Fabric curtains stretch across the huge Warragamba Dam to trap ash and sediment expected to wash off wildfire-scorched slopes and into the reservoir that holds 80 percent of untreated drinking water for the greater Sydney area.

In Australia’s capital, Canberra, where a state of emergency was declared Jan. 31 because of an out-of-control forest fire to its south, authorities are hoping a new water treatment plant and other measures will prevent a repeat of water quality problems and disruption that followed deadly wildfires 17 years ago.

There has not yet been a major effect on drinking water systems in southeast Australia from the intense fires that have burned more than 104,000km2 since September last year, but authorities know from experience that the biggest risks are to come with repeated rains over many months or years, while the damaged watersheds, or catchment areas, recover.

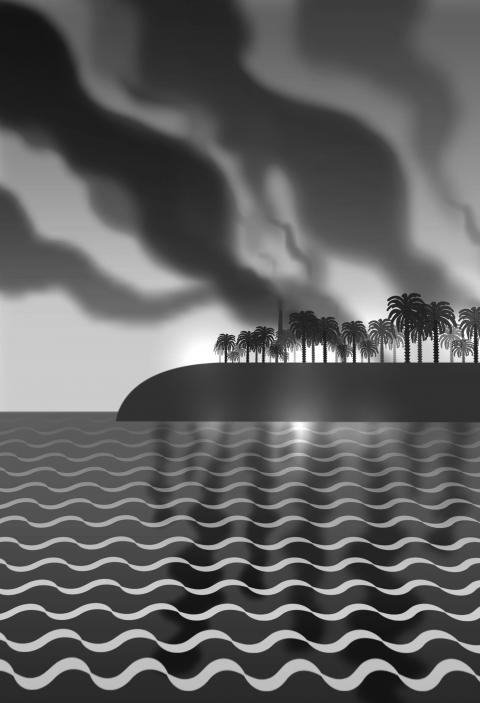

Illustration: Yusha

Due to the size and intensity of the fires, the potential effects are also not yet clear.

“The forest area burned in Australia within a single fire season is just staggering,” said Stefan Doerr, a professor at Swansea University in Wales who studies the effects of forest fires on sediment and ash runoff. “We haven’t seen anything like it in recorded history.”

The situation in Australia illustrates a growing global concern: Forests, grasslands and other areas that supply drinking water to hundreds of millions of people are increasingly vulnerable to fire due in large part to hotter, drier weather that has extended fire seasons, and more people moving into those areas, where they can accidentally set fires.

More than 60 percent of the water supply for the world’s 100 largest cities originates in fire-prone watersheds — and countless smaller communities also rely on surface water in vulnerable areas, researchers have said.

When rain does fall, it can be intense, dumping a lot of water in a short period of time, which can quickly erode denuded slopes and wash huge volumes of ash, sediment and debris into crucial waterways and reservoirs.

Besides reducing the amount of water available, the runoff can also introduce pollutants, as well as nutrients that create algae blooms.

What is more, the area that burns each year in many forest ecosystems has increased in the past few decades, and that expansion is likely to continue through the century because of a warmer climate, experts have said.

Most of the more than 64,000km2 that have burned in Victoria and New South Wales have been forest, including rainforests, scientists in New South Wales and the Victorian government have said.

Some believe that high temperatures, drought and more frequent fires might make it impossible for some areas to be fully restored.

Very hot fires burn organic matter and topsoil needed for trees and other vegetation to regenerate, leaving nothing to absorb water. The heat also can seal and harden the ground, causing water to run off quickly, carrying everything in its path.

That can clog streams, killing fish, plants and other aquatic life necessary for high-quality water before it reaches reservoirs.

Already, thunderstorms in southeast Australia in the past few weeks have caused debris flows and fish kills in some rivers, while fires continue to burn.

“You potentially get this feedback cycle,” where vegetation cannot recolonize an area, which intensifies erosion of any remaining soil, said Joel Sankey, research geologist for the US Geological Survey.

The role of climate change is often difficult to pin down in specific wildfires, University of Melbourne researcher Gary Sheridan said.

However, he said that the drying effects of wildfires — combined with hotter weather and less rainfall in much of Australia, even as more rain falls in the northern part of the country — mean that “we should expect more fires.”

Climate change has affected areas such as Alaska and northern Canada, where average annual temperatures have risen by about 2.2°C since the 1960s compared with 0.88°C globally.

As a result, the forested area burned annually has more than doubled over the past 20 to 30 years, Doerr said.

Although there might be fewer cities and towns in the path of runoff in those areas, problems do occur. In Canada’s Fort McMurray, Alberta, the cost of treating ash-tainted water in its drinking-water system increased dramatically after a 2016 wildfire.

In the western US, 65 percent of all surface water supplies originate in forested watersheds where the risk of wildfires is growing — including in the historically wet Pacific northwest.

By mid-century almost 90 percent of them are likely to experience an increase — doubling in some — in post-fire sedimentation that could affect drinking water supplies, a federally funded 2017 study found.

“The results are striking and alarming, but a lot of communities are working to address these issues,” Doerr said.

“It’s not all doom and gloom, because there are a lot of opportunities to reduce risks,” said Sankey, who helped lead the 2017 study.

Denver Water, which serves 1.4 million customers, discovered “the high cost of being reactive” after ash and sediment runoff from two large, high-intensity fires, in 1996 and 2002, clogged a reservoir that handles 80 percent of the water for its 1.4 million customers, said Christina Burri, a watershed scientist for the utility.

It spent about US$28 million to recover, mostly to dredge 765,555m3 of sediment from the reservoir.

Since then, the utility has spent tens of millions of US dollars more to protect the forests, partnering with the US Forest Service and others to protect the watershed and proactively battle future fires, including by clearing some trees and controlling vegetation in populated areas.

Utilities also can treat slopes with wood chips and other cover and install barriers to slow ash runoff. They purposely burn vegetation when fire danger is low to get rid of undergrowth.

Canberra’s water utility has built in redundancies in case of fire, such as collecting water from three watersheds instead of two, and it can switch among sources if necessary, said Kristy Wilson, a spokeswoman for Icon Water, which operates the system.

Water can be withdrawn from eight different levels within the largest dam to ensure the best-quality water, even if there is some sediment, she said.

That is paired with simpler measures, such as using straw bales, sediment traps and booms with curtains to control silt, and physically removing vegetation around reservoirs and in watersheds to reduce fire fuel, she said.

Eventually, some communities might need to switch their water sources because of fires and drought. Perth, on the western coast, has turned to groundwater and systems that treat saltwater because rainfall has decreased significantly since the early 1970s, Sheridan said.

However, for now, millions of people will continue to drink water that originates in increasingly fire-prone forests.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s