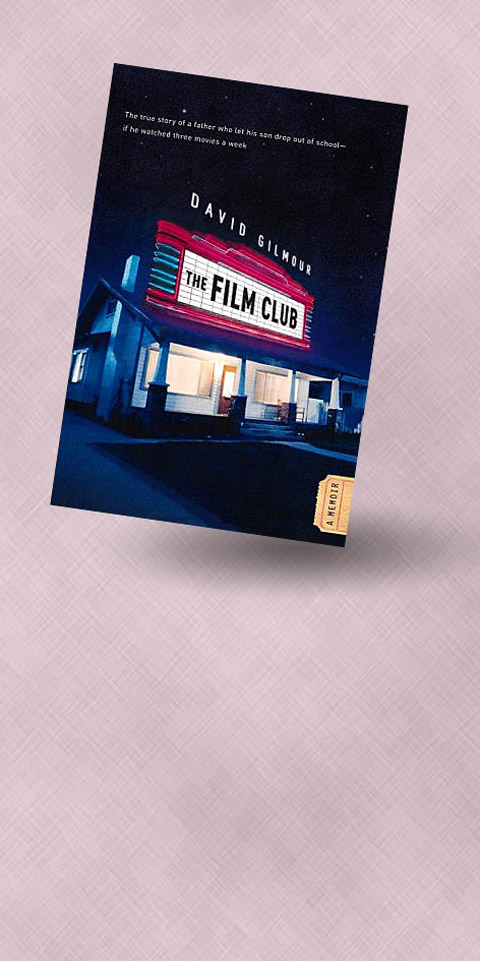

If your teenager was cutting classes, failing at school and on his way to becoming a juvey James Dean, what would you do? When Canadian film critic and novelist David Gilmour saw that outline forming with his 15-year-old son Jesse, he came up with a solution that could be viewed as brave or foolish:

He let Jesse drop out of school.

He didn’t make him get a job.

And he let him live at home for free.

On two conditions. No. 1: No drugs. No. 2: He had to watch three DVDs a week with his dad.

And so begins The Film Club, Gilmour’s unexpectedly delicate memoir of a relationship that jells over screenings of On The Waterfront, Chungking Express and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Here is a story about a father and son sitting on their living-room couch watching movies, talking a bit and watching more movies. But Gilmour’s book isn’t really about the movies, although there is a lot of movie commentary in it.

It’s about how father and son discover each other at a time when most parents are shut out from their children’s lives. We are exposed to Jesse’s deepest, most painful feelings, everything from free-floating teen insecurities to darker fears about a young man’s attractiveness to women.

Gilmour is good with little observations that tell larger truths, such as the way Jesse slams back a drink. Instantly, his father sees how Jesse parties when he’s with his friends, and it reveals something about his son’s vulnerabilities.

Gilmour is upfront about himself, as well: He is thrice-married and going through a fallow career spell (ie, unemployed). So it adds another rich layer to the book that he is facing his own doubts as he tries to shore up Jesse’s.

The Film Club won’t be revelatory to any serious students of film. But Gilmour does make some interesting observations, such as this one on Woody Allen: “There’s a sort of rushed homework feel to Woody Allen’s movies these days, as if he’s trying to get them finished and out of the way so he can move on to something else. That something else, distressingly, is another movie.” Exactly.

The movies, of course, are mere backstory for a magic interlude between father and son. As the book unfolds, you see that Gilmour’s boldest tactic is to simply treat Jesse as a grown-up, man-to-man. His advice on women is sagacious, and clearly hard-won:

“Getting over a woman has its own timetable, Jesse. It’s like growing your fingernails. You can do anything you want, pills, other girls, go to the gym, don’t go to the gym, drink, don’t drink, it doesn’t seem to matter. You don’t get to the other side one second faster.”

Predictably, the late teen years are a minefield. There is a bad night of cocaine with a guy named Choo-Choo. And Jesse goes through endless relationship hell with an unforgettable heartbreaker named Rebecca Ng.

Gilmour recalls his own rough passage, including a beautiful memory about hardly noticing an ex-lover on a train. He realizes that the most painful part of being a parent is letting Jesse sort out things on his own, especially women.

Does he succeed? Well, at memoir’s end, Jesse is interested in college, can namecheck several French nouvelle vague movies and brings up, without prompting, the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. They’ve watched everything from Ran and La Dolce Vita to Rocky III and Showgirls.

Not a traditional education, per se, but not the worst one you can imagine, either.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

Artifacts found at archeological sites in France and Spain along the Bay of Biscay shoreline show that humans have been crafting tools from whale bones since more than 20,000 years ago, illustrating anew the resourcefulness of prehistoric people. The tools, primarily hunting implements such as projectile points, were fashioned from the bones of at least five species of large whales, the researchers said. Bones from sperm whales were the most abundant, followed by fin whales, gray whales, right or bowhead whales — two species indistinguishable with the analytical method used in the study — and blue whales. With seafaring capabilities by humans