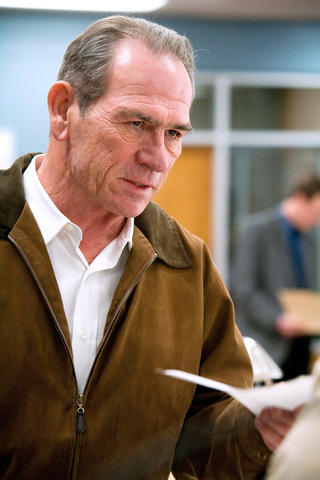

Viewed from one angle - straight on, from the ground level of its busy plot - In the Valley of Elah might be mistaken for a tidy crime procedural. A retired military police officer named Hank Deerfield (played by Tommy Lee Jones with his usual brisk, gruff economy) learns that his son Mike (Jonathan Tucker), an Army specialist recently returned from Iraq, has gone AWOL from his base in New Mexico.

Before long, the young man's charred and dismembered remains are found in the desert, and Hank joins Emily Sanders, a local detective played by Charlize Theron, in trying to figure out who could have done such a terrible thing to his boy.

As in an episode of Law & Order, suspicion veers one way and then another as new information comes to light. Paul Haggis, the writer and director, obeys the rules of the whodunit genre by providing answers to some of the basic, questions at the center of the film.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF LONG SHONG

But an air of irresolution nonetheless lingers around it, a sorrowful, frustrated sense that the deepest mysteries cannot be contained within any narrative framework. Underneath its deceptively quiet surface is a raw, angry, earnest attempt to grasp the moral consequences of the war in Iraq, and to stare without blinking into the chasm that divides those who are fighting it from their families, their fellow citizens and one another.

This is not to say that the detective story, suggested by the actual murder of Specialist Richard Davis in 2003, is entirely beside the point. Rather, the mechanics of the plot - the forensic discoveries, the squabbles over jurisdiction between military and civilian authority, the rounds of paperwork and the squad-room arguments - serve as the scaffolding for a more unsettling, open-ended inquiry. As much as Hank wants to know what happened to Mike the night he died, his real quest is to find out who his son was, and what happened to him in Iraq.

The only clues he has are some JPEGs his son e-mailed him, the memory of a desperate late-night phone call from the war zone and some smeary, scrambled video recovered from Mike's cell phone. These hectic, unfocused clips stand in jarring, pointed contrast to the neatly composed frames and carefully paced shots that make up most of Haggis' film, and they pose an agonizing challenge: How do you extract meaning from such chaos?

To his great credit, Haggis tries to coax an answer out of his story rather than imposing one on it from the start, as he did in Crash. That film, which owes its best picture Oscar to the dedication of its cast and the obviousness of its themes, turned racial intolerance into fodder for a self-righteous, schematic allegory.

While In the Valley of Elah has its share of overreaching and throat clearing - including clumsy references to the biblical story of David and Goliath, the source of its title - it is mostly free of moral grandstanding. (A brief scene in which Hank gives voice to some of his half-buried ethnic bigotry is more credible than any of the similar moments that make up most of Crash.)

Not that the message of In the Valley of Elah is ambiguous or unclear. The message is that the war in Iraq has damaged this country in ways we have only begun to grasp. For some people this will seem like old news. Others - in particular those who pretend that railing against movies they haven't seen is a form of rational political discourse - may persuade themselves that it is provocative or controversial.

But however you judge the movie's politics, and whatever its flaws, there is something inarguable, something irreducibly honest and right, about Jones' performance. Hank exists on a continuum with the other lawmen he has recently played, in particular the Texas sheriffs in The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, which he directed, and Joel and Ethan Coen's No Country for Old Men, which will be released later this fall.

Like them, Hank carries around an innate sense of right and wrong, and Jones's creased face, at once kindly and severe, is a manifest sign of his old-school temperament. Hank is the kind of man who shines his shoes every night, says grace before each meal and makes his motel-room bed according to military standards.

At every point, as Hank nags and pushes Emily in her investigation, the movie registers the panic and dread that he fights to keep down. These feelings come through to some extent in the reactions of his wife, Joan (Susan Sarandon), whom he tries to protect, but more decisively, and more hauntingly, through the moods Haggis creates (with the crucial assistance of Roger Deakins, the cinematographer responsible for the movie's austere, washed-out look, and Mark Isham, who wrote the eerie, sparingly applied musical score).

Almost no violence takes place on screen, but there are times when In the Valley of Elah feels almost like a horror film. Its steady crescendo of suspense builds toward the revelation - and vanquishing - of some unspeakable, monstrous evil.

But since the monster has no identifiable physical shape, it is not so easily defeated. While there are killers, liars and sadists to be found in this movie, there are not really any villains. And there is no reassuring conclusion. If it is anguished, even despairing, In the Valley of Elah is also compassionate. At heart it is a somber ballad about young men who remain lost in a dangerous, confusing place even after they come home.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the

Six weeks before I embarked on a research mission in Kyoto, I was sitting alone at a bar counter in Melbourne. Next to me, a woman was bragging loudly to a friend: She, too, was heading to Kyoto, I quickly discerned. Except her trip was in four months. And she’d just pulled an all-nighter booking restaurant reservations. As I snooped on the conversation, I broke out in a sweat, panicking because I’d yet to secure a single table. Then I remembered: Eating well in Japan is absolutely not something to lose sleep over. It’s true that the best-known institutions book up faster

Though the total area of Penghu isn’t that large, exploring all of it — including its numerous outlying islands — could easily take a couple of weeks. The most remote township accessible by road from Magong City (馬公市) is Siyu (西嶼鄉), and this place alone deserves at least two days to fully appreciate. Whether it’s beaches, architecture, museums, snacks, sunrises or sunsets that attract you, Siyu has something for everyone. Though only 5km from Magong by sea, no ferry service currently exists and it must be reached by a long circuitous route around the main island of Penghu, with the