Nowadays business deals have architects. Government policies have architects. There are even architects of sports victories. But architecture hasn't always permeated social consciousness, nor language.

An exhibition that opened yesterday at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), Archigram: Experimental Architecture 1961-1974, looks back to a major British movement that opened up architecture in these new ways and also helped define a 1960s futuristic aesthetic applied by others to Bond villains' headquarters, Monty Python's psychedelic animation and the Beatles' Yellow Submarine.

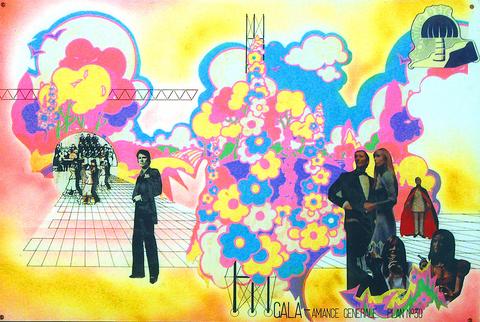

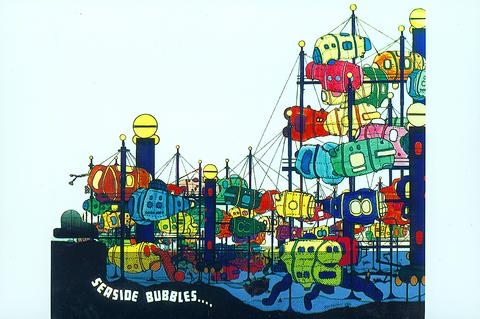

Archigram was founded as a magazine in 1961 by six London architects and then went on to spawn a movement. The magazine's pages were filled with manifestos, collaged space comics and fantastical drawings of an untold number of architectural projects, not one of which was ever built. It was a mod revolution that wanted to subvert stodgy urban landscapes with "gasket homes," "seaside bubbles," "underwater cities" and even an oil platform to be placed above Trafalgar Square.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TFAM

"We were designing non-houses, non-cities, non-building, non-places," said Peter Cook, one of Archigram's four surviving members and one of three in Taipei for the show's opening.

The designs were "anti-projects," and by the late 1960s they were part of the aesthetic and ideology of the "anti-establishment" movement. As architecture, the designs were, by and large, so imaginative that they were unbuildable. But they were imbued with a desire to dissolve cities, their existing hierarchies and their concrete exoskeletons. The term "archigram" was created by combining "architecture" with "telegram" and implied mobility, the lack of which they saw as an urban flaw to be rectified. So they invented "walking cities" that had legs and could move, "plug-in cities" that were interchangeable and "expendable place pads" as temporary, ad hoc homes. Drawings often called on materials that were inflatable, collapsible and not there when not needed. It was a vision of a society in flux.

In TFAM's galleries, these ideas are displayed in the form of more than 300 drawings, 14 architectural models and two extensive installations. Cook called it the second largest exhibition they've ever held in more than a decade of touring with their collection. One installation recreates a never-built 1969 design that fills a gallery with a Teletubby-like setting of astroturf, plastic flowers and inflatable dome homes. The second is a barrage of projected images, including a dozen slide projectors, video projectors and four television monitors.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TFAM

Much as American pop art is credited with bridging the gap between art and media, Archigram is credited with recognizing the confluence of architecture and advertising. (Imagine, for example, New York's Times Square or the Taipei Main Station MRT complex without ads ? it's virtually impossible because the ads are so central to what they are.)

Archigram member Michael Webb, also in Taipei for the opening, said that one of the things they realized was that "the labelling no longer applies," because in a dynamic environment, spaces can be used for anything. Advertisers discovered this long ago. As an example, Webb brought up the example of a New York commuter, a lawyer, who in a New York Times article claimed to actually enjoy the hours of traffic jams on his weekend commute because by employing a cell phone and a laptop computer sitting next to him in the passenger seat, it was the only time he could work without interruption.

"So you have this fellow doing all his work in an SUV, and still they build these office buildings everywhere. It doesn't work anymore, and it's still happening," said Webb.

"That's why we think the spirit of Archigram is still very much alive."

Archigram is on display through June 8 at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (台北市立美術館) located at 181, Sec. 3, Chungshan N. Rd. (北市中山北路三段181號). Hours are 9:30am to 5:30pm Tuesday to Sunday.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) controlled Executive Yuan (often called the Cabinet) finally fired back at the opposition-controlled Legislative Yuan in their ongoing struggle for control. The opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) acted surprised and outraged, but they should have seen it coming. Taiwan is now in a full-blown constitutional crisis. There are still peaceful ways out of this conflict, but with the KMT and TPP leadership in the hands of hardliners and the DPP having lost all patience, there is an alarming chance things could spiral out of control, threatening Taiwan’s democracy. This is no