At a press-conference in Taipei last week, Ang Lee (李安) appeared the most self-effacing and generous-natured of celebrities, but also one of the most intelligent. He guessed he was "not a macho kind of guy," he said, but was instead interested in outsiders, those who suffered from the conflicts of others, and especially women. He was also devoted to diversity, he said, to making each new movie as unlike the one that went before it as possible.

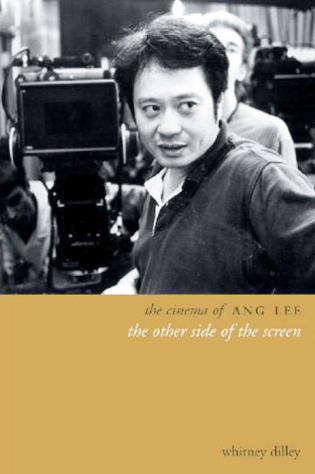

These themes and more are explored in a superb new book, The Cinema of Ang Lee. The author, Whitney Crothers Dilley, teaches English at Taipei's Shih Hsin University, and her account appears in the Directors' Cuts series from London's Wallflower Press. Taiwan is very fortunate to have someone of this quality teaching here.

This new book's essential characteristics are clarity, perceptiveness, sympathy and thoroughness. This is no coterie text for cineasts or crabbed work for academics. Instead, it's eminently clear-headed and lucid, covering all his films in detail, but also containing a perceptive and even profound overview of the inner nature of Lee's achievement.

In the author's view, Lee is on the edge of becoming - indeed, may already have become - one of the great film directors. But, as with Bergman or Fellini (directors she only refers to in passing as influences cited by Lee himself), his achievements have been on his own terms. He doesn't make movies on the orders of media moguls, but instead follows his own insights, so that each new creation is, in a sense, unexpected. Such people are best seen as major world artists who, as if by chance, have wandered into the world of film.

The diversity of Lee's oeuvre has been much remarked on. He has darted from East to West and back again, and then from one Western genre to another (after Lust, Caution (色,戒), his Asian movies are also coming to appear enormously varied). He not only makes films following his inner compulsions - he also makes them out of a sheer delight in the challenges and technical difficulties they pose. (Shakespeare's plays were also astonishingly varied in subject matter and unpredictable in style).

Lee's films are full of risk, the author claims, courting failure (and once, in the case of Hulk, discovering it). They are also free of stereotypes, filled instead with a desire to make appear normal the kinds of people who are usually considered outsiders. This she puts down to Lee's ambiguous position as an immigrant from Taiwan living and working in the US - half celebrity, but also half outsider.

One of the book's arguments is that Lee brings specifically Chinese qualities even to his American movies. The characteristics it pinpoints are a rejection of the standard Hollywood "happy ending," and a related sadness that life in reality is not what you dream it could have been. This melancholic nostalgia, the author points out, is very characteristic of traditional lyric poetry in Chinese, but it also pervades Lee's films all the way from Pushing Hands (推手) to Lust, Caution.

She also points to the power of silence in Lee's films. The focus on the plight of the individual that this silence leads to is exactly what Lee wants to achieve. As the British poet Wilfred Owen wrote about his World War I subjects, the poetry is in the pity. And so it is with Lee.

In an interesting aside on The Wedding Banquet (喜宴), Dilley remarks that the script originally had a leading character working at developing products specifically for left-handed people. This idea was later cut, but it provides an incomparable insight into where Lee's sympathies lie. The left-handed are still, in a lingering prejudice, routinely forced to use their right hands in much of Taiwan, and indeed in much of Asia. A sympathy with, and concern for, the metaphorically left-handed in many spheres of life could be said to characterize all the films of Lee.

There is a mass of incidental detail included - how President Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) visited Lee at his parental home near Tainan, how the original author of Brokeback Mountain, Annie Proulx, initially doubted if Lee was the right director for it, how The Wedding Banquet was shot in six weeks for US$750,000 but made US$32 million, proportionately surpassing even Jurassic Park, and of how Lee appears himself in that movie, speaking the single but crucial line about the over-the-top wedding-day antics, "You're witnessing the result of 5,000 years of sexual repression."

Lee has said of himself "I don't have a hobby. I don't have a life," and "I would like to live inside the film and observe the world from the other side of the screen" (providing this book with its subtitle). But there's something more to this than meets the eye. It's the attitude, usually unspoken, of many of the very greatest artists. Their creations are everything, and there's no time - certainly no imaginative time - for anything much else. Shakespeare seems to have done little and traveled nowhere, while Mozart was so involved with music that his daily life reads like a sad, then a tragic, joke.

It's a big claim to make for Taiwan's most famous son, and it's not made in this book. But the point is that Lee is of that same, rare personality type, ambitious only for his work, and endlessly inhabiting a world alongside his characters - he lives, not in glamorous Hollywood, but in an unassuming New York suburb. And it's an understanding of the deep nature of her subject that makes Dilley's groundbreaking and comprehensive book such a rewarding read, and such a very fine achievement.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.