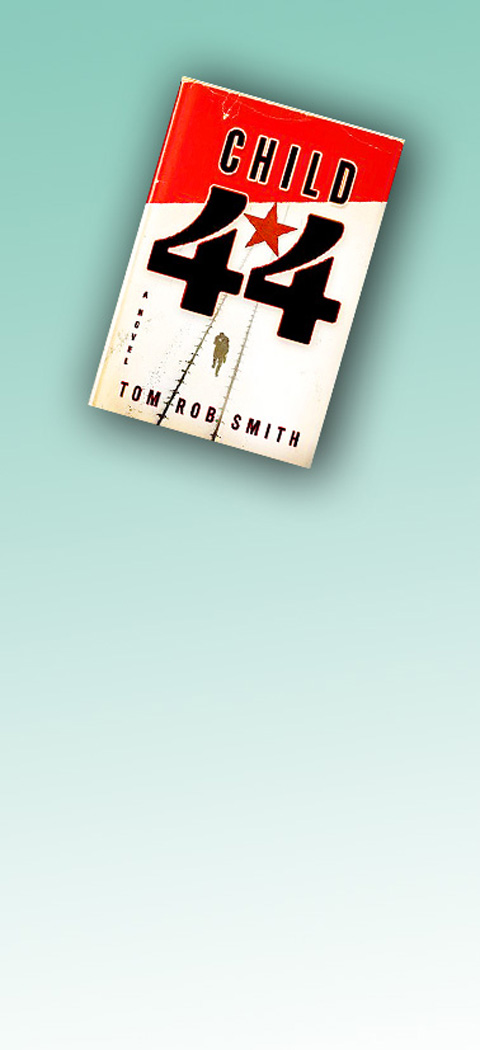

British novelist Tom Rob Smith’s Child 44 balances on a tricky Catch-22.

It is 1953, the final days of Stalinist terror in the USSR, and Leo Stepanovich Demidov, a decorated World War II hero who has successfully made the transition to the MGB, the State Security Force (and predecessor of the KGB), has stumbled onto a serial killer.

The catch is, there is no crime in a communist state. That would be calling into question “one of the fundamental pillars” of society, that there is no need or want when all is provided for. Murder tarnishes everyone.

Leo, whose loyalty to his country is severely tested but never quite broken over the course of this immensely entertaining debut novel, gradually realizes that “the killer would continue to kill, concealed not by any masterful brilliance but by his country’s refusal to even admit that such a man existed, wrapping him in perfect immunity.”

It’s a fascinating premise. And yet Smith, a 30-year-old screenwriter who received a million-US dollar advance for this, his first novel, has produced a page-turner that is more memorable for its atmosphere — the dismal living conditions, the rotten food, the backbreaking work schedules, the inexorable weather (How do these people endure the weather?) and, most of all, the suffocating paranoia continuously stoked by twisted Soviet logic — than for its grace or eloquence as a detective thriller. (The book has been blessed by director Ridley Scott, who bought the film rights.)

In fact, Smith, whose screen credits include a Cambodian soap opera, handles the whodunit rather ham-fistedly. The killer’s modus operandi is foreshadowed in the first chapter, and we quickly realize who the killer is, once the bodies start turning up, many of them preserved in the snow, their stomachs removed as if by a clumsy surgeon, their mouths stuffed with bits of tree bark, a length of twine tied round an ankle.

Based loosely on the sordid crimes of Soviet serial killer Andrei Chikatilo, the horrible thing is these victims are children.

But Smith’s aim is not to keep the reader guessing about the killer’s identity. Rather, it is to leave us unbalanced, completely off-kilter, not knowing where to turn next or whom to trust. In other words, Smith puts us in Leo’s shabby shoes.

See, you have to get into the Soviet mind-set. Comrade, you are encouraged, no, required, to spy on and inform us of the activities of your co-workers, friends and family — even your father, your sister, your wife — about any deed or word that might be critical of the country. Of course, simply questioning someone’s loyalty makes them guilty, and if they are guilty, why are you associating with them?

“The duty of an investigator,” Leo knew, “was to scratch away at innocence until guilt was uncovered.”

But Leo — “no longer a lackey who merely followed orders” — becomes a little too sure of himself and is therefore vulnerable because “paranoia was an essential asset, a virtue which should be trained and cultivated.”

In a tidy bit of cruelty, Leo’s superiors hand him his next assignment. He must investigate his wife, who is suspected of spying. He can renounce her, saving himself and his aging parents. Or he can stand by her.

It is this test of loyalty, concocted by Leo’s nemesis and second-in-command, Vasili, who has every reason to want to see his squad leader demoted, humiliated and executed, that is the true heart of Child 44.

Leo makes the right decision.

But the story breaks down in an unimaginative ending, given the fact that some prisoners at the MGB’s Lubyanka prison, to cite one form of torture, are stripped and placed in coffinlike closets where bedbugs had been left to multiply. They quickly confess to anything.

Overall, however, Smith has done a remarkable job of submerging us in a time and place that “didn’t need poets, philosophers and priests.” Instead, “it needed productivity that could be measured and quantified, success that could be timed with a stopwatch.” Even if the commodity being measured was human beings.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the