What do reality TV shows like Survivor and America's Next Top Model have in common with an insurgent method of stimulating useful innovations around the world?

It may be hard to believe that watching Tyra Banks drive aspiring models to the breaking point can provide insight into how to accelerate technological change.

Well, pinch yourself.

PHOTO : NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Popular reality shows indeed provide a way to understand the logic behind a new wave of contests in technological innovation. Both types are driven by head-to-head competition among unknowns. And the winner takes all - and is celebrated in the process.

A research agency for the government is using the model to spawn a new generation of driverless cars. Google is sponsoring a US$20-million-grand-prize race to the moon and back for commercially feasible spacecraft.

And this week, the newest contest - for a drivable, affordable car that gets 42.51km per liter - will be formally started at the New York International Auto Show. Sponsored by the X Prize Foundation, which is also running the lunar contest, the car contest is really two in one. In 2010, there will be a winner in the "city" category, which permits three-wheelers, and another in a category for four-wheel, four-seat cars.

"Human beings do some of our best work under the pressure of competition," says Peter Diamandis, chairman of the X Prize Foundation, based in Santa Monica, California, "Cooperation is wonderful, but it doesn't lend to breakthroughs or true innovations."

The usual way that companies spawn advances is to employ staff members or contractors to create them. The market then rewards the winning products. The problem, however, is that the market sometimes delivers just incremental improvements, especially in areas of energy, transportation and health. Breakthroughs are imagined, but not mass-produced.

Contests, which come with a deadline, aim to create a sense of urgency, conjuring up a "race" mind-set that harks back to the Cold War. After World War II, competition between the US and the Soviet Union fostered technological races in space and weapons, for instance. In 1927, Charles Lindbergh made aviation history winning a US$25,000 prize for being the first pilot to fly nonstop between New York and Paris.

Why have contests proliferated in recent years? "Tycoons have come into it," says Stewart Brand, president of the Long Now Foundation, which aims to raise awareness on solving long-term technological problems. The X-Prizes, for instance, are funded by such wealthy people as Elon Musk, a co-founder of PayPal, and Stewart Blusson, a Canadian who made a fortune in diamonds.

The sponsor rewards only the winner. The contestants invest their own money, thus expanding the pool of capital devoted to the field. Taking a page from the playbook of professional sports, contestants can often attract sponsorships.

Skeptics say that prizes often merely confirm what has already been done in the lab - and that too often they shower attention on the contest's founders.

"Creating useful innovations ought to be self-rewarding," says Robert Friedel, a historian of technology at the University of Maryland.

Although the contests have flaws, they bring innovators into the open. That can inspire young inventors - and tip off venture capitalists to the next big thing. Indeed, venture capitalists watch these contests to get leads on whom to fund.

"These contests and prizes become a quality-control mechanism," says Yogen Dalal, a managing director of the Mayfield Fund, a venture capital firm in Menlo Park, California.

To be sure, the devil is in the details. The creation of a great contest echoes the lesson of the Goldilocks story: Make the goal not too difficult, but not too easy.

As more innovation contests are introduced, the more obvious goals may already be met. For instance, there is already an all-electric car made by Tesla Motors of San Carlos, California - going into production Monday - that promises to achieve more than 42.51km per liter. But the Tesla car is only a two-seater.

The complexities of creating the auto prize illustrate a wider problem of how to come up with ever more novel tests of human ingenuity over time. Brand of the Long Now Foundation predicts that contests will soon pursue "things we truly think of as impossible."

Brand's wish list includes machines that defy gravity or that allow us to read the minds of other people.

Hey, Tyra Banks, are you available for an afternoon of Vulcan mind-melding?

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

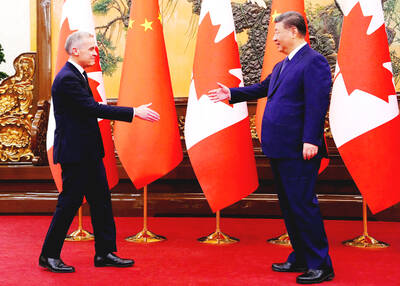

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director