How depressing, how utterly unjust, to be the one in your social circle who is aging least gracefully.

In a laboratory at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, Matthias is learning about time's caprice the hard way. At 28, getting on for a rhesus monkey, Matthias is losing his hair, lugging a paunch and getting a face full of wrinkles.

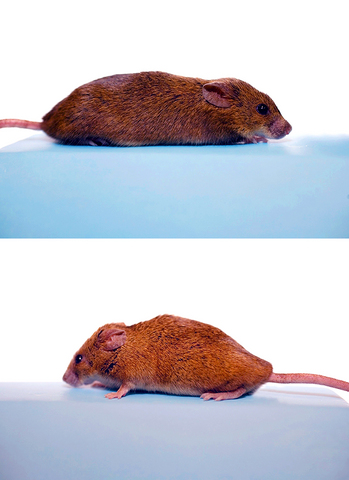

Yet in the cage next to his, gleefully hooting at strangers, one of Matthias' lab mates, Rudy, is the picture of monkey vitality, although he is slightly older. Thin and feisty, Rudy stops grooming his smooth coat just long enough to pirouette toward a proffered piece of fruit.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Tempted with the same treat, Matthias rises wearily and extends a frail hand. "You can really see the difference," said Ricki Colman, an associate scientist at the center who cares for the animals.

What a visitor cannot see may be even more interesting. As a result of a simple lifestyle intervention, Rudy and primates like him seem poised to live very long, very vital lives.

This approach, called calorie restriction, involves eating about 30 percent fewer calories than normal while still getting adequate amounts of vitamins, minerals and other nutrients. Aside from direct genetic manipulation, calorie restriction is the only strategy known to extend life consistently in a variety of animal species.

How this drastic diet affects the body has been the subject of intense research. Recently, the effort has begun to bear fruit, producing a steady stream of studies indicating that the rate of aging is plastic, not fixed, and that it can be manipulated.

In the last year, calorie-restricted diets have been shown in various animals to affect molecular pathways likely to be involved in the progression of Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, heart disease, Parkinson's disease and cancer. Earlier this year, researchers studying dietary effects on humans went so far as to claim that calorie restriction may be more effective than exercise at preventing age-related diseases.

Monkeys like Rudy seem to be proving the thesis.

The findings cast doubt on long-held scientific and cultural beliefs regarding the inevitability of the body's decline.

"Calorie restriction has the potential to help us identify anti-aging mechanisms throughout the body," said Richard Weindruch, a gerontologist at the University of Wisconsin who directs research on the monkeys.

Aging is a complicated phenomenon, the intersection of an array of biological processes set in motion by genetics, lifestyle, even evolution itself.

Still, in laboratories around the world, scientists are becoming adept at breeding animal Methuselahs, extraordinarily long lived and healthy worms, fish, mice and flies.

In 1935, Clive McCay, a nutritionist at Cornell University, discovered that mice that were fed 30 percent fewer calories lived about 40 percent longer than their free-grazing laboratory mates. The dieting mice were also more physically active and far less prone to the diseases of advanced age.

McCay's experiment has been successfully duplicated in a variety of species. In almost every instance, the subjects on low-calorie diets have proven to be not just longer lived, but also more resistant to age-related ailments.

"In mice, calorie restriction doesn't just extend life span," said Leonard Guarente, professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "It mitigates many diseases of aging: cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease. The gain is just enormous."

For years, scientists financed by the National Institute on Aging have closely monitored rhesus monkeys on restricted and normal-calorie diets. At the University of Wisconsin, where 50 animals survive from the original group of 76, the differences are just now becoming apparent in the older animals.

Those on normal diets, like Matthias, are beginning to show signs of advancing age similar to those seen in humans. Three of them, for instance, have developed diabetes, and a fourth has died of the disease. Five have died of cancer.

But Rudy and his colleagues on low-calorie meal plans are faring better. None have diabetes, and only three have died of cancer. It is too early to know if they will outlive their lab mates, but the dieters here and at the other labs also have lower blood pressure and lower blood levels of certain dangerous fats, glucose and insulin.

"The preliminary indicators are that we're looking at a robust life extension in the restricted animals," Weindruch said.

Mike Linksvayer, a 36-year-old chief technology officer at a San Francisco nonprofit group, embarked on a calorie-restricted diet six years ago. On an average day, he eats an apple or some cereal for breakfast, followed by a small vegan dish at lunch. Dinner is whatever his wife has cooked, excluding bread, rice, sugar and whatever else Linksvayer deems unhealthy (this often includes the entree). On weekends, he occasionally fasts.

Linksvayer, 182cm and 61kg, estimated that he gets by on about 2,000 to 2,100 calories a day, a low number for men of his age and activity level, and his blood pressure is a remarkably low 112 over 63. He said he has never been in better health.

"I don't really get sick," he said. "Mostly I do the diet to be healthier, but if it helps me live longer, hey, I'll take that, too."

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have been tracking the health of small groups of calorie-restricted dieters. Earlier this year, they reported that the dieters had better-functioning hearts and fewer signs of inflammation, which is a precursor to clogged arteries, than similar subjects on regular diets.

In previous studies, people in calorie-restricted groups were shown to have lower levels of LDL, the so-called bad cholesterol, and triglycerides. They also showed higher levels of HDL, the so-called good cholesterol, virtually no arterial blockage and, like Linksvayer, remarkably low blood pressure.

These studies and others have led many scientists to believe they have stumbled onto a central determinant of natural life span. Animals on restricted diets seem particularly resistant to environmental stresses like oxidation and heat, perhaps even radiation. "It is a very deep, very important function," Miller said. Experts theorize that limited access to energy alarms the body, so to speak, activating a cascade of biochemical signals that tell each cell to direct energy away from reproductive functions, toward repair and maintenance. The calorie-restricted organism is stronger, according to this hypothesis, because individual cells are more efficiently repairing mutations, using energy, defending themselves and mopping up harmful by-products like free radicals.

Some ethicists believe that the all-out determination to extend life span is veined with arrogance. As appointments with death are postponed, says Leon Kass, former chairman of the President's Council on Bioethics, human lives may become less engaging, less meaningful, even less beautiful.

"Mortality makes life matter," Kass recently wrote. "Immortality is a kind of oblivion — like death itself."

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was