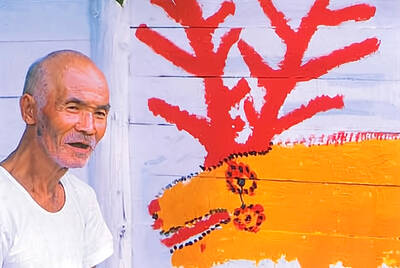

Ominataro (朱秀春) slouches in his chair and stares at the blank projector screen in front of him in this 100-seat auditorium on a recent Saturday morning in a community hall in Ta-ai (大隘村), Hsinchu County. The sun shines on the village - nestled amongst dense vegetation at the bottom of a mountain range. He says an occasional word to the man sitting beside him, but otherwise concentrates on the white space in front of him.

A year earlier, the scene outside the hall was radically different from the subdued atmosphere today. At that time, more than 2,000 Aboriginal people from the Saisiat (賽夏) tribe gathered to celebrate the Pasta'ay Grand Ceremony (巴斯達隘10年大祭), a harvest ritual occurring every 10 years on the 15th day of the 10th lunar month that involves four days of dancing, chanting, singing and feasting. Its reputation was such that, according to Ominataro, 67, "There were so many people at the ceremony you couldn't even hear the songs being chanted. … We were happy, though, that our ritual garnered so much attention from outsiders."

Today, the assembled elders have arrived to watch Pasta'ay: The Saisiat Ceremony in 1936 (巴斯達隘: 1936年的賽夏祭典), a documentary of the rite filmed by Nobuto Miyamoto, a Japanese anthropologist working at the then Taipei Imperial University (now National Taiwan University, NTU). Lost in the dusty archives of an NTU storeroom for almost 60 years, the film was rediscovered in 1994, restored and first shown at last year's Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival (TIEFF, 台灣國際民族誌影展).

Photos courtesy of the Department of Anthropology, NTU

The documentary's history is intertwined with the tribe's struggle to maintain an important event in the face of Japan's cultural homogenization agenda, the policies of which forced the island's people - both Taiwanese and Aboriginal - to give up their own culture and language in favor of Japan's. Its filming also provides a close-up look at how the Saisiat celebrated the rite 70 years ago - and how little it has changed over time.

Saisiat resist oppression

Unlike other documentaries filmed during the 50 years of Japanese colonization - which Hu Tai-li (胡台麗), a research fellow at the Academia Sinica's Institute of Ethnology says were usually propaganda films glorifying Japan's achievements - Pasta'ay: The Saisiat Ceremony in 1936 was made because the Saisiat wanted to show local Japanese authorities how important the festival was to the tribe.

"[The Saisiat] invited the anthropologists because the local county government planned to stop the ritual in the 1930s," said Hu Chia-yu (胡家瑜), an associate professor of anthropology at NTU who has done research on the Saisiat.

"The [Japanese] government forbade [different settlements] from getting together because they were afraid that indigenous people [would] revolt," she said. "A lot of [Aboriginal] rituals stopped at that time."

With memories of the Beipu (北埔) Incident, a Saisiat uprising in 1907, fresh in their minds, the Japanese had good reason - from a colonial mindset at least - to fear that plans for another revolt could be hatched at one of these gatherings.

"The head of a Saisiat village knew the Japanese were planning to stamp out the ritual so the tribe acted very quickly and organized a clan meeting," Hu said. "If the Japanese government tried to stop the ritual, they would have revolted again."

The Saisiat hold the Pasta'ay ceremony in reverence to the Short Black People (矮靈祭) - a legendary pygmy race that passed to the Saisiat their knowledge of agriculture, medicine, rice wine making and folklore. Much of this knowledge was given in the form of songs and dances, which the Saisiat believe they must perform, or they themselves will perish.

After making the documentary, Miyamoto used the film to convince the local Japanese magistrate that the event was a necessary part of Saisiat culture and canceling it would only cause headaches for the authorities.

Hu says that after the Japanese authorities saw the documentary, they arrived at a compromise with the tribe: Rather than canceling the ceremony, which at the time occurred annually with a grand ceremony held every 10 years, they agreed that the tribe's northern and southern ritual groups could individually celebrate the Pasta'ay biannually and together once every 10 years.

Standing firm for the future

Back in the community center, silence falls in the auditorium as the silent documentary begins. Then murmuring can be heard and members of the audience begin to shout out the names of people in the documentary who they recognize. At the conclusion of roughly 15 minutes of footage, the elders demand to see it again because the images appeared too fleetingly across the screen to determine people and places.

At the end of the second showing, which took considerably longer than the first because the elders kept calling on the assistants to slow the projection down, the assembled elders stood to give their impressions.

Noting the similarities between the celebration that took place 70 years ago and the one last year, Mamavale, also a Saisiat elder, says, "This documentary shows that, like food, the Saisiat are capable of preserving that which gives Aboriginal people nourishment. Where other tribes discard the fruits of their harvest, the Saisiat retain the riches from the ground. Other Aboriginal people change their rituals, only the Saisiat preserve them."

Though Mamavale's view may be an exaggeration, the tribe did maintain an important rite in the face of colonizing powers determined to stamp it out.

After the screening, Hu, who is encouraging Aboriginal people to take a more active role in their cultural preservation, hands out DVDs of the documentary to tribal elders.

TIEFF last year used Indigenous Voices as its central theme and encouraged Aboriginal peoples to speak out in their own voices. The topic of that festival prompted Aboriginal groups from around the world to change from being the subjects of documentary filmmaking to recording their own stories.

Another elder stands up and says, "Before, the history of the Saisiat was written by other people. After watching this documentary, I hope the Saisiat people can encourage each other to write their own history."

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a