After the literary critic Anatole Broyard died in 1990, his family arranged a memorial reception at a suburban Connecticut yacht club. It was a club that claimed to have no black members until, after Broyard's death, his mixed racial lineage was made known. After that, the club cited him as evidence of integration.

What was it like for Broyard to keep his secret in such surroundings? For a self-made man who had come so far in life, reading so many books in the process, did the clubhouse's view of Long Island Sound bring to mind the grand illusions of "The Great Gatsby?"

Not likely, says his smart, tough-minded daughter, Bliss Broyard, in One Drop, an investigative memoir about her father's life. As this fascinating, insightful book makes clear, Broyard left a legacy of racial confusion and great autobiographical material, not necessarily in that order.

Broyard shares her father's bracingly unsentimental spirit, to the point where she knows that he had none of Jay Gatsby's self-congratulatory outlook or sense of American tragedy. More to the point, she says, "It never seemed to occur to him that someone might want to keep him out."

When a guest at the memorial service noticed three light-skinned black people sitting with the Broyards, he was surprised that the family had so much help. But those weren't the servants; they were black Broyards who had been kept at arm's length by Anatole, whose birth certificate listed him as white. By the time he got to Connecticut, after early years in New Orleans, a Brooklyn boyhood and time spent in the army and Greenwich Village, he no longer talked about his lineage. Black friends assumed he was black. White people didn't ask what they thought of as rude questions. It was a rare moment in the Broyard household - say, when dinner guests realized that Bliss and her brother, Todd, knew nothing about their black heritage - when race seemed to make any difference at all.

Only after her father died did Broyard begin to realize how little she understood. And so she began, in ways that elevate One Drop far above the usual family-revisionist memoir, to make up for lost time. She knew no Broyards in New York, but found plenty in Los Angeles, even bringing them together for a family reunion as an early step in her process of discovery. What made this gathering tricky is that some Broyards regarded themselves as white and others as black, drawing vehemently different conclusions from similar sets of facts.

Broyard knew that her father's heritage was an open secret when she found a close confidant in Henry Louis Gates Jr, the renowned scholar. She got to know Gates by his nickname, Skip; she marveled at how generous he was with his time and interest. Then she learned that he planned to write the Broyard story for The New Yorker, and she was infuriated at having been so manipulatively treated. "Years later," she writes astutely, "I'd realize that my biggest fear was that Gates, a stranger who had never even met my father, would understand him better than I could." But she sharply excoriates Gates for his tactics, his glibness and the harm that she feels his article inflicted on her family.

When she published her first book, a story collection called My Father, Dancing in 2000, Broyard had not written about race. Yet her book was included in the African-American Book Expo in Chicago and on the Black History Month agenda. An investigation into her own past and her family's was clearly something she could not avoid.

A half-hidden family history is no guarantee of an interesting one, however. And for all its prodigious research, One Drop deals more engrossingly with the stories of Broyard and her closest relatives than it does with the 18th-century origins of the Broyards in the US.

Nonetheless, armed with the knowledge that genealogical Web sites are almost as popular as pornographic ones, Broyard zealously assembled an account of her roots. Among the first things she discovers about a large, Creole, New Orleans-based family like hers is that racial delineations and stereotypes make no sense at all.

And slavery, which she regards as a defining issue in matters of black identity, holds its own share of surprises. "In a few short hours, I'd gone from believing that my great-grandmother was born a slave to discovering that she'd grown up in a family of black slave owners," she writes after one fact-finding trip. "These weren't the noble tragic figures I'd been expecting to encounter."

Though its scope is large, the heart of One Drop lies with the author's father. She must try - as Philip Roth did in The Human Stain, a book that was seemingly prompted by the Broyard story but goes unmentioned here - to understand the choices he made, whether by action or omission. In a speculative account of what happened when her father applied for a Social Security card, Broyard guesses at how he might have been flummoxed by the decision of what racial identity to choose yet unaware of how important this choice would be. "I doubt that my father walked away feeling that he'd redirected the course of his life," she writes.

Drawing on both her father's autobiographical account and some of what Gates had to say, One Drop culminates in a cultural and intellectual history of Broyard's life and times. His Greenwich Village days (described in his book Kafka Was the Rage) were full of ambition and contention, not to mention consummate lady-killing. (Broyard was "New Orleans French, handsome, sensual, ironic," according to the hot-blooded diarist Anais Nin.) And some of his most assertive early essays about race and hip-ness made his bona fides clear.

Broyard proudly kept a 1950 issue of Commentary near the family's dinner table. But the author's identifying note had been neatly cut out of the contributor's page. Now his daughter knows what it said: that Anatole Broyard was "an anatomist of the Negro personality in a white world." And she wonders, with lucid and sharp introspection, how her own life would have changed if she had known that sooner.

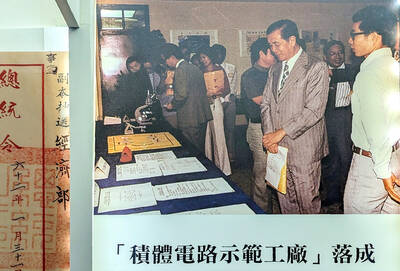

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,