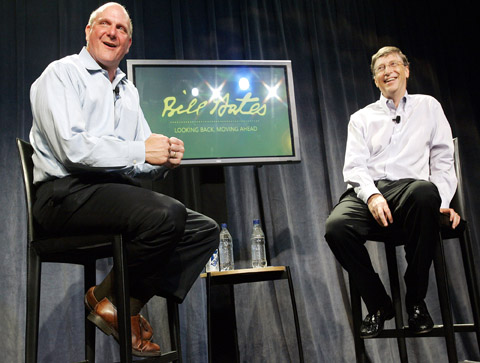

Despite his role as chief executive at one of the most influential companies in the world, Steve Ballmer is relatively unknown outside the technology industry — having always been eclipsed in the public eye by one of his oldest friends, Bill Gates. But when Gates stepped out of his Microsoft office for the last time on Friday, leaving the company in the hands of his former college buddy, the 52-year-old Ballmer stepped out of his shadow.

Given his bombastic style and imposing physique — he stands 1.83m tall and carries the broad, bone-breaking stature of a retired American football player — it is unlikely that Ballmer will find trouble making his mark.

He is well known for his boundless excitement — which often explodes dramatically — and retains an unquenchable enthusiasm for the software company he joined 28 years ago.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

The clearest insight into the mind of the 63rd richest man in the world is probably a single, minute-long piece of video that shows Ballmer on stage at an internal Microsoft event, skipping around like a dervish. He screams, yelps and caterwauls, before stopping to shout “I love this company!” His bizarre dancing — more pumped-up sports coach than corporate executive — is now as much part of his legend as his notoriously quick temper.

Microsoft employees — who would talk only on condition of anonymity — describe how Ballmer can become excessively angry in meetings, the most famous example being when one member of staff, Mark Lucovsky, told his boss he was quitting to join Google.

In a sworn affidavit to a US court, Lucovsky described how Ballmer responded by throwing a chair across the room and shouting: “Fucking Eric Schmidt [chief executive of Google] is a fucking pussy. I’m going to fucking bury that guy. I’ve done it before, and I will do it again: I’m going to fucking kill Google.”

PHOTO: AFP

He might be quick to anger, but those who know him describe Ballmer as quick, mathematically gifted and intense. His background is all-American: born in the affluent suburbs of Detroit, his father was a manager at Ford who sent his son to Harvard.

It was there that he became friends with Gates; the pair lived down the hall from each other and shared an interest in mathematics. While Gates dropped out to found Microsoft in 1975 — famously stating that the college had nothing more to teach him — Ballmer went on to graduate and then joined Procter & Gamble as a product manager.

Shortly after returning to college to study business at Stanford University, however, Ballmer was recruited by his old friend. After joining Microsoft in 1980 as the company’s 24th employee he worked on assignments around the US and Europe.

Such dedication was rewarded, and Ballmer quickly became Gates’s go-to guy, making up for his lack of technical expertise with passion and commitment to the cause. Over the next 20 years he commanded various company divisions, before rising to president in 1998 and then, in 2000, CEO.

“Loyalty is Ballmer’s number one strength,” says Fredric Alan Maxwell, who wrote the unauthorized 2002 biography Bad Boy Ballmer: The Man Who Rules Microsoft. “If Ballmer were your friend, he’d be the best friend that you ever had. His loyalty is one of the reasons he still drives Ford cars — his father worked there.”

Those who have worked with him describe his management style as “macho” and “intimidating,” and for good reason: he tore his vocal cords at one meeting after shouting too much.

Lyndsay Williams, a former engineer at Microsoft’s Cambridge Research Center in the UK who has met Ballmer several times, described their first meeting.

“He shook my hand and it felt like he had crushed every bone,” she said. “I found it a bit overpowering — after all, it’s not a power struggle.”

Whether or not he is the archetypal alpha male, such examples of his infamous bullish machismo seem to have characterized Ballmer’s command of the company since he became chief executive. Critics focus on Microsoft’s history of anti-competitive practices, while insiders remain concerned about its stalling share price and lack of vision. The recent attempt to buy Yahoo, which carried a sense of both desperation and intimidation, has led many to wonder publicly whether Ballmer is the right man for the job.

The fear, say those familiar with the company, is that after a decade-long transition of power from Gates, Ballmer is in danger of being stuck in the past. And even though younger rivals such as Google are outflanking the Seattle software giant, Ballmer cannot stop himself trying to stay top dog.

“Ballmer simply doesn’t like to lose. At all,” said Maxwell. “He’s a competition addict. Or, as one of his Harvard classmates told me, when his competition switch was turned on, it then broke.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of