Retired builder Ivan Plotnikov always regretted he wasn't born Richard the Lionheart.

At age 4, he promised himself and his parents that he, like England's warrior king, would have his own castle someday. At age 7, he drew out a plan. And at age 19, he robbed a bank in a failed effort to get the money to pay for its construction.

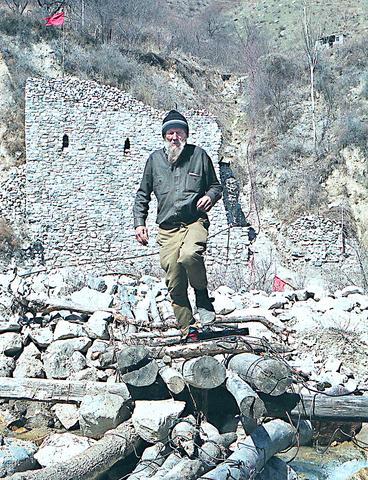

PHOTO: AP

Yet, 35 years later, a half-finished gray stone bastion stands amid rickety little weekend cottages on the bank of a mountain river in the picturesque Aksay Gorge outside Kazakhstan's biggest city, Almaty.

Fifteen meters tall and about 10m wide, it looks like a small medieval castle from afar. Only the freshly laid rocks at the top give away its true age.

"Are you tourists, journalists or theater lovers?" the heavily bearded Plotnikov calls out to visitors crossing a small footbridge spanning the river.

He's got a card certifying that he's an invalid, and another that proves his proud membership in the Communist Party. He got the latter only recently -- in Soviet times, when the party accepted only the cream of the crop, a convicted bank robber who did time in a psychiatric ward couldn't make the grade.

"I will keep building this fortress until I die, like Lenin and Stalin built communism," Plotnikov tells his visitors.

Small beginnings

He began building the castle in 1983, earning a living at construction sites during the week and spending weekends in the gorge. Since going on a disability pension five years ago, he has devoted most of his time to raising the bastion.

He must wait out the harsh winter at his two-room apartment in Almaty, where utility bills eat up 5,000 tenge (US$33) of his 5,900-tenge (US$39) monthly pension. But when the cold begins to ebb, he camps out at the castle, which is outfitted with a cot, a small heater and a fireplace. He draws water from the river and takes a weekly hike to the closest village, 5km away, to buy tea, bread and the few other staples he can afford.

"The apartment eats up all my money; there's nothing left for cement," Plotnikov laments. "So I hire myself out to cottage-owners, helping dig potatoes. Sometimes they give me money, but more often they give me food or cement."

Plotnikov wrestles rocks weighing up to 50kg up from the river for the walls. He figures that over the 20 years he's carried about 800 tonnes up the bank.

He doesn't know just how the idea of building a castle came to him. He only remembers that from early childhood, he would close his eyes and see a stone bastion with little windows, arches and a flag -- a red flag. He says family legend has it that his grandmother and grandfather were Russian nobles.

"I was born in China in 1949," Plotnikov says. "My mother told me that she and her parents fled Russia on the eve of the revolution."

Childhood dreams

When Plotnikov was 4, his family returned to Russia. They lived for a time in the Siberian city of Omsk, then moved south to Almaty, in the then-Soviet republic of Kazakhstan.

"I was already getting on my parents' nerves with my knights, fortresses and chain-mail shirts," Plotnikov recalls.

In school, when he was 7, he got a top grade for a mock-up of a castle. In a later class, he drafted a construction plan. He still carries the yellowed drawing in his chest pocket.

"My parents refused to finance my project. That's when I decided to rob the savings bank," he says.

"On Aug. 13, 1963, I forced my way into an Almaty branch with a sawed-off shotgun. I pointed the gun at the cashier. She gave me five rubles. That's all she had, because the bank had just opened."

He was caught immediately. The investigators were unmoved by the story of his dream of building a castle. They took it as the ravings of a lunatic and he was sentenced to two years in a psychiatric hospital.

"Those were awful times. To this day I don't know what they cured me of. Maybe I really am sick," Plotnikov says.

He made his first stab at building a castle near Almaty, but there were too few rocks there and he had to drag them from far away. Then some friends showed him the site in the Aksay Gorge.

After two decades, he's built about half the bastion of his dreams. According to his plan, it should have two towers with a round arch in the middle.

"I won't have time to finish it before I die, but I hope someone will continue my work," Plotnikov says. "Maybe once it's finished, someone can open a restaurant here.

"There's a saying that a man should achieve three things before he dies: build a house, plant a tree and have a son. I don't have children, but I'm leaving a fortress. And maybe someone will remember Ivan."

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.