For 10-year-old schoolgirl Paola Muschette, the story of Panama's struggle for independence 100 years ago is straightforward.

"Our Panamanian patriots overthrew Colombian oppressors in November 1903, as US forces stood by to keep enemy troops from invading," she quotes from her history textbook. "Our patriots gave the US permission to build the Panama Canal."

But as Panama celebrates its centenary as a nation this year, many academics say that version of history is nothing but a legend and that the truth is less heroic.

PHOTO: REUTERS

As never before, local historians are challenging the official account of how Panama gained its independence, forcing Panamanians to question their national identity and raising the ire of the establishment.

"It's hard for people to accept, but Panama was created for profit," said Ovidio Diaz, a US-educated lawyer and author of How Wall Street Created a Nation. The book, published in 2001 in English, was recently translated into Spanish and is causing controversy in Panama and Colombia.

Money talks

According to Diaz, Panama was wooed away from Colombia by a Wall Street syndicate, led by financier J.P. Morgan that secretly paid US$3.5 million for the failed French canal construction concern in Panama, which went bankrupt in 1889.

With the acquiescence of US president Theodore Roosevelt, the syndicate bribed Panamanian politicians and Colombian generals into declaring the new state of Panama. This allowed the US to take over the French project and build its own canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans without interference, said Diaz.

"After the Panama uprising, the syndicate sold the US government the French canal shares for US$40 million," said Diaz, who spent years trawling through forgotten journalistic and congressional accounts of US efforts to build the Panama Canal in the early 1900s.

Colombia ruled what is today Panama after independence from Spain in 1821, but historians are often split over whether Panama's break with Bogota was the result of a genuine separatist movement or just due to US interference.

Some older Colombians still lament the loss of Panama 100 years ago. Relations between the two countries today are cordial but Panamanians see Colombia's drug trade and guerrilla war as a source of instability in the region.

Historians agree that Colombia, which had granted the rights to the failed French canal effort in the 1880s, made life difficult for the US in early 1903, asking huge sums of money in annual rent to build a canal on Colombian land.

Roosevelt, who was dedicated to forging a US-built canal in Panama, was frustrated by the lack of progress, saying he had a "mandate from civilization" to build the canal.

But from there on, history is open to interpretation.

According to Pulitzer prize-winning US historian David McCullough, Panamanians did revolt against Colombia on November 3 1903, with the only casualties being one man and a donkey on the Panamanian side.

On Nov. 6 at 12:51pm, only 70 minutes after the official cable reached the US announcing the Panama uprising, Washington recognized the Republic of Panama.

Panamanian historian Olmedo Beluche says Panama's independence was a sham because, "There's no evidence of any separatist movements in Panama," even after independence from Spain and Panama's inclusion into Greater Colombia in 1821.

In the zone

Under the Hay-Bunau Varilla treaty, the US won the rights to build an inter-oceanic canal, as well as consent to govern a 16km-wide area through the heart of Panama, known as the Canal Zone.

The zone, run from 1903 until it was dismantled in 1977, was operated under US federal laws. The US returned the canal to Panama on Dec. 31, 1999.

While the zone was under US control, Panamanians had no free access to the area, while black and white canal workers were segregated under a caste structure.

Juan David Morgan, a Panamanian intellectual who supports the view of a genuine independence struggle, says the canal zone was the price Panama had to pay for its freedom.

"Panama tried to cede from Colombia throughout the 19th century but could never defeat Colombian forces. US support was the only way to achieve emancipation," said Morgan.

The debate leaves ordinary Panamanians vexed, mostly preferring to believe the traditional view of their history.

But many agree Panama, home to 2.8 million people, needs to reconsider its identity this year.

"There are questions we need to answer," said 22-year-old student Enrique Lara. "Is Colombia our enemy or our ally? And, now the United States has handed back the canal and left, what opposing force is there to unite us?"

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

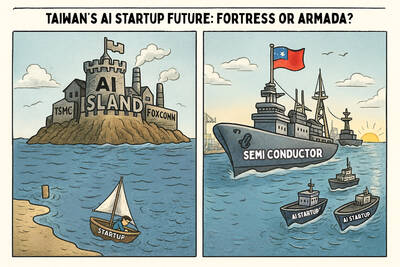

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders