sulabh’s numerous public pay toilets, which are also found in Ethiopia, Madagascar and Afghanistan; Pathak also runs a popular New Delhi toilet museum.

“I’m here because I think what he’s done is remarkable,” said Anjali Sud, 24, of Manhattan, who works for a magazine publishing company but volunteers at the UN in her spare time.

As she spoke, her sister Anisha Sud, 21, passed a pen to Pathak for an autograph.

Fawning, too, was Virender Yadav, 54, a New Delhi native who now lives in Richmond Hill, Queens, and whose arms were piled high with free brochures and books.

“This is very unusual,” Yadav said, adding, “I was very surprised” to learn that former scavengers would be in New York City.

“I am so glad they are bringing them up in the world,” he said.

The culture shock was not lost on the former scavengers, either, such as Usha Chaumar, 34, who wore bangles on her wrists and a glittering bindi on her forehead.

Like her fellow travelers, Chaumar comes from Alwar, a city in Gujarat state, and like the others, she was married young, at 14, though her husband is now dead.

“All my friends and relatives need to get better jobs,” she said through a Hindi interpreter, “so they can come into the mainstream.”

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

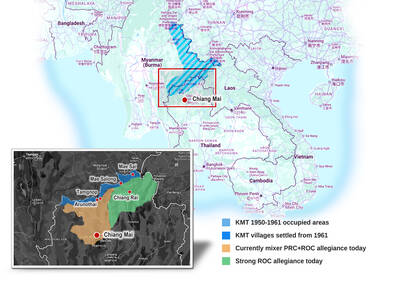

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers