Has it ever seemed clearer that fashion is not about clothes? Has it ever appeared more inevitable that the cult of the designer is slated for the cultural slag heap, there to join all those other monuments to the outmoded notion of the grand career (retrospective albums, DVD collections, the Great Novel)?

Fashion, like an awful lot of other stuff in the culture, is cracking apart before one's eyes. You're doomed if you try to see the field as some powerful system run by chic sadists ("Bore someone else with your questions," said Meryl Streep's Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada, snapping at her simpering minion in the weary tone of a burned-out dominatrix).

Fashion doesn't come just from the runway anymore, if it ever really did. And it doesn't come from Project Runway either. Rather, it seems to happen spontaneously and then spread like some mostly benign contagion, a germ carried in the air and contracted in this store, that magazine, this corner of the city and in ways that fashion bibles rarely bother to note.

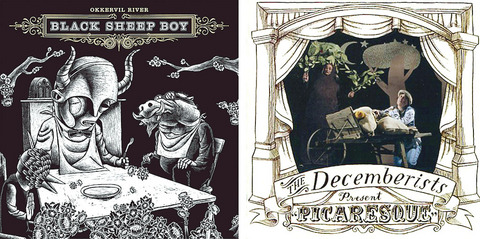

Trends emerge, apparently from nowhere: They are fashion. This process can be intoxicating to watch. Suddenly young people in rock bands like the Decemberists and My Morning Jacket begin dressing as if playing a rock club was no different from running copies behind a counter at Kinko's. In place of stage costumes, they favor cheap sweater vests and no-brand thrift shop jeans. They make such a success of looking frumpy that their frumpiness develops into a style despite itself.

How can one tell? Well, already last season in Paris, Sarah Lerfel, a farsighted owner of the celebrated boutique Colette, was talking about a trend that sounded a lot like the Return of Grunge.

Fashion in that sense is a Mobius strip, a flexible circuit, both variable and closed. Designers shine one season on the face side of the loop, the arc turns and suddenly you can't see them anymore. A year ago the name of Roland Mouret was on everyone's lips. The hobbled skirts and elevator stilettos he promoted in the fall of 2005 were greeted by some as precisely the antidote to a sartorial landscape grown neutral and drab.

It was meant to happen in a big way for Mouret. The fix was in at Vogue. And then well nothing. A couple of movie people were spotted wobbling down that purgatorial road to nowhere, the red carpet, in his creations. Yet the predicted breakout did not take place; the gyre turned and Mouret faded away. Until late this November, when, with hardly any fanfare, there he was again, proudly adorning the racks at the Gap. The Gap?

"I was interested in the opportunity to make my designs available to a broader audience," the designer said, after a small capsule collection of his was shipped to select local Gap stores.

Was Mouret selling out? He was not. He was just doing what every designer from Stella McCartney to Karl Lagerfeld to Vera Wang has recently done, buying his ticket to board the mass-market gravy train. As it happens, this is a fine thing that has happened to fashion, since the democratization of design is a value that has been trumpeted by every theoretician of the applied arts since the Bauhaus.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

It is thrilling somehow to see visual ideas first created to be pitched to the rarefied tastes of a group of mandarins leak out to the broader population. It is a pleasure to realize that our tastes, after all, are not formed at the whim of some underfed dictators of editorial chic. And there is a lot of fun to be had in tracking the serendipitous way that cultures, both high and low, unexpectedly collide.

Think of how hipsters have suddenly started looking like Paul Bunyan. Think about how the grizzled, bearded look now affected by half of the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn this winter was only a short time ago derided as an affectation of gay bears, a small minority of hyper-masculine men who affect potbellies, clodhoppers and lavish chin whiskers.

We are talking full shrubs here, not mangy soul patches, the kind of beards that gay bears once seemed to be the only ones to flaunt (the better to attract each other at bars and roundups like the annual Bearapalooza or the Furball in Canada).

Is it because atavism runs deep in fashion that the style abruptly leaped across the population boundaries and has now made a startling appearance among the ranks of cool young men, mostly straight?

In the late summer of last year, one spotted a scant few beards around town; then, come autumn, whole blocks of Manhattan's Lower East Side were crawling with guys who looked like the musician Devendra Banhart, who in turn seemed to have copped his look from Peter Orlovsky, the poet lover for three decades of Allen Ginsberg, the late literary genius who, after his first visit to India, affected a beard woolier than anything you'd see on a mud daubed sadhu.

By this past holiday season, whether at clubs and bars like Supreme Trading or Black Betty in Brooklyn, the bearded hipster-mullah-hippie look had proliferated to the point where one could barely distinguish musicians from the local Hasidim. (In the case of the popular rapper Matisyahu, an Orthodox Jew, the distinction was moot.)

Shifts of taste and style are trivialities, of course, without any serious meaning. But they do perform one important function, as Proust pointed out: They notch our hours and moments and decades and leave us with visual mnemonics, clues by which to remember where and in which dress and what jeans (and wearing what cologne) one was at a particular time. Tracking the way styles evolve gives us insight, too, into the forms of beauty we choose to idealize.

Models who were vacant optimistic cheerleader types prevailed in the politically clueless 1970s (Christie Brinkley, Patti Hansen, Shelley Hack); brooding brunettes took over during the Age of Reagan (Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford and Yasmeen Ghauri); and off-kilter aristocratic types (Guinevere van Seenus, Stella Tennant, Erin O'Connor), emblematic of upper class women, came to the fore during the second Bush imperium.

What fashion now prefers as a beauty ideal is another type, the robot, personified by the stunning Raquel Zimmerman, a blond Brazilian of German heritage whose physical proportions are so symmetrical that many designers use her body as a template. That Zimmerman also has a kind of vacant cyborg aspect cannot be altogether incidental. Possibly this is the reason why Louis Vuitton hired her for a new ad campaign in which her face has been made up and manipulated so aggressively as to render her less humanly expressive than Lara Croft.

Was this intentional? Who knows? But it is no stretch to extrapolate from Zimmerman's popularity to a time when live models will be dispensed with altogether, in favor of creatures written in CGI. That is not to suggest there is a master plan. There rarely is. Or is there?

The guessing game keeps fashion fun for observers, that and its magpie habit of plucking from the cultural grab bag anything bright or unexpected with which to keep us amused.

I am thinking of a micro-fad recently noted among privileged young women in elite neighborhoods of Manhattan's Upper East Side, the wearing of bedroom slippers on the streets. "It started at boarding schools two years ago, when every single boarding-school kid was wearing them," Signe Conway, a senior at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, explained last week, as she stood outside Yura & Co, a coffee shop that doubles as a private neighborhood clubhouse.

Conway, 17, was wearing a pair of fuzzy suede moccasin-style slippers, the sort lined with shearling and with a roll of fur turned down on each side. The slippers are sold by L.L. Bean; they caught on when girls' school administrators banned the wearing of the now ubiquitous Ugg boots.

Like flip-flops in January, slippers on the sidewalk flout logic. They blur lines. They catch the eye and jolt one into the subtle realization that boundaries between public space and private are permeable. The gesture is small but it reminds one that fashion is a monumental system built on coded details.

If one suddenly decides to colonize the sidewalks and treat them as though one were home in the bedroom, it is fashion that issues the license to proceed.

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers