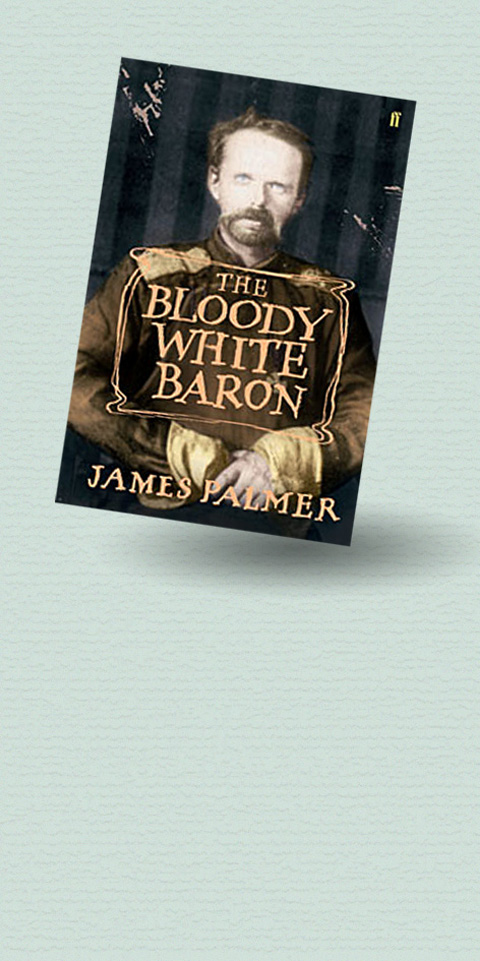

Usually, when a biographer has failed to find sources that take the reader inside the head of his subject, it is a disappointment. In the case of Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg, however, one can only feel intensely relieved that James Palmer has been unable to come up with an intimate diary, a memoir from a mistress or letter home to Mom. For Ungern appears to have been so unpleasantly mad (think keeping people up trees for days at a time or sending them on patrol naked on the Siberian ice) that in any other era he would have been committed to a genteel asylum somewhere in a foresty bit of middle Europe where his fantasy that he was the reincarnation of Genghis Khan would have been tolerated with a wry smile and a very large bunch of keys.

Ungern didn’t start out mad, although he does seem to have been really quite bad from the get-go. Born in 1885 into one of those aristocratic Baltic German clans that had staffed the imperial Russian court and army for centuries, Ungern was expelled from pretty much every elite educational and training institution open to him. Still, he managed to creep into the Russian army in order to serve in the Russo-Japanese conflict of 1904, and from there he levered himself a spot as a cavalry general in World War I, which followed shortly after.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 Ungern joined the Whites in the Far East and served under the equally bonkers Semenov, who by now had the backing of, confusingly, the Japanese. Appointed governor of the Siberian town of Dauria, and no longer considering himself beholden to anyone, Ungern set about creating a private army consisting of 16 nationalities, including Cossacks and plain old Russians. The objectives of this raggle-taggle crew were to restore the late Tsar’s brother to the imperial throne, recreate the glory days of Genghis Khan’s empire, and uphold the rule of the living god-king, Bogd Khan, in Mongolia.

This last ambition was key. For underpinning Ungern’s program was a fanatically held belief in Buddhism. And, in case that sounds like a massive contradiction, Palmer is on hand to remind us that Buddhism, especially in its Tibetan and Mongolian guises, has always been as politically dirty as any other world religion. Far from being a charter for godless, rational serenity, the kind of Buddhism in which Ungern believed was a war-mongering pantheism with peaks of refined cruelty. Even the Dalai Lama of the time turns out to have been a baddy.

This license to be mean came in handy in 1921, when Ungern and his army stormed into Mongolia and declared it an independent kingdom under his sole and absolute rule. Anyone who got in his way — members of the deposed Chinese administration, stray Bolsheviks, anyone who could conceivably be Jewish — met with the kind of medieval cruelty of which Genghis himself would have approved. Tricked out in Mongolian costume (which reminded everyone else of a bright yellow dressing-gown), Ungern routinely flogged people to death, hanged lamas and did nothing to stop one of his soldiers indulging in his speciality of seizing old ladies off the street and choking them to death. Ungern’s earlier mental instability — fellow officers had wondered at his suicidal bravery on the battlefield during the eastern campaigns of the World War I — now blossomed into outright psychosis.

Palmer’s book is, in truth, probably one for the boys, or at least for people good at remembering who is fighting whom and why at any particular moment. If you’re not that way inclined, there are still plenty of “horrid history” moments to keep you enthralled — for instance, the fact that the baron’s men were great advocates of “the eternal boot,” whereby a soldier took the skin of a freshly killed animal, wrapped it around his foot and let it harden. Specialists will know that Ungern’s story has been told several times before, but newcomers will surely find it startling to learn that at least a decade before Hitler came to power, there was already a European leader whose adherence to a mix of sloppy religiosity, historical determinism and half-baked racialism was in danger of getting him far further than any sane person could possibly have predicted.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of