Twenty-two hundred years ago, the great Greek mathematician Archimedes wrote a treatise called the Stomachion, or stomach. Unlike his other writings, it soon fell into obscurity. Little of it survived, and no one knew what to make of it.

But now a historian of mathematics at Stanford, sifting through ancient parchment overwritten by monks and nearly ruined by mold, appears to have solved the mystery of what the treatise was about. In the process, he has opened a surprising new window on the work of the genius best remembered (perhaps apocryphally) for his cry of "Eureka!" when he discovered a clever way to determine whether a king's crown was pure gold.

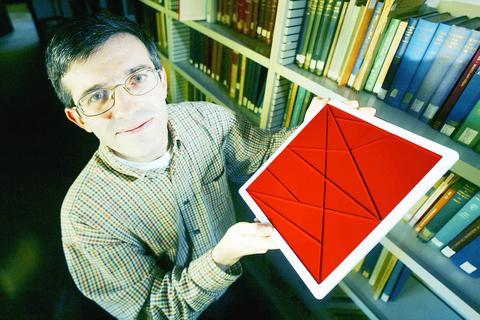

PHOTO: NY TIMES

The Stomachion, concludes the historian, Reviel Netz, was far ahead of its time: a treatise on combinatorics, a field that did not come into its own until the rise of computer science.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

The goal of combinatorics is to determine how many ways a given problem can be solved. And finding the number of ways that the problem posed in the Stomachion (pronounced sto-MOCK-yon) can be solved is so difficult that when Netz asked a team of four combinatorics experts to do it, it took them six weeks.

While Netz acknowledges that his findings cannot be proved with absolute certainty, he has presented the work to other scholars, and they say they agree with his interpretation.

On a recent snowy Sunday morning at Princeton University, three dozen academics gathered to hear Netz speak, and then congratulated him, saying his arguments made sense. "I'm convinced," said Stephen Menn, a McGill University historian of ancient mathematics, in an interview at the end of the two-hour session.

Among all of Archimedes' works, the Stomachion has attracted the least attention, ignored or dismissed as unimportant or unintelligible. Only a tiny fragment of the introduction survived, and as far as anyone could tell, it seemed to be about an ancient children's puzzle -- also known as the Stomachion -- that involved putting strips of paper together in different ways to make different shapes. It made no sense for a man of Archimedes' stature to care about such a game. As a result, Netz said, "people said, `We don't know what it is about.'"

In fact, he has concluded, the prevailing wisdom was based on a misinterpretation. Archimedes was not trying to piece together strips of paper into different shapes; he was trying to see how many ways the 14 irregular strips could be put together to make a square.

The answer -- 17,152 -- required a careful and systematic counting of all possibilities. "It was hard," said Persi Diaconis, a Stanford statistician who worked on it along with a colleague, Susan Holmes, who is also his wife, and a second husband-and-wife team of combinatorial mathematicians, Ronald Graham and Fan Chung from the University of California, San Diego.

Independently, a computer scientist, William H. Cutler at Chicago Rawhide, a manufacturer of oil seals in Elgin, Illinois, wrote a program that confirmed that the mathematicians' answer was correct.

Perhaps as remarkable as the discovery that Archimedes knew combinatorics is the story of a manuscript that dates to 975, written in Greek on parchment. It is one of three sets of copies of Archimedes' works that were available in the Middle Ages. (The others are lost, and neither contained the Stomachion.)

"For Archimedes, as for all others from antiquity, we don't have the original works," Netz said. "What we have are copies of copies of copies."

Investigators evaluate copies by asking whether they agree on the text they have in common, and by looking for unique passages, which lend them particular interest. By those measures, the manuscript was invaluable. But it was nearly lost.

In the 13th century, Netz explained, Christian monks, needing vellum for a prayer book, ripped the manuscript apart, washed it, folded its pages in half and covered it with religious text. After centuries of use, the prayer book -- known as a palimpsest, because it contains text that is written over -- ended up in a monastery in Constantinople.

Johan Ludvig Heiberg, a Danish scholar, found it in 1906, in the library of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Istanbul. He noticed faint tracings of mathematics under the prayers. Using a magnifying glass, he transcribed what he could and photographed about two-thirds of the pages. Then the document disappeared, lost along with other precious manuscripts in the strife between the Greeks and the Turks.

It reappeared in the 1970s, in the hands of a French family that had bought it in Istanbul in the early 1920s and held it for five decades before trying to sell it. They had trouble finding a buyer, however, in part because there was some question of whether they legally owned it. But also, the manuscript looked terrible. It had been ravaged by mold during the years the family kept it.

In 1998, an anonymous billionaire bought it for US$2 million and lent it to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where it still resides.

"I should emphasize how incredibly uncommon the situation is," Netz said.

With the manuscript in hand, a small group of scholars set out to reconstruct the original Greek text. It was not easy. "You look with the naked eye and you see nothing, absolutely nothing," Netz said.

Ultraviolet light revealed faint traces of writing, but it included both the prayers and the mathematics. "The major problem is the combination of the fact that many characters are hidden with the fact that many are so faint that they are invisible," Netz said. Then there are the gaps where the pages were ripped or eaten away by mold.

Computer imaging helped. Roger Easton of the Rochester Institute of Technology, Keith Knox of the Boeing Corp. and William Christens-Barry of Johns Hopkins University managed to write programs to pick out writing from the "noise" around it, and in many places the Greek letters fairly pop off the computer screen.

"The product of the software is incredible," Netz said. But it too has limitations, especially near the tattered edges of the pages. To reconstruct the writings, Netz and Nigel Wilson, a classics professor at Oxford University, are using every tool available: ultraviolet light, the computer images, Heiberg's photographs and their own intimate knowledge of ancient Greek texts. Still, in some areas, "the text is likely to remain conjecture," Netz said.

It was chance that led Netz to his first insight into the nature of the Stomachion. Last August, he says, just as he was about to start transcribing one of the manuscript pages, he got a gift in the mail, a blue cut-glass model of a Stomachion puzzle. It was made by a retired businessman from California who found Netz on the Internet as a renowned Archimedes scholar. Looking at the model, Netz realized that a diagram on the page he was transcribing was actually a rearrangement of the pieces of the Stomachion puzzle. Suddenly, he understood what Archimedes was getting at.

The diagram involved 14 pieces, and the word "multitude" seemed to be associated with it. Heiberg and those who followed him thought this meant that you could get many figures by rearranging the pieces.

"This is part of the reason people didn't see what it was about," Netz said. But the old interpretation seemed trivial, hardly worth Archimedes' time.

As he examined the manuscript pages, piecing together their text, he realized that what Archimedes was really asking seemed to be, "How many ways can you put the pieces together to make a square?" That question, Netz said, "has mathematical meaning."

"People assumed there wasn't any combinatorics in antiquity," he went on. "So it didn't trigger the observation when Archimedes says there are many arrangements and he will calculate them. But that's what Archimedes did; his introductions are always to the point."

But did Archimedes solve the problem? "I am sure he solved it or he would not have stated it," Netz said. "I do not know if he solved it correctly."

As for the name, derived from the Greek word for stomach, mathematicians are uncertain. But Diaconis has a hunch.

"It comes from `stomach turner,'" he said. "If you get involved with it, that's what happens."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the