It's not until 25 pages into Guantanamo that the trussed-up, abused body with whose agonies and discomforts we've become intimately familiar is finally granted the dignity of a name. "He falls on his side, knees free, his head in the gravel. He is here. He's arrived at last. Somewhere on earth, a prisoner, I, Rashid."

In a former life, Rashid, a young man from Hamburg, set off to visit his grandmother in Delhi, armed only with a Lonely Planet guide. By the time Dorothea Dieckmann’s extraordinary novel locates him, he’s been seized by the US military, transported to Camp X-Ray on Guantanamo Bay, bound, hooded, caged and systematically humiliated. His grip on his old identity weakens with frightening speed as his new life is dominated by physical distress, stimulus deprivation and the urgent need to somehow please his captors. “He doesn’t dare move. He must wait, breathe, wait, breathe. His weight is poorly distributed, and from weight comes pain, meaning the pain is poorly distributed, as well. There’s too much pain in his knees, too little in his feet. Just don’t move. His feet hurt, but his knees hurt more ... It’s a decisive struggle: shift the weight, yes or no, distribute the pain, yes or no. The battle intensifies but neither side is winning.” This desperate, ineffectual accommodation with enforced frailty is just one of many lessons Rashid will learn, all of them underscoring the same conclusion: nothing you do or say can help you.

Guantanamo has received unanimous praise, although the language of that praise is unlikely to inspire the average reader with puppyish enthusiasm: “an unforgiving read,” “harrowing,” “scouringly brutal.” Without meaning to, such phrases imply that Guantanamo is the epitome of the Grimly Serious Literary Novel. While Dieckmann admittedly disdains any imperative to provide entertainment, it would be unfair to conclude that she doesn’t care about her readers. The book’s structure — six episodes at different stages of Rashid’s imprisonment — is designed to allow us precisely the sense of forward momentum the camp’s inmates are denied. We live in Rashid’s skin and appreciate that his torment drags on unremittingly, but, in the spaces between chapters, we snatch a breath of relief. A mere 150 pages in length, the book is a finely judged balance of art and anguish: we learn what it’s like to be trapped in mind-numbing detention, without feeling we are being detained by a mind-numbing novel.

Dieckmann understands the impulsive vagueness of young men’s adventures, the way a 20-year-old can end up lying face-down in the mud after an anti-American demonstration near the Afghanistan border, and it’s nothing to do with politics, but rather with climbing the Himalayas, male bonding, keeping one’s leisure options open, enjoying one’s final vacation day in exotic Peshawar. Or so it seems. As Rashid’s interrogators torment him more and more, the hazy naivety of his agenda in Pakistan seems less and less credible to him; his story disintegrates, reassembles, incorporates feeble lies, half-remembered impressions, guilty dreams. At no stage is the outside world permitted to restore some semblance of an objective perspective: we are trapped inside Rashid’s increasingly diminished consciousness. One of Dieckmann’s masterstrokes is that we don’t hear the questions Rashid’s interrogators fire at him, only his responses, sometimes befuddled, sometimes clear, but always ignored. After many months in Guantanamo, Rashid realizes that “it wasn’t anybody’s job to release prisoners — that there was no plan, not even a secret one.”

Discussing a subject as important as institutionalized torture, it seems trivial to mention typesetting glitches and lapsed editorial standards. But one of the wisest insights in Guantanamo is how ill-equipped the human mind is to focus on big questions and ideological abstracts. Rashid’s world is not one of Islamic extremism versus the West, but defined by small things: his water bucket, his toilet bucket, his washcloth, his blue plastic blanket, his soap and so on. The US army chaplain even gives him a Koran to read, a belated, lamentably misguided concession to what his oppressors imagine constitutes human rights. Dieckmann’s potently empathetic novel shows more clearly than any amount of CNN footage that the battle continues, but neither side is winning.

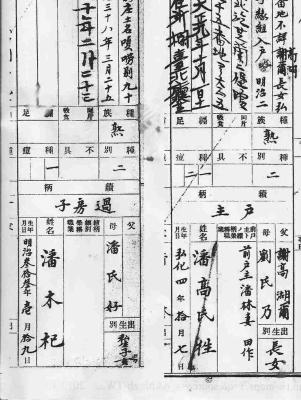

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in