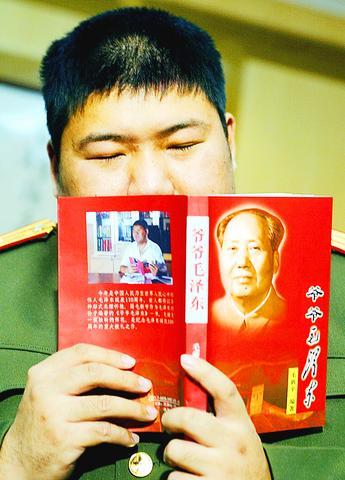

Mao Xinyu (

"In this new century, this new period of history, to publicize Mao Zedong's (

PHOTO: REUTERS

More than a quarter-century after his death in 1976, Mao's continuing status as a global pop icon contrasts with the increasingly acknowledged bankruptcy of his politics, a pretext for all kinds of irony.

The burden of reconciling China's past and present has been thrust on the distended frame of his grandson, who is said to have grown up sheltered by servants and guards, kidding classmates about what he'd do when he took power.

In a generation of "little emperors," he appeared to fit the mould better than any, logging mediocre test scores and tipping the scales at more than 114kg.

Today, as an army-trained Mao historian and lieutenant-colonel, Xinyu, 33, remains a ceremonial figure. But while he has slimmed little, he has matured a good deal.

Sitting back in a voluminous green uniform, swearing to uphold Mao's guerrilla gospel, he faintly resembles his grandfather -- part country bumpkin, part quixotic bookworm, part sprawled-out sovereign.

"Aya, there's pressure, there's pressure," he sighed, with a puffy-cheeked grin, at the end of an interview. "Because the whole nation's people have their eyes on me."

Moments after Xinyu left, one of his publicity aides at the Academy of Military Sciences explained that "pressure" was meant to convey filial respect, all the more so for an ancestor of his grandfather's stature.

Mao's 110th birthday, Dec. 26, came and went last month, making no great waves in Chinese public life.

The Communist Party aired the usual television hagiographies while capitalistic co-sponsors peddled the latest gimmicks, from books spinning Mao's wartime survival tactics into management tips to hip-hop music recordings of his trademark theories.

Xinyu, for his part, did a rare run of interviews and book signings to promote his new anecdotal history, Grandpa Mao Zedong.

The paperback has sold several tens of thousands of copies, the Ph.D. replied modestly when asked. Later he suggested, "I'll give you the rights. You can translate it!"

The Great Helmsman named him Xinyu, or "new universe."

His father, Mao Anqing, the chairman's second son, was a party interpreter before succumbing to schizophrenia; his mother Shao Hua, an esteemed photojournalist, is a major-general. His wife is also in the army.

In China's elite circles today, many so-called princelings milk their pedigree to find jobs in prize industries, from real estate (party boss Hu Jintao's (胡錦濤) daughter) to semi-conductors (military chief Jiang Zemin's (江澤民) son). Some hold official posts themselves.

For Mao's heirs, the chambers of party power were seemingly off limits, the boardrooms of business sure to incur scandal.

So the family -- said to suffer from bad genes and be subject to bad grudges by elites rehabilitated after the Chairman's 1966 to 1976 Cultural Revolution -- came to depend on the military.

Xinyu insists his clan simply have their own special calling, to act as "successors" to Mao's revolutionary work.

"As the Chairman's relatives, we must take heed to serve the people at every turn," he said.

As for those counter-revolutionaries who exploit Mao's image for personal gain, with kitsch cigarette lighters and so on, he has a rosy-red outlook. "If you ask to me look at these phenomena and what they relate to, I believe China's common people want to have beliefs and spiritual sustenance."

"Since the 100th anniversary especially, I feel that common Chinese people's spiritual beliefs and spiritual sustenance have been embodied in Chairman Mao."

That was less than apparent in the capital on Mao's 110th birthday. While many stopped to snap souvenir photos before the Tiananmen rostrum, where Mao proclaimed the People's Republic in 1949 and where his portrait still keeps watch, perhaps as many lined up outside department stores for shots with Santa Claus.

Xinyu said that one reason he wrote his book was to dispel certain Mao "myths," although he declined to cite examples.

The authorities have banned some books over the years, such as physician Li Zhisui's notorious portrayal of Mao as a randy megalomaniac.

As with many Chinese biographies of the late Chairman, 90 percent of Xinyu's volume focuses on the pre-1949 Mao, credited with emancipating the masses after millennia of feudalism. The Mao blamed for 30 to 50 million deaths from famine during the Great Leap Forward and millions more in the Cultural Revolution goes unmentioned.

But even this self-styled Mao disciple bows to the accepted verdict in China: Mao made mistakes, but his contributions exceeded them.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only