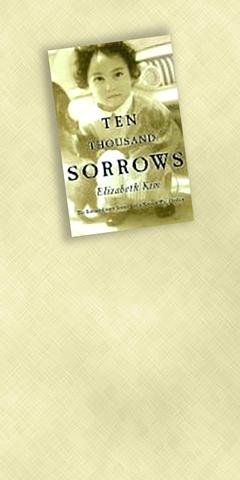

It's comparatively easy to find books detailing the abuse women are subjected to in Asian countries. This lively and readable book, however, goes one step further and tells a story that illustrates abuse so grotesque in both Asia and America that it would be difficult to decide which is the more terrible.

Elizabeth Kim was born in the 1950s to a Korean mother and a GI father. Her troubles began immediately. Because of the circumstances of her birth, no one in their village would accept her, and she and her mother were ostracized and made to live in a little hut apart from the others.

Life was nevertheless happy enough, with simple meals of kimchi and rice, and posies of wild flowers laid before the Buddha. But then a gang of male relatives arrived and demanded the child be sent to an orphanage. When the mother refused, she was tied up and hung from a beam in front of her daughter's eyes.

Following this "honor killing," the child was sent to an orphanage anyway. Run by strict Christian fundamentalists, this was more like a prison than a home. Children were stacked in crate-like cots and numbered. One night Elizabeth had to share her cot with a small boy. When she woke in the morning she found he had died from the cold.

Eventually she was adopted and flown to Los Angeles. From here she was driven out into the desert by her adoptive parents. It turned out to be the first of her journeys from the frying pan into the fire.

The couple were a Calvinist pastor of the most unrelenting kind and his equally intransigent spouse. Repression of pleasure in the world, and especially in the body, was everything. The walls were hung with pictures such as Holman Hunt's The Light of the World and Durer's praying hands.

All infringements of household rules were instantly punished, usually by beating with a wooden bat. These particular punishments, the lectures that preceded them and the screams they provoked, were recorded on a giant reel-to-reel tape recorder that stood in the living-room. When the pastor went to turn on the reel-to-reel, Elizabeth knew what to expect.

Finding refuge

The resulting tapes became family treasures. When Elizabeth was a teenager, her adoptive parents presented her with the entire collection transferred onto cassettes and housed in a decorative box. It was her Christmas present.

She found respite in the classics, especially poetry. How much, one wonders, does literature owe worldwide to abusive parents and unhappy childhoods?

Worse was to follow. At 17 she was married to another pastor from her parents' church. It was soon apparent he was a pathological wife-abuser. He slapped her, kicked her, jumped on her stomach when she was pregnant, and on one occasion, after she'd pleaded for their dog to be allowed to spend the night in the house, made her sleep outside with it in the doghouse.

He called her disgusting. When they had sex he looked at pornographic pictures rather than at her. When once she went to kiss him, he slapped her face and said "Never try to do that again."

When her daughter was born, she lavished all her pent-up affection on the child, instinctively re-creating the loving relationship she had had with her own mother in Korea. Her husband responded by having sex with other women. On one occasion he made love to a hitch-hiker they had picked up on the back seat of the car. Elizabeth, having no choice but to continue driving, adjusted the rear-view mirror so that she didn't have to watch.

The pastor was an amateur photographer, and on one occasion was standing with his camera on the very edge of the Grand Canyon. Elizabeth tells how she was tempted to give him a sharp push, and was only prevented when her daughter, who she was carrying on her back, woke up. She didn't want to give her own child a traumatic memory of the kind she had grown up with.

When she decided to leave her husband, taking the child with her, her adopted parents were unexpectedly supportive. Adultery to them was a sin, and divorce because of it had Biblical justification.

The home she set up with the child was a re-creation of the one she had first known in Korea, frugal but full of fun, and in the lap of nature. She got a poorly-paid job as a reporter on a local newspaper, but at least was allowed to take her child in to work.

One night, however, a man she had been investigating turned up at her home when she was alone. The rape, and the subsequent abortion, must have seemed relatively minor events after the horrors that preceded them. They are certainly given little space in the narrative.

Gradually she progressed to better-paid jobs. Today she lives as a journalist and poet in the San Francisco Bay area, happy in the multicultural ambiance, and in the personal freedom she is able to enjoy.

Causes of abuse

What you learn from this book is that the abuse of women by men has many causes. Sometimes it's erotic pleasure in causing pain, sometimes the pleasure of exerting power, and sometimes the expression of a husband's frustration at the trap that marriage has caught him in.

"Honor killings" (considered as murders in all modern societies), and the intolerance of sexual "crimes," similarly appear to be products of a fear of freedom, and the unimaginable choices and responsibilities that would come with it.

This book sometimes appears plain and unanalytical, but this is actually its virtue and essential quality. Its candor is what makes for such an absorbing read.

Life, say the Buddhists, consists of 10,000 joys and 10,000 sorrows. It would appear that Ms Kim's portion of sorrow is by now complete. We can only hope her joys are only just beginning.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,